John Clare (1793-1864) is considered England’s greatest working class poet. Greatly admired for his poetry and prose on the natural world, its joys and its losses, he has become an icon for the environmental movement. But in a new selection by Mike Mecham, a member of the Society for the Study of Labour History’s EC and chair of the John Clare Society, the poet is revealed as having a much wider gaze.

Through a labour history lens the selection focuses on the people who inhabited Clare’s world and the events that shaped them. Not just those in his rural and literary communities, but beyond to the powerholders, the powerless, outsiders and the victims of war. What they reveal are not only Clare’s sense of joy but his fatalism and his empathy for those of his class and others often worse off than himself. It was an empathy mixed with anger and contempt for some power holders closer to home.

While the collection details rural relationships and customs, along with witty reflections on the London literary community, a section on the ‘Powerful and the Powerless’ addresses war and its consequences. Clare’s powerful manuscript ‘O Cruel War’ speaks from the perspective of a woman left behind by a soldier; and ‘The Wounded Soldier’, an early Clare poem, with its cry for peace – ‘O sheath, O sheath thy bloody blade in peace’ – still speaks to us today. As he says in ‘The Soldier’s Grave’, ‘His love was to his country true / His fate is wept by the morning dew.’

A recurring theme for Clare is ‘Honesty’ where, as he says in another poem, ‘the rich man claims it’ and often ‘buys its substitute.’ In the powerful ‘Labourers Hymn’, a longer poem, he calls on reformers to challenge the ‘tyrant’ and ‘knave’ who ‘while they raved for liberty forged chains for all the world.’ Whatever his own predicament, he still sees that there are others worse off than himself, such as the African beggar he comes across in London.

Everywhere he calls out the sufferings of the least powerful: an orphan begging on the streets and those dying of hunger, ‘for wants of bread’.

Clare empathised with outsiders and outcasts because in many respects he was one of them, especially when spending the last twenty-three years of his life in an asylum where he continued to write hundreds of poems, many included in the book. The gypsies, who Clare regularly fraternised with, were historic outsiders and Clare’s reference, in a prose extract recounting the call for their ‘extermination’ by a local magistrate, shocks the modern reader.

He also writes sympathetically about another group of history’s outsiders, the Jews. While his poem ‘Freedom’ was inspired after reading about the plight of Spanish war refugees in London. There is also empathy for the Irish emigrant in an early poem. Despite all his toil and hardships in an alien land the emigrant knows that it will never be enough to get him home. Clare paints a picture familiar to generations of Irish families.

John Clare draws the reader into his world through the power of his language as well as offering a mirror to our own. Collectively they represent an example of history from below, showing Clare as an acute social commentator and critic. As he says in one of his later poems: ‘I gave my name immortal birth / And kept my spirit with the free’.

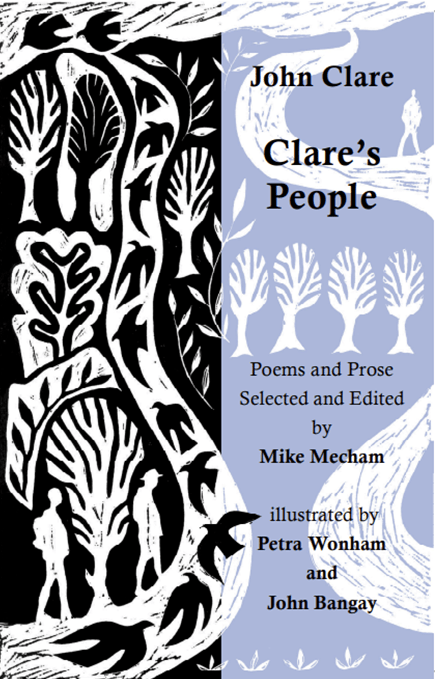

Clare’s People is published by the John Clare Society, price £12, and can be ordered post free from the Society’s Sales Officer. Click to order.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.