Delegates to the TUC’s annual congresses have been sent home with a commemorative badge for well over a century. But, as Mark Crail reports, these small souvenirs often carry a message about how the trade union movement sees itself.

The Trades Union Congress has produced a badge for delegates to its annual Congress since the very end of the nineteenth century. The practice continues today in an apparently unbroken run. But while this year-in, year-out routine speaks of continuity and tradition, changes in design over the decades say much about the TUC’s evolving view of itself and the messages it wants to send to the world. It also conceals something of the challenges that officials have faced in ensuring everything ran smoothly in the face of often overwhelming difficulties.

The earliest delegates’ badge to be found in the People’s History Museum’s collection, probably the most comprehensive in existence, dates from 1899, and although it is thought that the Amalgamated Society of Engineers may have produced a badge for its own delegates to Congress as early as 1893, the plain metallic 1899 design showing clasped-hands within a five-pointed star produced for that year’s gathering at Plymouth was the first to have been given out to all delegates.

1899-1908: the first ten years

There seems to have been no question that this innovation would continue, and at Huddersfield in 1900, delegates received a badge featuring the host town’s civic arms in its centre, a feature of many of the designs that would follow in the decades to come. There was also text setting out the year and location, and a motto. In 1900, this had read, ‘Labor [sic] conquers all things’, though by the following year, when Congress met in Swansea, it had been rendered into Latin as ‘Labor omnia vincit’.

The first official mention of a delegates’ badge came in 1904, when that year’s TUC Report noted that, ‘The Reception Committee presented each of the delegates with a most attractive badge as a souvenir of Congress. Additional badges may be had by applying to Mr O. Connellan, 4, Carlton Mount, Leeds.’ At this stage, responsibility appears to have rested with the local trades council – which would also have organised many of the social events that surrounded the week-long event.

The badge was certainly attractive. For the first time, it featured coloured enamels on a gold background, with text embossed into the metal badge – a step up in quality from the early printed badges, and a foretaste of things to come.

During these early years, however, there was little consistency in the design year to year as local reception committees went their own way. When the TUC convened in the Potteries town of Stoke on Trent in 1905, the badge was made of porcelain. But by 1906, a fairly standard look had begun to emerge, and this approach clearly proved popular – even though the specific design chosen lasted only for four years before being replaced.

1909-1925: workers by hand and by brain

In 1909, the TUC adopted a new design: at the centre was a red enamel heart within which, picked out in gold, were a crossed shovel and pick, overlaid with a pen nib representing the ‘workers by hand and by brain’ who would later feature in the Labour Party’s 1918 constitution. The heart itself was set against a map of the world centred on the Greenwich meridian with the word ‘Labour’ beneath it. And round the edge, in a circle, ran the words ‘Trade Union Congress. D.J. Shackleton MP chairman 1909 Ipswich’ in gold lettering on red enamel.

It would seem that by this stage (and perhaps as early as 1906), the TUC had relieved local reception committees of responsibility for the badge. Summary accounts published in the TUC Report that year included an entry for ‘Badges for Congress … £34 19s 2d’.

One delegate, H.H. Elvin of the National Union of Clerks queried the cost, however, and apparently with access to more detailed accounts ‘desired some information with respect to the £21 spent upon the Labour badge’. The TUC Report notes that W.C. Steadman (parliamentary secretary to the TUC) had replied that, ‘The money down for the Labour badge represents the purchase of the design and the cost of the die, which is now our absolute property.’

This seems to have been a sound investment. The die was used every year without fail between 1909 and 1925, successive badges differentiated by changes in the colour of the enamel and in the encircling text as Congress moved on to Sheffield, Manchester, Derby, Newport, Newcastle, Hull, Blackpool, Derby and Scarborough.

In 1924, however, the organisers had to make a late change: Margaret Bondfield, who would have been the first woman president of the TUC, had stood aside after becoming instead the first woman Cabinet Minister in the short-lived Labour minority government, and the name of Alf Purcell had to be substituted. The TUC would not elect another woman to the role until 1943, when Ann Loughlin, later to be general secretary of the National Union of Tailors and Garment Workers, took office.

1926-1933: hands around the world

Delegates to the 1926 Congress in Bournemouth can hardly have been in celebratory mood. Four months after the defeat of the General Strike, and with miners in some parts of the country still locked out, the ‘Parliament of the Labour Movement’ chose not to debate the dispute or to allude to it in anything but the most general terms as ‘the crisis in the mining industry’. So the decision to roll out a brand new design was most likely in keeping with wish to talk about other things.

The design adopted that year was more ornate than anything that had gone before. A circular pendant hung from a golden scroll on two hoops. More internationalist in tone and with echoes of the work of Walter Crane, it shows idealised male and female workers clasping hands across a globe. A sash with the word ‘Labour’ circles the globe, and the words ‘Trades Union Congress’ appear below it. The new design had added a final ‘s’ to the word ‘trade’. As in previous years, the outer circle was used to record the year, the name of the chair, and the host town or city.

Although this new design would be reused until 1934, with changes to text and coloured enamels, there were subtle changes to the central image. In 1931, a biplane was added at the top of the picture, balancing the ship that had been there from the start. And the male and female figures adopted slightly different poses. It looks very much as though a different die was created each year.

1934-1945: from the Toldpuddle Martyrs to war shortages

In 1934, Congress convened in Weymouth to mark the centenary of the Tolpuddle Martyrs’ arrest and transportation to Australia. The TUC had organised a competition seeking a commemorative design, and the winning image proved to be immensely popular. Although the general shape and structure of that year’s TUC badge remained unchanged, the ‘Farewell to convicts’ image gave it a fresh look and feel, and would be reused in future years in other formats.

Then, after a brief return in 1935 to something resembling the badges of 1926-1933, someone decided that a new approach was needed.

The badge rolled out for the 1936 Congress in Plymouth retained the pendant structure of its predecessor but restored the civic coat of arms of the host town or city to the design, and replaced the imagery of earlier badges with the letters ‘TUC’. This may have been a bold statement by an organisation that had regained its self-confidence after a difficult decade, but it lacked much of what had made those earlier badges so attractive.

The design was retained into the early war years, when shortages of metal and manufacturing capacity eventually made it impossible to produce badges of the same quality, and a cheaper printed tin badge was issued instead. When in 1945 the miners’ leader Ebby Edwards took the chair for the second year running (in place of George Isaacs, who had been appointed Minister of Labour), it proved impossible to present him with the traditional gold president’s badge. Instead, Ann Loughlin promised that a gold bar to mark his second term would be added ‘when gold is again available’.

1948-1987: postwar conformity

By the late 1940s, with shortages easing, the TUC abandoned the old pendant in favour of a single piece of metal, but otherwise left the design unchanged. Like its pre-war predecessor, the new badge had a coloured enamel circle at its centre with the letters ‘TUC’ picked out in white. A further circle of white enamel ran round it, and featured the president’s name, the venue and the year of the event.

With only the text and the colour of the enamel changing from year to year, this new design was in use until its final outing in 1971, with just one exception: in 1968, the text in the centre of the circle read ‘TUC 100’ and the coat of arms was replaced with a scroll reading ‘CENTENARY’.

What came next was equally standardised. The traditional circular badge gave way in 1972 to a lozenge, based on the design first used for a one-off additional centenary badge three years earlier. The name of the president and the venue continued to run in a band around the outside of the badge, with ‘TUC’ and the year in a central area of a different colour.

The one incident that may have affected the tranquillity of badge production during these years came when Danny McGarvey of the boilermakers’ union died during his term of office. Marie Patterson, who had already served as president in 1975, was persuaded to return, and saw out the remainder of McGarvey’s term of office, becoming, in 1977, one of a tiny number of people to have overseen two congresses.

Although the badges produced during this time were the most unimaginative of all the designs used over the years, they did evolve little by little, with variations in font and increased use of contrasting colours of enamel adding some variation during the 1980s. But for a brief re-use of the ‘Farewell to convicts’ image to mark the 150th anniversary of Tolpuddle in 1984, the TUC lozenge would hold sway until the end of the 1980s.

1988 to date: the age of the slogan

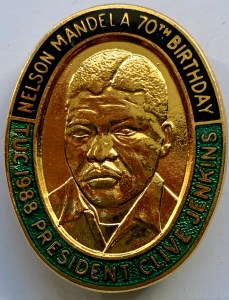

When Clive Jenkins became TUC president in 1988, he wanted something different to commemorate his year in office. Keith Faulkner, then the TUC’s in-house designer was asked to liaise with Jenkins’ office to come up with something new and achievable, and the result was the stunning green, black and gold badge marking the seventieth birthday of Nelson Mandela. Faulkner, later senior events officer for the TUC, retained responsibility for the delegates’ badge until his early death in 2010, and helped to usher in something of a golden age of TUC badge design.

In 2008, he told the Trade Union Badge Collectors’ Society how he went about it: ‘The normal process these days is that the president is asked what overall approach is desired, and previous examples and basic layout approaches provided for their consideration. Once an approach/theme has been decided, further layouts are developed until such time as the president is happy. The badge manufacturer – currently the very excellent Badges Plus of Birmingham – then takes the basic black and white artwork and uses this to make the mould from which the basic badge is made, and then in-fills any colour and adds an appropriate “pin”.’

There has been no ‘standard’ design since the groundbreaking Mandela badge of 1988, as incoming presidents have opted for badges in a kaleidoscope of coloured enamels, different shapes and, since 2003, an annual slogan. These have varied from the one word ‘Respect’ (1996) to the aspirational ‘Make poverty history’ (2005) and ‘Changing the world of work for good’ (2017), and Bill Morris’ still resonant ‘Respect for asylum seekers’ (2001). In effect, what was a ‘corporate’ TUC badge has been transformed into a TUC president’s badge.

The most recent enforced change to the design of delegate’s badges, however, came in 2020 with the advent of covid. While previous badges had named the host town or city, both the 2020 and 2021 congresses were held online – so there was no venue to add. This approach was also adopted in 2022, although in the event, and after an unforeseen postponement, congress returned to one of its more regular venues, Brighton.

Mark Crail is web and social media editor for the Society for the Study of Labour History.

Further information

- TUC Congress badges in the People’s History Museum form part of a larger collection of union badges. We are grateful to the People’s History Museum for permission to reproduce photographs of TUC badges for the years 1899, 1900, 1904, 1907 and 1934.

- TUC Congress badges held by the TUC Library are catalogued as part of the library’s special format collections

- ‘Farewell to convicts’: the long life of a classic trade union image on this site (20 February, 2022)

- Interview with Keith Faulkner on the Trade Union Badge Collectors Society (4 November, 2008)

- The Badges Plus YouTube channel has a series of series of videos showing the badge manufacturing process. Badges Plus made many recent TUC Congress badges.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.