With the Labour Party on the verge of forming its first government, one of the country’s most glamorous aristocrats decided to offer her childhood home to the party as a ‘Labour Chequers’. Mark Crail looks at what happened next.

Liverpool Street Station would have been a hubbub of activity on the afternoon of Friday, 23 March 1923. But as commuters hurried for their rush-hour trains home amid the noise and smoke of the LNER locomotives, the sight of senior station officials shepherding a small group of men and women across the forecourt to a waiting first-class Pullman carriage caused many to stop and stare.

Platform staff speculated that they might be a football team on their way to a weekend match. But as one newspaper reported the following day, ‘their chagrin can be better imagined than described when the explanation came that the travellers were not a football party but members of a political party of no less importance than the leaders of the Government Opposition’1.

The group, which included the future Home Secretary Arthur Henderson, Beatrice and Sidney Webb, and Charles Ammon, secretary of the Union of Post Office Workers, eschewed the luxury of the Pullman coach and insisted instead on ‘the modest accommodation of third-class carriages, two of which were specially set apart for their use’.

It would not be a long journey. The high-level Labour delegation was on its way to Easton Lodge, a rambling Victorian Gothic stately home near Great Dunmow in Essex, where it would be joined by the Labour leader James Ramsay MacDonald, John Clynes, who had led the party through its successful 1922 election campaign, and Frank Hodges, general secretary of the Miners Federation of Great Britain, all of whom arrived later by car.

Easton Lodge had been the childhood home of the aristocratic Frances ‘Daisy’ Maynard and later became the venue for high society soirées and assignations. Daisy, as its owner was always known, was nothing if not well connected. In 1881, aged twenty, she had married Francis Greville, heir to an earldom, and in due course she became the Countess of Warwick; she was also for many years the confidante and mistress of the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, and the inspiration for the song ‘Daisy, Daisy’.

But Daisy Greville was from a young age also a serial philanthropist, and a generous benefactor of charitable causes. Under the influence first of the radical journalist W. T. Stead and later of the Clarion editor Robert Blatchford, she was introduced to socialist ideas, and in November 1904 joined the Social Democratic Federation. As the ‘Red Countess’, she appointed socialist clergymen to Essex livings of which she was patron, and supported strikes involving the London dockers (1912) and Essex agricultural labourers (1914). After the first world war, she joined the Labour Party2.

Now the countess wanted to hand over Easton Lodge to the Labour Party to use as a venue for ‘weekend gatherings, for informal discussion and private conferences and for consultations with international delegates’, as the Yorkshire Factory Times reported3. The Labour contingent that travelled to Essex that March for a weekend house-party were there to assess the venue. The Factory Times report added helpfully, ‘Educational conferences and study circles will probably be arranged, and Labour Members of Parliament will find a convenient retreat near to London where they may retire for rest and recreation.’ The Lodge, and the idea behind it were instantly dubbed a ‘Labour Chequers’.

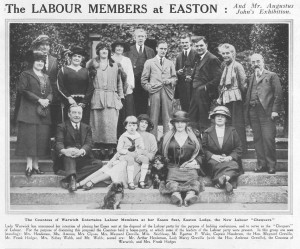

The delegation were impressed. On the Saturday evening, they were entertained to dinner by the Countess and her daughter, Lady Mercy Greville. They walked as a group through the fine gardens and admired the mature woodlands that formed part of the estate. In the warmth of the spring sunshine, Arthur Henderson and Frank Hodges took to the tennis courts in their shirt-sleeves. The author H. G. Wells, who lived nearby in a cottage provided by the Countess, joined the party and entertained them to dinner on the Sunday evening. And both press photographers and newsreel cameras were given access to capture the day (see below). The Labour contingent returned to London ‘delighted’ by what they had seen and eager to accept the offer.

At the end of June that year, the Labour Party held its annual conference in London, and a first opportunity arose to make use of Easton Lodge. At the end of the conference, delegates and visitors descended on Liverpool Street where three special trains were laid on to carry 1,000 people into Essex. As many again arrived at the Lodge by car and charabanc for a weekend fete and gala like nothing the Labour Party had seen before.

The local Essex Chronicle reported: ‘In large marquees erected at the back of the mansion, luncheons and teas were served to the visitors, the company being so large that it was impossible for all to get inside the marquees, so they sat about in hundreds in newly cut grass, and enjoyed their meals al fresco. Upon the lawn in front of the lodge tennis and bowls were played, and in the Park athletic sports took place. It was quite a rural gala, amid ideal surroundings. There was a very pretty exhibition by the Letchworth Folk Song Dancers, and general dancing followed. In the evening the Countess of Warwick distributed the prizes won in the sports at the cricket pavilion, and an open air meeting followed.’4

Thanked by Egerton P. Wake, Labour’s National Agent, for her kindness and generosity, the Countess apologised for the state of the sports ground, which before the war had been the second best of its kind in the county. For the past seven years, she said, it had been without a groundsman. ‘If anyone would volunteer to be groundsman for a year, she would offer a house and garden, and by next summer they would have the place in order for the Labour sports.’

Easton Lodge continued to play host to Labour events – though on nothing like the same scale as the summer fete. The new Socialist International met there in late July, replacing the old Second International that had collapsed in 1916 and in opposition to the Moscow-led Comintern. The left newspaper Justice, once the mouthpiece of Henry Hyndman’s Social Democratic Federation and now linked to a much smaller group of the same name inside the Labour Party, reported that those present had included Leon Blum from France, Adolf Braun from Germany, and Louis Pierard from Belgium. Henderson and Tom Shaw, the Lancashire weavers’ union leader who would become secretary of the new body, represented the British Labour Party. But Mussolini’s government refused to issue the Italian delegates with passports, and they were unable to take part5.

The Lodge would go on to be the venue in 1930 for early meetings of G. D. H. Cole’s guild socialist Society for Socialist Inquiry and Propaganda and in the spring of 1931 for the New Fabian Research Bureau. Plans to convert it into a permanent home for Labour events, however, never came to pass. As the Dictionary of Labour Biography notes: ‘At various times the Labour Party, the ILP and the TUC were involved, but in the end all the projected schemes fell through.’ The potentially ruinous cost of running the estate may well have played a part, and the difficulty in finding a groundsman may also have served as a warning: in the post-war era, you couldn’t get the staff.

Within a year of that first weekend house-party, MacDonald, Henderson and others had formed the first Labour government. The Red Countess contested Warwick and Leamington for the Labour Party in the 1923 general election, but came third behind the Tory and Liberal candidates, after which she gradually stepped back from public speaking ‘and other strenuous political activities’ to focus on writing; she died aged 77 in July 1938. When war came again, Easton Lodge was requisitioned by the War Office, and 10,000 trees chopped down to provide runways for the United States Air Force.

Unwanted and prohibitively expensive to restore and maintain, much of the house was demolished in the 1950s after being handed back to the countess’s descendants. The air force is long gone, but Stanstead Airport less than a mile away now provides the sight and sound of a different type of aircraft. And it is possible to visit the restored gardens created for the countess in 1902 and to walk in the footsteps of those 1930s politicians6. There is even a cafe called Daisy’s.

Mark Crail is web and social media editor for the Society for the Study of Labour History.

Sources and further reading

1. ‘Station Comedy. Labour Leaders Mistaken for a Football Team’, Nottingham Journal, Saturday, 24 March 1923 p.1.

2. ‘Warwick, Frances Evelyn (Daisy), Countess of (1861-1938)’ by Margaret Blunden, Margaret ‘Espinasse and John Saville in Dictionary of Labour Biography volume 5, London: Macmillan, 1975.

3. ‘Labour’s Country Home: Easton Lodge’, Yorkshire Factory Times, 5 April 1923 p.4.

4. ‘Labour at the Lodge. Lady Warwick’s 2,000 Guests. Rural Policy to be Formulated’, The Essex Chronicle, Friday, 6 July 1923 p.2.

5. ‘The New International’, Justice, Thursday 2 August 1923 p.1.

6. The Forgotten Gardens of Easton Lodge.

Daisy: The Lives and Loves of the Countess of Warwick, by Sushila Anand (London: Piatkus Books, 2008).