Gavin McCann is researching a book on trade unions and education. Here he writes about his visit to the South Wales Miners’ Library in search of a lost culture of socialist education.

‘I was in a second-hand bookshop in Cambridge — it would have been 73-74 — and came across two volumes of the history of the mining industry. I thought, bloody hell, where has this come from? I looked inside and saw they came from Trecynon miners’ library. I realised that these thieving bastards had gone to libraries like Trecynon and just taken these amazing volumes. Stolen!’

Ex South Wales miner

My visit to the South Wales Miners’ Library marked the final stop in the research journey for my book, Libraries Gave Us Power: A History of Trade Unions and Education, due to be published in February 2027. Thanks to the support of the Society for the Study of Labour History I was able to make the trip and spend valuable time with the records.

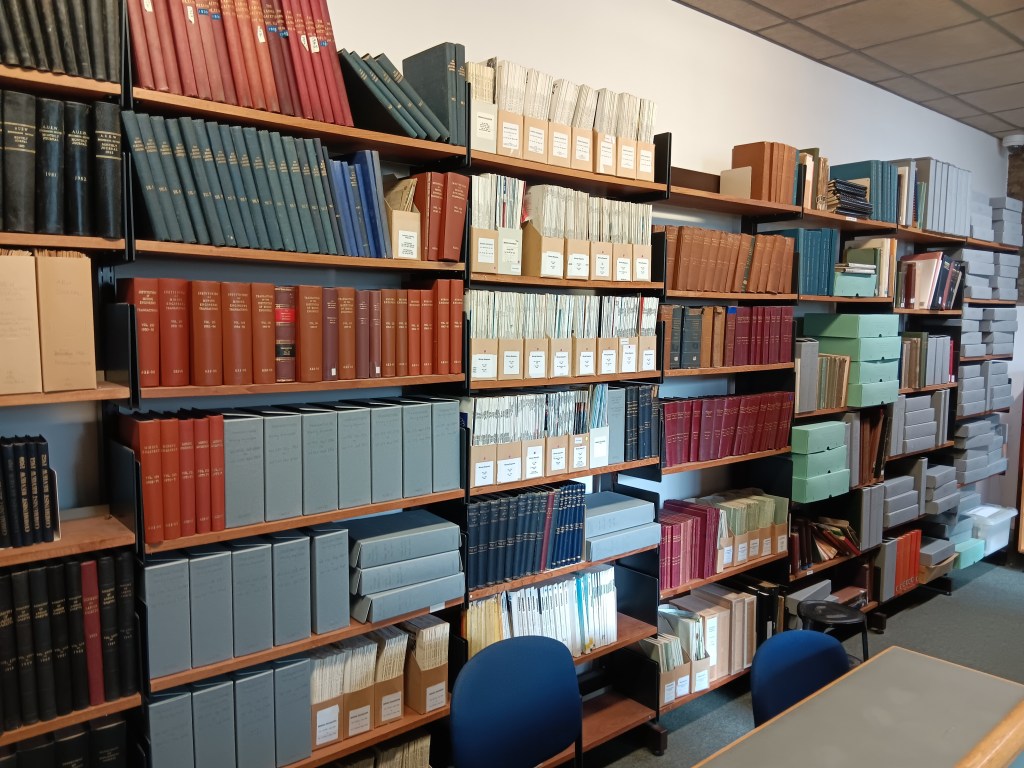

I had long held a hazy sense that something special had taken place in the coalfields of South Wales — a culture that cherished learning, even in the face of hardship. But it was not until I spoke with a former miner that the full depth of this legacy became apparent and I knew my research would not be complete without a trip to the South Wales Miners’ Library. Founded in 1973 amid growing concern that the miners’ libraries that dotted the coalfield were vanishing — along with their records, literature and spirit — the aim of the project to establish the Miners’ Library was to record what was in existence and bring it together under one roof.

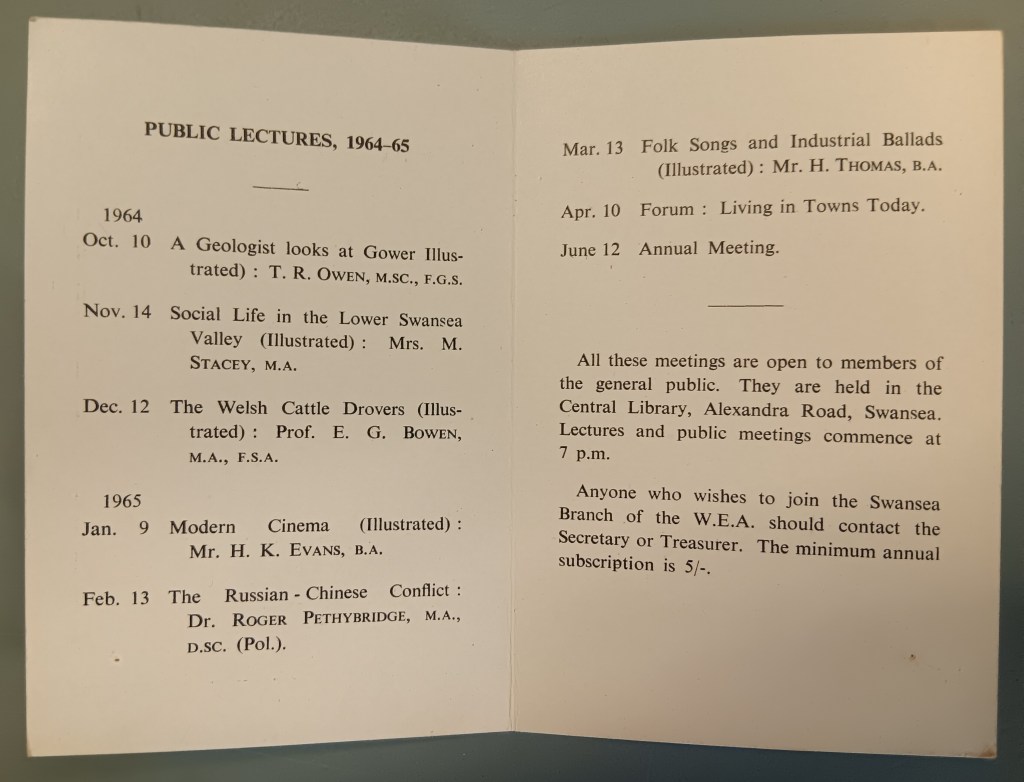

My focus was to try and understand how the autodidact culture and trade unionism were intertwined, and to further investigate the Workers’ Educational Association in Wales and the impact of the Central Labour College (CLC).

Among the most valuable treasures held at the Miners’ Library are the hours of oral histories, recorded by the project — interviews with miners, union leaders and local politicians. One key voice is James Griffith MP, who speaks of winning a scholarship to the CLC in London. On returning home, he became chairman of the lodge and went on to run four Labour College courses in nearby villages, teaching industrial history. His experience of the CLC is incredibly illuminating. He describes the Labour College as having ‘very considerably’ influenced the South Wales miners. He recalls Noah Ablett as ‘the ablest of that generation’, who returned and helped write The Miners’ Next Step, a critical document. That spirit of activism surged, culminating in the General Strike of 1926. But, as Griffiths reflects, after that, ‘all our energies were exhausted’ and in the aftermath the miners withdrew funding from the CLC.

Alongside the recordings, the item that had the greatest impact on my research was the Final Report of the South Wales Coalfield History Project, from 1974. This remarkable tome doesn’t just catalogue a collection — it captures a world on the brink of disappearing. The report lays out the project’s aims, details what was found, and, just as crucially, what had already been lost. It makes it clear that the closure of collieries meant more than the end of employment — it marked the erosion of a rich cultural heritage. Each village and town was made up of choirs, chapels, miners’ institutes, union lodges, and more.

Among the most striking sections are the inventories of personal collections, which offer intimate glimpses into the intellectual lives of working miners. One such entry — spanning thirteen pages — documents the archive of H.W. Currie, a miner at Abercynon Colliery. His collection includes books, pamphlets, NCLC certificates, and personal items, each one a thread in the wider story of working-class education and aspiration.

Nearly all of these items had been paid for by the miners themselves. A penny a week, usually deducted from their wages, funded the libraries. By the late 1930s, there were probably more than one hundred Miners’ Institute Libraries in the South Wales coalfield. The largest of them was at Tredegar, which spent £300 a year on books — with £60 set aside just for philosophy. This, I found, was managed by the library committee whose chairman was Aneurin Bevan, who also created his own ‘Query Club’ at the Institute to discuss politics and literature.

As the mines closed, so did the contributions from the miners’ wages to their local communities. The libraries fell into disrepair, the books sold on cheaply. Of all the things I read and heard, perhaps the most telling was the note that Hewlett Johnson’s Socialist Sixth of the World (a Left Book Club edition) was the ‘most frequently read in the Tylorstown Welfare Library: over thirty times in one year, its normal red-orange cover being almost black with use’. In today’s world, the idea of a political book being worn down by use, rather than neglect, seems almost unimaginable — yet it speaks volumes about community and solidarity, and just how libraries gave us power.

I would like to express my gratitude to the extremely kind and supportive staff at the South Wales Miners’ Library who went out of their way to help, despite the huge move they were going through.

Find out more about bursaries on offer from the Society for the Study of Labour History.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.