Untold thousands of trade union emblems were produced in the Victorian era, but by the twentieth century they looked out of date and their use was in decline. Mark Crail looks at a 1930s revival that briefly breathed new life into the genre.

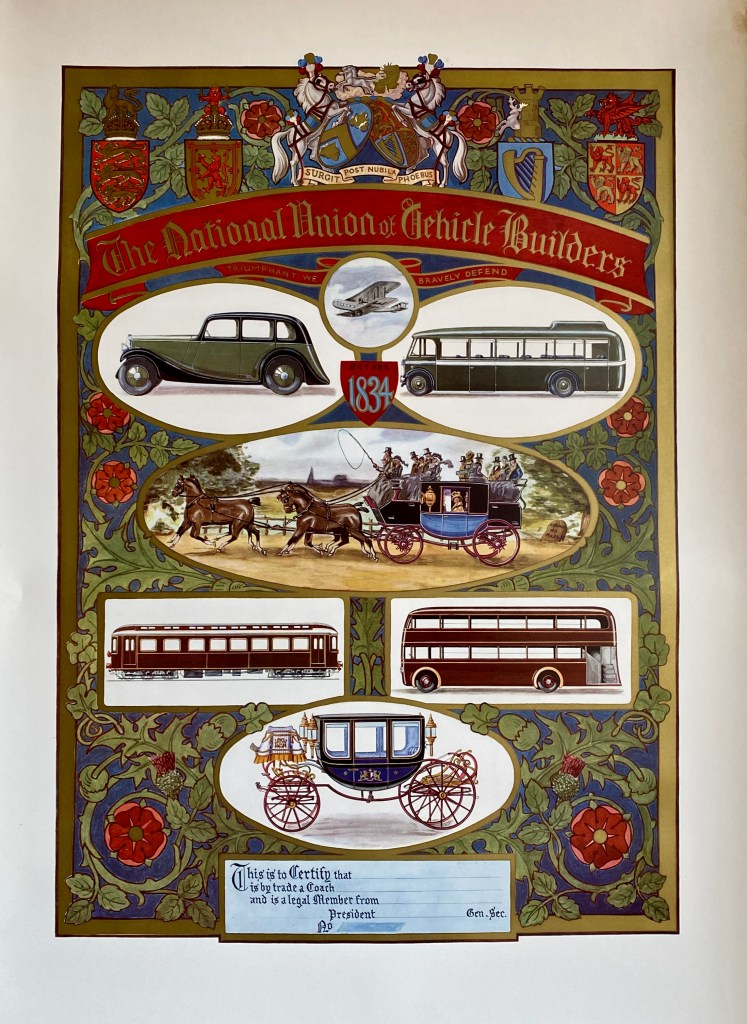

The trade union membership certificate shown here (Fig. 1) was based on an emblem adopted in the 1930s by the National Union of Vehicle Builders. In an era of rapid technological advance, the union’s members were at the heart of a transport manufacturing industry which had moved on in the course of a single working lifetime from constructing horse-drawn carriages to mass-manufacturing cars and passenger airlines.

Now, by putting the planes, trains and automobiles of this new machine age at the centre of its union emblem, the NUVB was updating an artefact of trade union identity that had looked increasingly out of date.

The trade union emblems that formed the centrepiece of so many unions’ membership certificates had had their heyday in the final thirty years of the nineteenth century. Emerging in an era when classical imagery held cultural sway, they more often than not were dominated by temple-like ‘architectural settings’ in which pagan deities and Christian saints featured alongside union members working at their trades.

Certificates such as those produced by the Amalgamated Society of Engineers and the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners (Fig. 2) at the start of the period, and the Amalgamated Society of Tailors (Fig. 3) towards its end were colourful, frequently stuffed full of symbolism and typically more complex than the same unions’ banners – which needed to be easily recognised from afar.1

And for decades they genuinely were an important part of union life. Arthur Pugh, the first general secretary of the Iron and Steel Trades Confederation, wrote in his history of the union that, ‘The emblem was a great feature of trade union membership in those days [the 1890s] and there were few active members of the union who did not adorn his home with an emblem certifying the date of his entry into the union, signed by the general secretary and mounted in a suitable frame.’2

They served a practical purpose too. F. W. Galton, who was secretary to Sidney and Beatrice Webb and provided them with ‘a graphic description of union life’ for their History of Trade Unionism, explained that a union member would often buy a union emblem to hang in the front parlour at the time of his marriage. ‘To him it is some slight connecting link with the other men in his trade and Society. To his wife it is the charter of their rights in case of sickness, want of work, or death. As such it is an object of pride in the household, pointed out with due impressiveness to friends and casual visitors.’3 The friendly society role of trade unions was crucial in this period.

But times changed. When the state began to take an increasing role in social welfare, such certificates became less important to members. And by the 1920s they were more difficult to produce. As Robert Leeson, author of the first study of trade union emblems put it: ‘With the great wave of amalgamations after the First World War, the style and title of many old unions disappeared and the new unions were too big for emblem issues, preferring the more popular badges. For a while the Amalgamated Society of Woodworkers over-printed the old Carpenters’ emblem, but as a general rule their use was as awards to long-service members.’4

But this was far from being the end of the story for the trade union membership certificate, and the 1930s seem to have witnessed not just a small-scale revival of union emblems but an abandonment of the classical school of design in favour of a modern look and feel that openly celebrated the power and glory of the machines manufactured and operated by union members.

The mid-1930s’ emblem of the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen is perhaps the epitome of this new look. But the train drivers were not alone. Arthur Pugh’s own Iron and Steel Trades Confederation, which only came into being in 1917, adopted an emblem that included no fewer than eleven images showing their members at work in modern-day settings, though these vignettes were still contained within what appeared to be an architectural structure, albeit one of iron or steel.

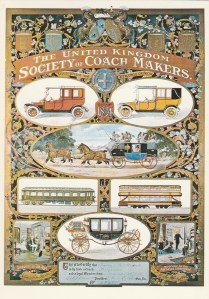

The United Kingdom Society of Coachmakers, meanwhile, had already produced an emblem in the early years of the twentieth century that showed its willingness to abandon the muses, saints and symbolic arches favoured by its Victorian forebears, incorporating the cars and trams that its members were making (Fig. 4). The overall look, however, remained busy and crowded. By the 1930s, and now renamed the National Union of Vehicle Builders, it was ready to do it all again. Although the Latin and English mottos and heraldic shields were retained, the union simplified the floral backdrop to its design, stripped out all reference to an outmoded friendly society role, and brought in pictures of the newer vehicles now being built by their members – including for the first time a plane.

The NUVB had a long history by the time this version of the emblem appeared. Founded in 1834 as the United Kingdom Society of Coachmakers, it had 5,000 members by 1860, and affiliated to the TUC in 1872 and the Labour Party in 1906. In 1919, it merged with rival unions to form the NUVB, hitting a membership of 26,000 in 1925. As the labour historian Dave Lyddon has noted: ‘The rise of the motor industry, far from destroying coachmaking unionism, wrenched it out of a long period of stagnation.’5

It is possible that the new design was adopted to mark the union’s centenary in 1934 as the emblem appears to show identifiable if slightly simplified vehicles of the correct period. The aircraft may be based on a Handley Page Hannibal, the largest airliner in the world when it was introduced in 1931; and the car is almost certainly a Daimler 15, a model which entered production in 1932.

The NUVB, however, was not necessarily well equipped to benefit from the rise of mass-manufactured cars. Although jobs in the motor industry multiplied, some of the union’s members’ skills rapidly became outmoded and redundant. Even as it was modernising its public image, in the early 1930s the union lost one-third of its members and, says Lyddon, ‘when an “Industrial Section” was created in 1931, it was a response to the union’s financial crisis caused by unemployment payments, and no serious recruitment of mass production operatives took place’. It would eventually become part of the Transport and General Workers Union in 1972.6

The revival of the trade union membership certificate was a short-lived phenomenon. Like the head office building boom of the same era, it effectively came to an end in 1939, but it did live on in lesser form, with new emblems commissioned in the post-war era as presentation pieces for long-serving members and those deserving of special recognition. A fine example of one such certificate, produced by the Transport and General Workers Union in the 1970s, can be seen in Fig 5.

Mark Crail is web and social media editor for the Society for the Study of Labour History.

Sources and further reading

1. The Art and Ideology of the Trade Union Emblem 1850-1925 by Annie Ravenhill-Johnson, edited by Paula James, 2013, London: Anthem Press.

2. Men of Steel: A Chronicle of Fifty-Eight Years of Trade Unionism by Arthur Pugh, 1951, London, Iron and Steel Trades Confederation.

3. History of Trade Unionism, by Sidney and Beatrice Webb (New Edition: Eighth Thousand), 1907, London: Longmans.

4. United We Stand: An Illustrated Account of Trade Union Emblems by R.A. Leeson, 1971, Bath: Adams & Dart.

5. ‘Craft unionism and industrial change : a study of the National Union of Vehicle Builders until 1939’ by Dave Lyddon, PhD thesis, University of Warwick, 1987. Accessed at https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.383643 (13 February, 2023).

6. Historical Directory of Trade Unions, Volume 2 by Arthur Marsh and Victoria Ryan, 1984, Aldershot: Gower.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.