My PhD thesis asks: when do trade unions come to support universal welfare policies? It pursues the question through a comparison of the British and American labour movements at the turn of the twentieth century.

Thanks to the funding from the Society for the Study of Labour History, I was able to make two archival visits which hugely advanced my research. The first was to the Modern Records Centre at the University of Warwick, where I examined the records of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants (ASRS)—including meeting reports and issues of Railway Review from 1875-1911. The second was to New York City, where I visited Columbia’s legal archives, fraternal society documents at the New York Public Library, and trade union records at NYU.

Throughout much of the nineteenth century, the British and American movements shared a common tradition of ‘bread and butter’ unionism which emphasized the integrity of the high-grade white male worker, rejecting socialist politics in favour of Victorian ideals like self-help, independence, and thrift. Integral to this model was a range of health, pension, and death benefits paid into by members on a recurrent basis. By end of the century, however, the official orientation of the two movements had radically diverged: while the British Trades Union Congress came to support universal state health and pension schemes, the American Federation of Labor made common cause with insurance providers to resist social insurance proposals advanced by reformers in the American Association for Labor Legislation.

My primary contribution is to argue for the importance of organizational environment in shaping the strategies undertaken by trade unions, and their broader political positioning. In the first section of my dissertation, I demonstrate how the trajectory of friendly and fraternal mutual benefit societies shaped trade union reasoning on welfare benefit provision.

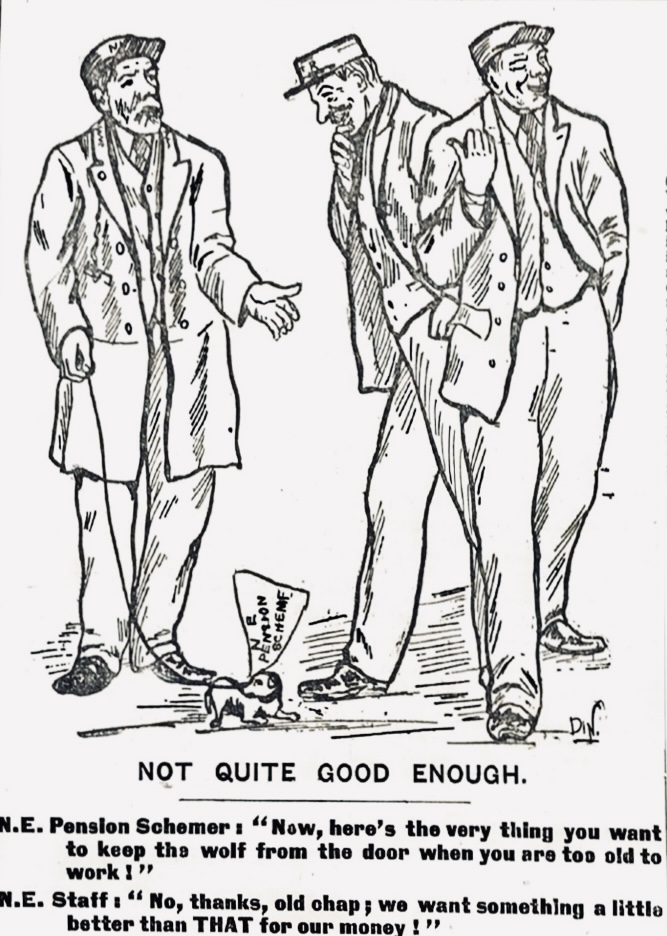

In my study of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers (ASE), the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants (ASRS), the Cigarmakers International Union (CMIU), and the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen (BLF), I came to understand that, early on, trade unions embraced benefits in order to legitimate trade unions in the eyes of elites within a hostile legal environment, and appeal to a public already familiar with benevolent organizations. Though prior research has pointed to the importance of the friendly and fraternal society form in shaping trade union development in each case, my archival work carefully exposes the importance of these societies for trade union reasoning throughout the period under consideration. Drawing on records from the Independent Order of Oddfellows and the National Fraternal Congress, I suggest that a crisis in the friendly society movement during the late nineteenth century, and a resulting decline in the popularity of the societies, significantly reduced the appeal of benefits as an organizing tool for British trade unions. By contrast, the explosion of fraternal societies in the late nineteenth century United States, widely referred to as the “Golden Age of Fraternalism,” rendered benefits a persistently useful organizational tool for trade unions in the US.

The archival work I conducted in New York deepened my understanding of the structural developments behind the trends. An expansive body of literature has demonstrated how the uniquely repressive trajectory of American labour law has constrained the organisational avenues of US trade unions. With the documents I’ve collected on this archival trip, I can now say that my own research builds on this literature through a consideration of organizational opportunities. Placing legislation on trade unions in dialogue with that on friendly and fraternal societies reveals how governing elites defined and redefined the boundaries of legitimate working-class organization throughout the nineteenth century. Though trade unions were nominally legalized in the US in 1842 with the Commonwealth vs. Hunts case, and while in the UK they were outside the law until the 1871 Trade Union Act, in practice trade unions in both countries were legitimate so long as they confined their efforts to mutual benefit provision. At the turn of the century, this consensus changed: while British trade unions were given the freedom to strike, American trade unions faced incessant injunctions under the Sherman Anti-trust Bill. At the same time, avenues for benefit provision for British trade unions were narrowed with the legalization of employer benefit schemes and increased regulation of benefit societies. By contrast, in both the arbitration system initiated with the Erdman Act of 1898 and rights outlined in the Clayton Bill of 1914, the position of American trade unions as benefit providers was protected and secured.

The documents I surveyed also suggested that the evolution of corporate law is a vital and grossly understudied force in shaping the political trajectory of trade unions. Between the Bubble Act of 1720 and the Limited Liability Act of 1855, the UK government was selective in the granting of corporate charters and promoted the formation of voluntary associations. In an effort to encourage ‘benign’ working class organization, the government designed a ‘quasi-corporate’ status for friendly societies which promised them the protection of corporations without the government interference which came with it. Trade unions in the UK were thus presented with three possible legal identities: corporation, quasi-corporation, and voluntary association. The leadership of the TUC, alongside liberal reformers, campaigned for the expansion of the quasi-corporate status granted as friendly societies to trade unions—giving them the right to act as a single entity without the legal responsibilities of one. In the US, incorporation was granted widely and freely as a means of stretching state power without enlarging the bureaucratic body of the state. Throughout much of the nineteenth century, fraternal benefit societies incorporated at the national level while trade unions were denied this possibility. Like their counterparts in the UK, reformers in the US campaigned for trade unions to be given equal status as fraternal benefit societies. But American trade union leaders were not willing to surrender to the regulation and legal liability of a corporate charter—positioning them against reformist groups. The question of incorporation thus crucially shaped the architecture of political debate around the identity and function of trade unions in this period, and the sort of alliances the two trade unions movements were able to form.

Maya Adereth is a PhD student at the London School of Economics. Her research focuses on Class Formation through an Organizational Lens: Friendly Societies, Trade Unions, and Universal Welfare in the US and UK at the Turn of the 20th Century.

Find out more about bursaries on offer from the Society for the Study of Labour History.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.