Factory magazines enabled independent researcher Lily Ford to uncover women’s experience in the aircraft factories of the First World War, with the help of an SSLH research bursary.

My research uncovers the women behind the scenes in British aviation. It offers a new view of the development of flight in Britain from the 1890s to the 1940s, and looks at areas where women were involved with the machinery of flight. The First World War represents one of these areas. More than 120,000 women were making aircraft components by 1918, a figure usually hidden within munitions manufacture data[1]. I have been investigating what life was like for these workers. A bursary from the SSLH this summer gave me the opportunity to travel to Manchester and Lincoln to look at material from aircraft manufacturers.

Soon after the outbreak of war, hundreds of factories around the country were converted or created to make aircraft components. Women workers had always been part of aircraft manufacture, notably in fabric, but with the rapid increase in demand for planes and male soldiers, their presence on shopfloors increased and spread to departments previously closed to them – metalwork, carpentry and assembly. Photographs and film clips held by the Imperial War Museum and other archives show that their presence in this newly expanded industry was well documented and publicised at the time.

I wanted to move beyond the frame to find out more about this phenomenon. Factory magazines provide an insight into the social and corporate life of their communities.

A tip from the AVRO historian Steve Abbott sent me to the Humphrey Verdon Roe collection held at the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester. Verdon Roe and his brother Alliott founded AVRO in 1910 in Brownsfield Mill, Manchester, and the museum’s collection includes a two-year run of their factory magazine, the Joy-Stick, from its founding in early 1917.

I examined the Joy-Stick with attention to the ways in which female employees were referenced and included. In its early days it was an organ for gossip, framed as ‘Things we want to know’, such as ‘If Miss —- knows that Mr —- is married?’. From the very first item there is a play on the tensions of a newly mixed workplace: [we want to know] ‘If the Ladies of a certain Department come down in any more shades of socks and blouses whether the lads of AVRO will be off bad with Trolley Boys’ Disease or in the Latin “Glimpsus Ankli and Veenecki”’[2]. This is a coy but straightforwardly sexist rhetorical move, blaming women and their choice of apparel for distracting men with their bodies[3]. However it’s possible to see a shift in the wartime life of the magazine towards a more inclusive culture for women.

Initially, whenever women are mentioned in these archly expressed questions, the focus is on the attraction between the male and female workers. A vein of banter runs through the publication with both men and women as the objects of humour, and while the joke is more often on the women, by September 1917 there are occasional female contributors of longer articles, and women winning writing competitions alongside men. In January 1918 the Joy-Stick published a series of visual puns supplied by staff, including a drawing from a female contributor called ‘The Trailing Edge’, where the technical term for the tapered back edge of a wing is given new meaning as a wardrobe malfunction. By taking the jargon of aircraft manufacture and relating it to her own body, this employee displays both an easy familiarity with her workplace and the confidence to comment on female clothing to a mixed readership. In March 1919, as AVRO would have been winding down their war operation and laying off their female employees, there were two articles about social occasions from a female perspective, again suggesting a high degree of cultural security for women workers.

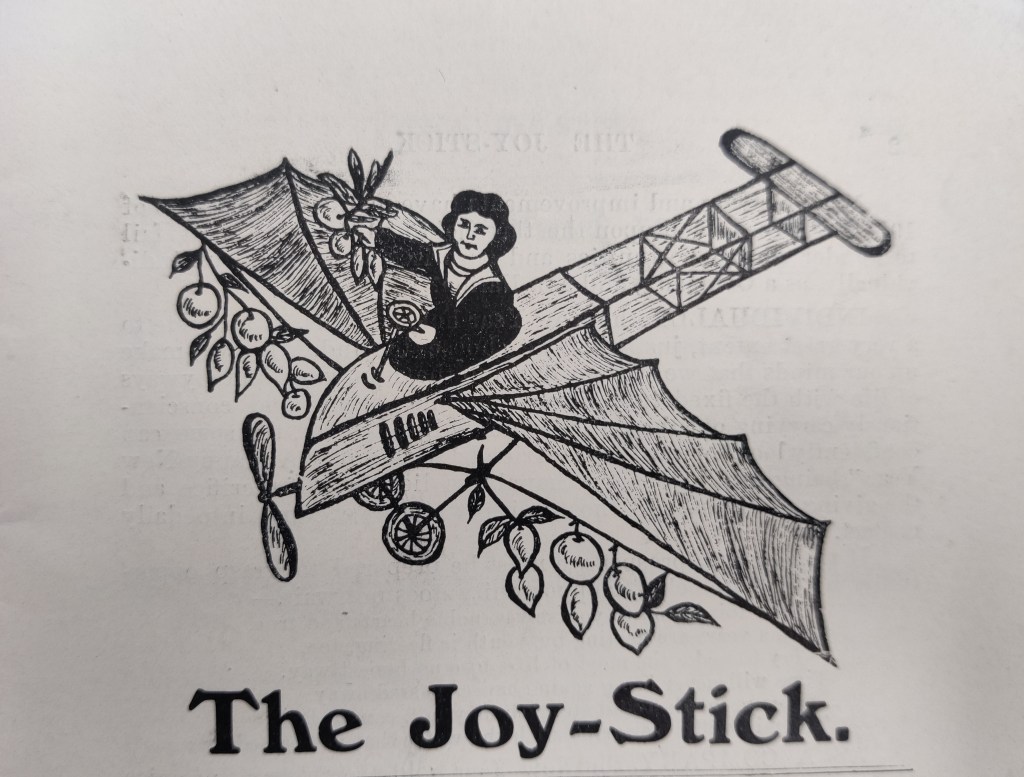

The glimpses of life for women employed making aircraft in this period are valuable because of the limitations of other evidence. According to my investigations with local and corporate archives, no employment records now exist for war workers in these factories. The magazines, with their whimsical and sometimes ribald references to women workers, at least occasionally reveal a name or a voice. Some publications mention female employees hoping for or being given ‘joy rides’, that is, a short flight as a passenger, evidence of a high degree of understanding and engagement with the technology they were engaged in making. An employee at Blackburn in Leeds wrote a thrilled account of her flight[4]. No joy rides are mentioned in the Joy-Stick, but for one month, in January 1918, its cover illustration changed from the habitual and rather phallic eponymous object to a rustic style print of a female worker flying solo. Her plane is adorned with festive fruits, as if to set some distance between the normal function of the warplane and the fantasy cornucopia that might issue forth in a world where women could take to the air.

These archival discoveries will help me to round out the picture of women working in aircraft production during the First World War. My objective was to put more granular detail to the imagery accessible through digitised visual archives such as that of the Imperial War Museum. The contextual information furnished by company papers, and magazines such as the Joy-Stick, brings texture and nuance to my investigation. Thanks to the SSLH for this opportunity.

[1] H.A. Jones The War in the Air Vol. VI, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1937, p. 85

[2] The Joy-Stick, 23rd Feb 1917, p. 1. Science and Industry Museum archives: A2010.85/Box3/13

[3] Employees often had to provide their own overalls and caps, a fact shown in the photographs and films online at the Imperial War Museum and other archives, and mentioned in A Munition Worker’s Career at Messrs. Gwynne’s, Chiswick, 1915-1919 by Joan Williams, 1919, Imperial War Museum Collection LBY 30096, p. 8.

[4] ‘A Girl’s First Flight’ The Olympian [Blackburn factory magazine], May 1917, 1:4, p. 8. National Aerospace Library, Farnborough.

Dr Lily Ford is an independent filmmaker and historian based in London. lilyfordresearch.com.

Find out more about bursaries on offer from the Society for the Study of Labour History.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.