In our continuing series on places in labour history, Joe Stanley draws on his family’s history to recall the pit pony races that raised money and the morale of Rotherham miners during the 1926 general strike.

In 1997, my great uncle Denis Stanley (1920-2011) published a history of his childhood in Brinsworth, Rotherham, in the Ivanhoe Review, a journal of local history in his home town. Rotherham Main Colliery, where all our family worked, featured prominently in his article. In it he stated that ‘Coal, and those who gave their lives to produce it, are now part of these spoil heaps, and I only hope that history will be kinder to them, than ever was John Brown and Co.’[1] This labour history place will explore Canklow meadows, a few hundred yards from the colliery gates, where in 1926 at the height of the lockout, miners and their families gathered for pit pony races, to raise funds and to bolster support for the Yorkshire Miners’ Association.

The miners’ lockout began on 30 April 1926. The president of the Cadeby Main branch in Doncaster spoke for many Yorkshire miners when he commented, ‘We might as well starve at home as work and starve’.[2] On 4 May the rest of the British workers joined the miners in a General Strike. One and a half million workers in Yorkshire stood with the miners. In Sheffield and Rotherham, the iron and steel industries were virtually idle.[3] On 12 May the TUC called off the general strike: an unconditional surrender to the government.[4] The miners, subsequently, fought their battle alone.

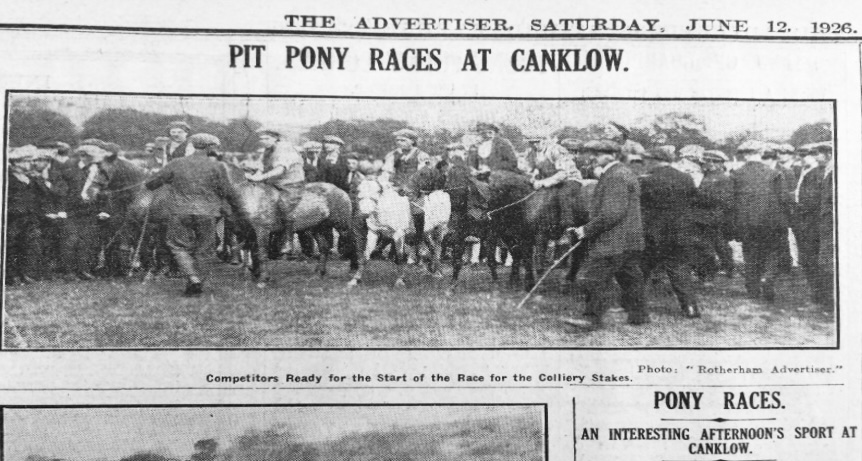

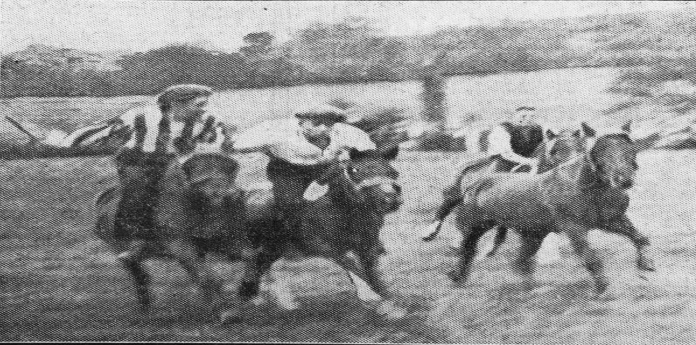

Many miners, at first, enjoyed being out of the pit. My great auntie Audrey, who was born in 1927 and still lives Brinsworth, recalls how her father Joseph Pick reminisced about the warm weather and how well the vegetables grew on the allotment. In June, the Rotherham Main YMA branches organised the pit pony races in Canklow meadows, part of the grounds of Howarth Hall.[5] Food vouchers were given away as prizes by the Rotherham Main sports committee. A crowd of 5,000 turned up to watch the event and the collection taken on entrance amounted to £8 16s. 4d.

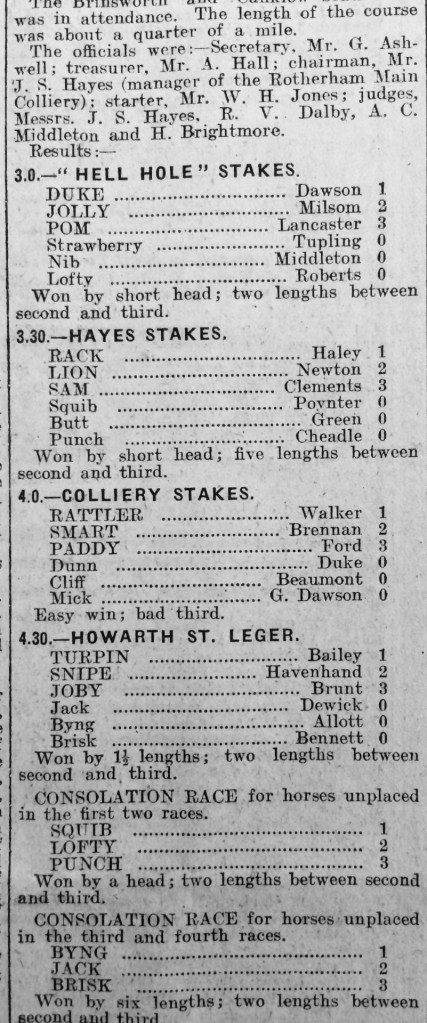

There was a total of six races and the Brinsworth and Canklow brass band played throughout the event. The first race, ran at 3.30pm, was the Hell Hole Stakes, and this was won by the pony Duke, read by Mr Dawson. (The Hell Hole was a part of Whiston and Canklow meadows). The second race was the Hayes Stakes, which was won by Rack, ridden by Haley. The third race, the Colliery Stakes, was won by Rattler ridden by Walker, and the fourth race, the Howarth St. Ledger was won by Turpin ridden by Bailey. In the two following consolation races, Squib won the third, and Byng the fourth.[6]

Below are some photographs of the races.

As the strike progressed the Nottinghamshire miners, let by George Spencer, found themselves in a position to negotiate a district settlement and, foreshadowing what happened in 1984, returned to work and formed a separate union. The following day Spencer was brought before the Federation and justified his actions with pride. The Yorkshire miners’ leaders were incandescent and Spencer, along with other Nottinghamshire miners’ leaders, were denounced across the coalfield. Herbert Smith told Spencer that he ‘would rather be shot in the morning than do what you have done’.[7] Joseph Jones, originally a Thurcroft official declared that he would ‘rather his body be mutilated and dead than he would recommend or admit to a reduction in wages or an increase in hours’.[8] Spencer was expelled from the Miners’ Federation. At the beginning of November 44,000 out of 51,000 were back at work in Nottinghamshire. In Yorkshire, only 30,169 had returned out of the 180,000 miners in the coalfield. And, according to Robert Neville, 12,000 of these were strikebreakers who had come into the West Riding from other counties to obtain employment which had been offered to Yorkshire miners and turned down.[9] The support for the strike in Brinsworth and Canklow was relatively solid but towards the end some men did go back.

The dispute formally ended on 30 November 1926, and was an utter defeat for the miners; subsequently, hours were increased and wages reduced. The pit pony races on Canklow Meadows provide us with a ‘worms eye view’, in the words of Christopher Hill, to understand how Yorkshire miners raised funds to sustain the lockout amid rising poverty and distress in the Yorkshire coalfield.[10]

[1] D.C. Stanley, ‘The Wooden Hill: Life in Brinsworth’ in Ivanhoe Review: Bulletin of the Archives and Local Studies Section Central Library Rotherham No. 9 (1997), p. 33.

[2] R.G. Neville, The Yorkshire Miners 1881-1926: A Study in Labour and Social History. Unpublished University of Leeds PhD Thesis (1974), pp. 698-699.

[3] Ibid., pp. 699, 705.

[4] Ibid., pp. 712-713.

[5] Howarth Hall was demolished to make way for the A630 linking Rotherham to Sheffield. My grandfather, who was born in Whiston in 1930, told me that when the house was demolished they found a body of a Civil War soldier behind the fireplace. I don’t know if there was any truth in it.

[6] Rotherham Advertiser, 12 June 1926.

[7] Neville, The Yorkshire Miners, p. 734.

[8] Ibid., pp. 719-720

[9] Ibid., p. 753.

[10] C. Hill, The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas in the English Revolution (London, 1991ed.), p. 14.

Read more articles in the series ‘A Place in Labour History’.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.