Evan Smith offers a guide to the growing volume of left, labour and radical history resources now online, and introduces the directory of more than 500 collections to be found on his New Historical Express blog.

Digitisation is a major part of archival practice and historical research today. While it is not a substitute for archival research and only a small percentage of archival material around the world has been digitised, it nevertheless has broadened what is now available for historians and other researchers. Particularly when travel was restricted during the pandemic, digitised materials allowed historians to find more resources without making long journeys to the archives.

It is not just institutions, such as archives and libraries, that have been involved in digitising historical material. Community groups, political organisations and individual researchers, to name a few, have been conducting their own digitisation projects. Sites such as the Internet Archive have become important places for digitised material to be stored and made accessible to researchers. With many of these non-institutional digitisation projects, there has been an emphasis on open access so that anyone interested in reading historical primary sources can view them freely. Despite the limitations of digitisation, online and open access digital collections can be a way to democratise research by making it available to more people.

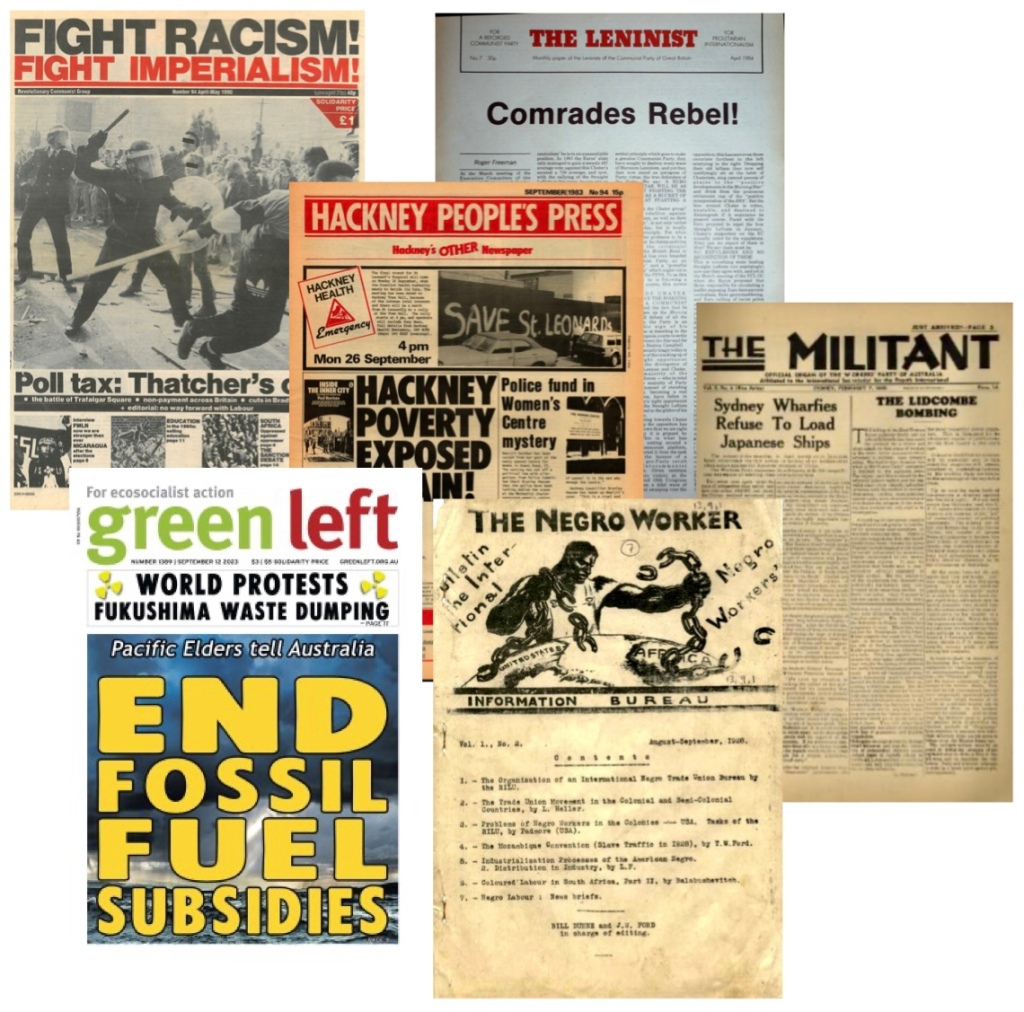

Activists have long been at the heart of digitising archival and historical sources for researchers around the world. For example, the Marxist Internet Archive has been making Marxist texts available online since the mid-1990s and over the past two decades, it has built up a massive collection of digitised left-wing newspapers, journals and pamphlets. This has been contributed to by individual activists as well as some institutions, such as the Tamiment Library in New York. Other examples of activists banding together to create digital collections of left-wing material include the Irish Left Archive, Splits and Fusions and the Sparrow’s Nest Anarchist Library, amongst many others.

There has been much enthusiasm on the left for the increased digitisation of radical, left-wing and labour historical material because it helps people understand the history of such movements, providing inspiration and lessons to take from defeat. Making radical historical material online and open access allows for many voices from below to be heard and challenge dominant narratives about past events and struggles. Through these digitisation projects, we can locate the thoughts and feelings of the trade unionist, the anarchist agitator, the anti-colonial rebel or the anti-war protestor, to name but a few.

Although it is worth mentioning that it is not just activists who are making these radical collections available online. In certain countries, national and state libraries have digitised left-wing newspapers, journals, pamphlets and other ephemera. For example, Trove, the online platform of the National Library of Australia, has digitised the various newspapers of the Communist Party of Australia from the 1920s to the 1990s, as well as the newspaper of the Australian section of the Industrial Workers of the World (Direct Action) and Australia’s first Trotskyist journal (The Militant).

Special collections at universities have also been instrumental in digitising and making available significant amounts of radical historical material. This tends to be reflected in the resources of universities in the Global North, with North American universities hosting extensive online collections of radical, left-wing and labour historical documents. These are not just confined to North American radical history, but these special collections hold material from around the world. Latin America in particular is well represented, with collections from across the region (here and here). The International Institute for Social History in Amsterdam is another repository with significant online collections of radical movements from many places, including Egypt, Lebanon and India.

This highlights an issue with the digitisation of archives more broadly. Institutions such as libraries, archives and universities in the Global North generally have more funding and infrastructure to support the digitising of archival and historical materials. Institutions in the Global South often do not have the same levels of support to make archival material available online, which creates a gap in whose histories are accessible by researchers and the wider public. But institutions in the Global South are digitising more and more material, including radical, left-wing and anti-colonial. For example, South Africa’s Digital Innovation South Africa collection has an extensive online collection of material relating to communism, trade unionism, Pan-Africanism and the Anti-Apartheid Movement.

***

As a precariously employed scholar in Australia, digitised collections offered a way to access historical materials far beyond what I could have hoped to examine in person, constrained by distance and time. Writing about transnational radicalism across the Anglophone world, I was able to access digitised material from Britain, Australia, South Africa, the United States, New Zealand, Ireland and Russia from my home in Adelaide and download extensive PDFs to analyse at my own pace. While I have been fortunate in the past to travel to different countries to conduct archival research, my current projects could not be completed without the help of digitised collections of radical historical documents.

There has been a steady increase in the number of radical online archives and collections available and in 2018, I started compiling a list to keep track of them for myself. Rather than just having them as bookmarks in my browser, I listed them in a spreadsheet in alphabetical order. As I was a regular blogger about various aspects of radical history and had posted about certain new collections in the past, I thought that other researchers (and left-wing trainspotters) would be interested in this list too. I started slowly adding to my list and eventually organised it by country or topic. In the past five years, my list of radical online collections has grown to over 500 different collections from around the world. You can visit my list here.

Some areas, such as Europe, North America, Australia and the Soviet Union, are very well represented in the list, while collections from Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America are typically less represented. This reflects the aforementioned discrepancies in support for digitising projects in the Global South, but as an Anglophone researcher, my knowledge of collections available on these regions is not as expansive. I rely heavily on suggestions from other researchers (usually via social media) and online translation tools to find suitable online collections from the non-Anglophone world. I welcome any suggestions for further collections to added, in any language and from anywhere in the world!

I think that the collection has struck a chord with people and it is by far the most visited page on my blog. People have told me that it has been a great help in locating material for their research or teaching (I have used it myself to teach how to read primary sources with undergraduate students). Some of the most visited collections from the list are The Negro Worker, the Marxist Internet Archive’s Listing of Trotskyist Periodicals and Journals, Sovetskoe Foto (Soviet photography journal), the SACP’s African Communist and the IISH’s League Against Imperialism archive.

With more than 500 collections listed in over 80 categories, my list of radical online collections is a gateway to a world of left-wing, labour, activist and anti-colonial history that was previously only available in libraries, archives and private collections. It is not a substitute for what is held in these institutions, but I hope that my list has made it easier for people to locate and access documents that illuminate the history of those who have struggled.

Evan Smith is a Lecturer in History at Flinders University in South Australia. He is also a Visiting Research Fellow with the University of Adelaide. He has published widely on radical history in Britain, Australia, Ireland and southern Africa. He blogs at New Historical Express and is on Twitter here.