Jack Taylor reports on his research into 1940s’ attitudes to empire in the Labour Party policy apparatus and among the leading Labour figures of the era.

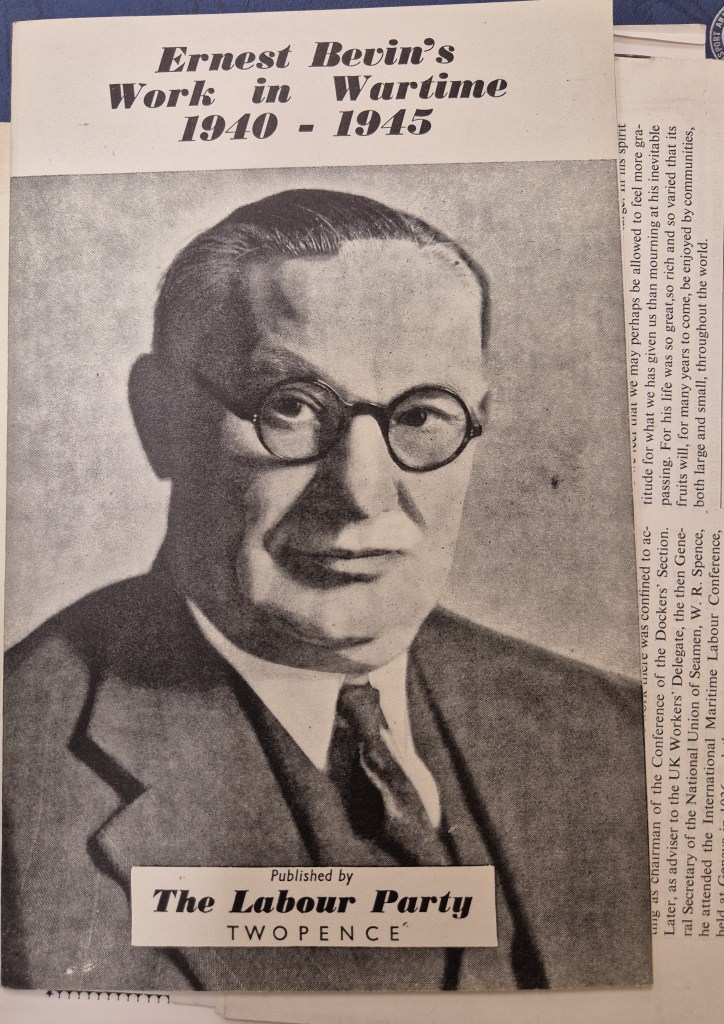

In researching the Labour Party’s post-war imperial policy in the Middle East, I became interested in ideas around British expertise and experience in shaping political institutions. A Society for the Study of Labour History research bursary allowed me to explore the development of Labour imperialism and to consider two interrelated questions. First: how did the party’s policy apparatus understand the empire and plan for its future during and after the Second World War? Second: how did Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin view the empire before taking office?

I began my research at the Labour History Archives to consider files related to Labour’s International Department and the plethora of foreign policy subcommittees that reported to the national executive committee. Of particular interest was mapping the evolution of thinking towards the empire and drawing a distinction between those outside the party, such as the Fabian Colonial Bureau, which ruminated on imperialism but were ultimately a step removed from power, and those who were able to wield it.

Fabian-inflected paternalism was writ large during the war years and was clearly expressed by the chair of the NEC’s international sub-committee, Hugh Dalton, who suggested that Labour’s priority in the colonies was to ensure the “well-being and education of the native inhabitants.” Crucially, Dalton also emphasised the importance of trusteeship in the “development of all natural resources” for the benefit of Britain and the colonies alike.[1] The desires of colonised peoples themselves were, unsurprisingly, a secondary consideration. Such was Labour’s belief in rational planning that the mass transportation of peoples between territories was considered, as were wide-ranging schemes to reshape representative political and social institutions along British lines.[2] In power, these would remain consistent themes.

While at the Labour History Archives, I was also able to spend time reviewing Denis Healey’s papers from his time as secretary of the party’s International Department. Under his stewardship, the department became an energetic source of anti-communist and anti-Soviet briefing materials and propaganda. Although Healey dealt primarily with European matters he kept one eye on the empire, identifying it as an ideological and economic battlefield that was both susceptible to Soviet influence and a source of much-needed revenue.

Importantly, Healey helped to formalise Labour’s foreign policy bureaucracy developing the International Department from a talking shop to a well-staffed department that collaborated closely with the Foreign and Colonial Offices and influenced policy debates through a slew of well-researched briefings and publications. Unlike the NEC’s International Sub-Committee or Advisory Committee on Imperial Questions, the department operated semi-autonomously with little scrutiny from representatives elected by the party’s conference.

My research subsequently moved to the Modern Records Centre where I considered papers connected to Ernest Bevin’s time as General Secretary of the Transport and General Workers’ Union (1922-1945). As leader of the United Kingdom’s largest trade union, Bevin’s prewar papers primarily concern domestic economic and social affairs. However, they also reflect an analysis of international policy based on two impulses. First, a strong belief in the necessity of effective world organisation to overcome the failures of the League of Nations and rationalise production.[3]Records detailing his attendance at the 1938 British Commonwealth Relations Conference in Australia illustrate Bevin’s vision for a more integrated empire as an imperial military and economic counterbalance to totalitarianism.[4]

Second, Bevin was convinced that the export of British social democracy – and trade unionism in particular – was essential to economic prosperity and peace. It was, Bevin argued, the labour movement’s responsibility to carry the empire “a stage further forward” economically and socially to raise living standards abroad and allow for the fruitful exploitation of resources.[5] Bevin’s approach was in some respects similar to that of the Fabian Colonial Bureau, however, rather than relying on bureaucratic expertise, he saw institution building as the most fundamental issue. It is possible to draw a line from this emerging philosophy and, for example, his efforts to cultivate the international labour movement through the formation of the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions in 1949.

A final note of interest was Bevin’s employment of specialist staff to finesse his vision, particularly John Price. A multilingual Ruskin scholar, Price headed the T&G’s combined Political, Research, Education, and International Department. His book The International Labour Movement (1945) reads like an outline of Bevinist internationalism, particularly in its forceful advocacy of the labour movement’s role in state and economic management.

Embarking on these trips has been highly stimulating even if I perhaps have more questions than answers. Regardless, I feel I am in a strong position to move into the next phase of my research.

Dr Jack Taylor is the author of Oil, Nationalism and British Policy in Iran: The End of Informal Empire, 1941-53 (Bloomsbury Academic, 2024). He is currently researching the Attlee Government, development and empire.

References

[1] International Post-War Settlement, 11 January 1944, Labour Party International Department Box 21/4 (LHA).

[2] CWW Greenidge, Mass Transfer of Populations, January 1945, Labour Party Advisory Committee on Imperial Questions Memorandums 1944-45; The Colonies and International Accountability, April 1945, Labour Party Advisory Committee on Imperial Questions Memorandums 1945 (LHA); Rita Hinden, ‘Colonial Trade Unions’, Socialist Commentary no. 3 (1945), 55-8.

[3] Speech to Sixth Biennial Delegates’ Conference of the Transport and General Workers’ Union, 9 July 1935, MSS.126/EB/X/4 (MRC); Ernest Bevin, ‘How to Stop War’, John Bull, 21 Sept 1935.

[4] Draft speech, undated (1938); My World Tour, undated (1938); Commonwealth Relations, 20 December 1938, MSS.126/EB/BC/20 (MRC)

[5] Peace or War? Full Report of the Momentous Debate at the Margate Trades Union Congress on the Present International Crisis (London: Trades Union Congress, 1935), 15.

Find out more about bursaries on offer from the Society for the Study of Labour History.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.