Author Henry Dee introduces his book, Militant Migrants: Clements Kadalie, the ICU and the Mass Movement of Black Workers in Southern Africa, 1896-1951, volume 21 in the Studies in Labour History book series published by the Society for the Study of Labour History with Liverpool University Press.

In the 1920s and 1930s, innumerable workers, as well as leading figures such as W.E.B. Du Bois, Tom Mann, George Padmore and Dorothy Woodman, all heralded Clements Kadalie as a phenomenon. He had achieved something impossible. Organising anywhere between 100,000-250,000 Black workers across Southern Africa into a single trade union, Kadalie won wage increases, improved working conditions and union recognition through a flurry of successful strikes and campaigns.

C.L.R. James projected Kadalie as a modern-day Toussaint Louverture. A. Philip Randolph’s newspaper, similarly, praised Kadalie’s trade union – the Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union of Africa (ICU) – for rapidly expanding after its 1919 formation into the ‘largest economic organization of black men in the world’.

By 1929, however, the ‘mother’ ICU had collapsed amid factional intrigue, endemic corruption and the dramatic rise of anti-immigrant sentiment across Southern Africa. Kadalie himself – originally a migrant worker from colonial Malawi – had become an alcoholic who deserted his wife and four kids, and left a generation of workers disillusioned. He remained a divisive figure for the rest of his life, denounced by moderate liberals and communist revolutionaries alike.

Despite his fame and notoriety, Militant Migrants is the first extended biography of Clements Kadalie. After arriving in Cape Town as a young, ambitious migrant in 1918, Kadalie quickly built the ICU into an organisation that transformed the political history of Southern Africa. Building on archival and oral history research in Britain, India, Malawi and South Africa, I make three main arguments over the course of the book. First, I rehabilitate the global significance of Kadalie’s ideas about class and migration, as part of a global moment when racialised workers throughout the world organised on a significant scale for the first time. Second, I demonstrate how the ICU organised as a border-crossing, all-in general trade union, and why this mattered amid the mass movement of materials, money and migrants across Southern Africa. Finally, I situate Kadalie among a heterogeneous generation of prominent Malawian migrants, who were at the forefront of wider social, religious and political change, but faced a wave of hostility at the end of the 1920s.

What were Clements Kadalie’s key ideas? Kadalie was always a propagandist rather than a theorist, emphasising deeds over words, but he was a pivotal figure in the remaking of class in 1920s Southern Africa. He is most famous as a trade union orator who regularly denigrated everyone at mass meetings, from the angel Gabriel to the prime minister of South Africa, James Hertzog – a hated ‘bugger’ who would lose access to his chamber pot if domestic workers went on strike. Kadalie’s rapid-fire speeches, nevertheless, also contained important political interventions. Despite the refusal of white governments and white trade unions to officially recognise Black labourers, the ICU instrumentalised the process of proletarianization to insist that their members were the ‘real workers’. Generating a significant body of radical literature, Kadalie and the ICU catalysed a new Black working-class identity through mass rallies, marches, speeches, essays, poetry, songs and artwork. And in doing so, they permanently changed debates, from whether Black workers could be organised, to how they should be unionised most effectively.

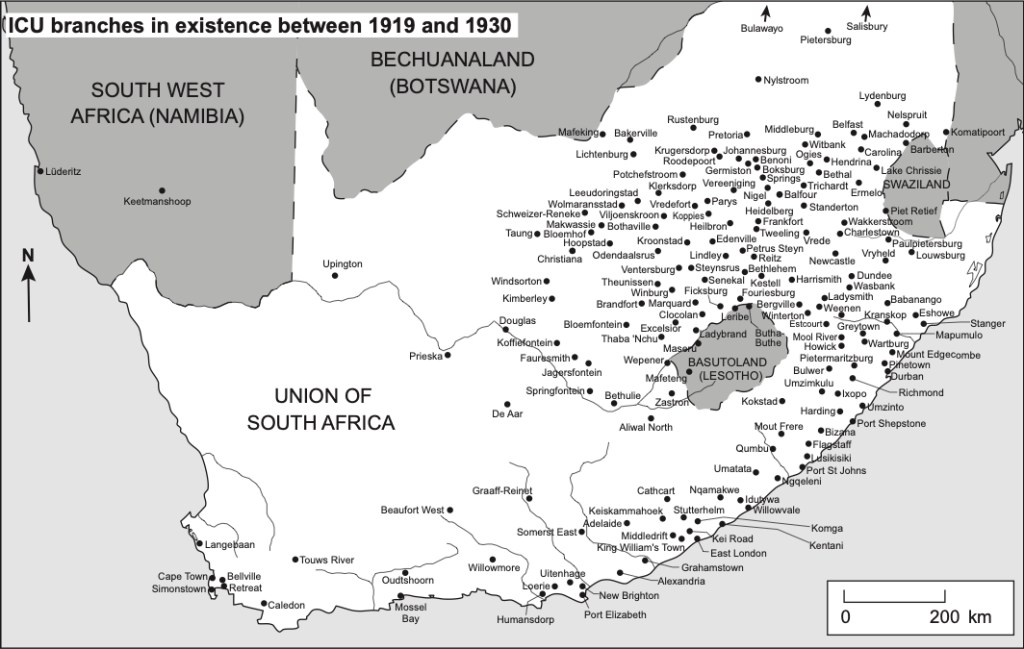

My second main argument is that the migrant background of ICU leaders and members has been similarly under-appreciated. The ICU is often invoked as an important precursor to the mass nationalist movements of the 1940s onwards in South Africa, Zimbabwe, Namibia and Malawi. But this interpretation belies the transnational reach of the earlier organisation, the transnational character of its leadership, and the fact that Kadalie himself insisted that the ICU was a trade union ‘first and last’. Reflecting extensive migrant labour networks that spanned the region, a host of ICU leaders (like Kadalie) were ‘foreign-born’ external migrants. James Gumbs, the ICU’s long-standing president, and George Deshon, an ICU executive leader, were both from St Vincent in the Caribbean. The ICU’s junior vice president, Emmanuel Johnson, was a factory worker from West Africa. Many other executive leaders were from Lesotho, Malawi, Zimbabwe and Zanzibar. In response to the proliferation of transnational migrant labour networks, the ICU prioritised organising across borders with small but significant branches in Namibia, Lesotho, Zimbabwe and Zambia. And, breaking with their African nationalist contemporaries, they fought against deportations and restrictions on mobility, regularly defending the free movement of all workers across Southern Africa.

My third contention is that Kadalie’s Malawian background is almost always mentioned but typically misunderstood. This mattered, not only because Malawians had a significant, unrecognised impact in early 20th South Africa, but because the backlash against them at the end of the 1920s was a key aspect in the ICU’s own undoing. Prominent as domestic workers and ballroom dancers, a striking number of Malawians stood at the head of millenarian working-class organisations in 1920s Southern Africa. J.R.A. Ankhoma, Kadalie’s own moderately inclined, Johannesburg-based uncle, for example, led one of the region’s first Pentecostal churches, as well as the first Malawian nationalist organisation anywhere on the Africa continent, the Nyasaland Native National Congress (NNNC). Malawian men, however, also faced widespread allegations of ‘stealing’ women and jobs, pointing to difficult questions around masculinity, family, and sexuality. Anti-Malawian riots hit Lichtenburg and Johannesburg in 1927. Speaking in the late 2010s, Rhoda and Winifred Kadalie, two of Kadalie’s granddaughters, were keen to rehabilitate memories of Kadalie’s wives, Molly and Eva, and their children, Alexander, Robert, Clementia, Fenner and Victor – their grandmothers, mothers and aunts, fathers and uncles and aunts – who suffered most from Kadalie’s alcoholism and adultery. Their experiences mattered not only in terms of understanding Kadalie’s personal development, but also in terms of the broader tensions that Kadalie and other Malawian men invoked. Indeed, by the early 1930s, an unprecedented moment, when hundreds of thousands of workers were led by militant migrants from across Africa and the Caribbean, had come to an end.

A key challenge for me throughout this project has been to reconcile Kadalie’s unprecedented successes with his inescapable failures. At the same time as he faced damning accusations of autocracy, conservatism and corruption, he also initiated new ways of organising, new vocabularies of worker militancy, and challenged other leaders – in Britain, America and Southern Africa – on their moderation and exclusionary nationalism. Today, in Southern Africa and beyond, governments and trade unions continually fail to redress stark economic inequalities, challenge global capitalist interests and oppose xenophobic violence. For all his failings, Kadalie’s life remains a compelling and necessary tale – of audacious ambition, inclusive solidarity and organised mass struggle.

Find out more about Militant Migrants and order a copy.

Find out more about the Studies in Labour History book series.

Find out more about the book launch, 29 November 2025.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.