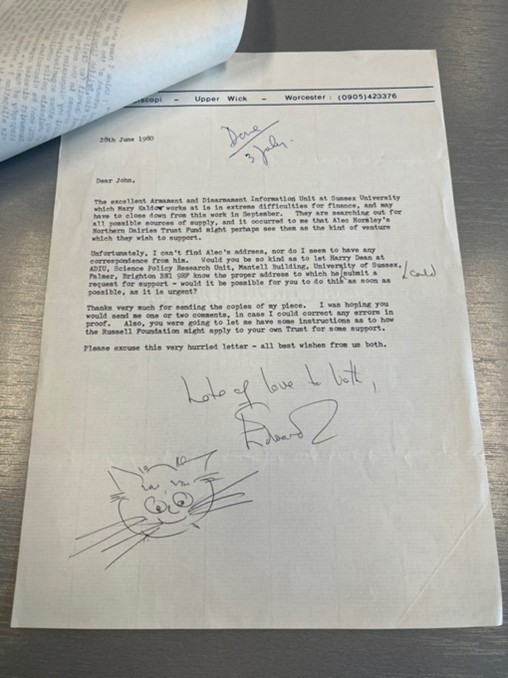

It is one thing to read E. P. Thompson’s published, polished texts; it is quite another to handle the papers he once worked on, to see the rust left by paper clips, the gum pressed between pages, the coffee stains on letterheads, and the quirky cat he drew (surely the same cat he invoked in The Poverty of Theory, where he wrote with characteristic scorn, ‘I have asked my cat.’) [see figure 1] in a letter to an old comrade.

I am deeply grateful to the Society for the Study of Labour History for the research bursary, which enabled me to engage more closely with E. P. Thompson, to develop an empathetic understanding of him, not just as a scholar and political critic but as a person. This sense of affectionate proximity, balanced by the critical distance required of historical inquiry, lies at the core of my PhD project. My research explores how historical distance is configured in politically engaged historiography, through a comparative reading of three anglophone historians: Howard Zinn, E. P. Thompson, and Natalie Zemon Davis.

During this archival trip, I set out to trace how The Making of the English Working Class emerged from Thompson’s politically engaged work, as an adult education tutor and as a central figure in the British political movement that would later become known as the New Left. However, there is currently no consolidated collection of Thompson’s papers accessible to researchers. Correspondence from his wife, the historian Dorothy Thompson, indicates that after E. P.’s death, she donated the bulk of their papers to the Bodleian Library in Oxford, where Thompson’s father’s archive is also held. This collection, however, will remain closed to the public until 2043. As a result, my research led me to the Hull History Centre, where I consulted the papers of John Saville, Thompson’s long-time collaborator from 1956 onward, and to the archives of the Department of Extra-Mural Studies at the University of Leeds [see figure 2], where Thompson taught between 1948 and 1965.

It is important to acknowledge the archival availability, as it has produced a partially fragmented view of Thompson’s legacy. Studies that draw on the records at Leeds focus narrowly on Thompson’s role as a teacher. Those based on the John Saville Papers portray him primarily as a polemicist. Meanwhile, the vast majority of scholarship on Thompson, especially on him as a historian, relies on no archival sources at all.

This is particularly regrettable, because when consulted together, the archives reveal that The Making was deeply rooted in Thompson’s politicised daily work. The book took shape as much in the classroom, along the bumpy roads of the West Riding, and within the New Left movement, as it did in Thompson’s study and during hurried visits to the British Museum and local archives. Moreover, an unexpected and valuable discovery emerged during my research in Workers’ Educational Association Records: class reports written by Thompson between 1955 and 1964, long thought to have been lost (LUA/DEP/076/3/1). This was a pivotal period during which he was working on The Making. These reports suggest a far more intricate intellectual relationship between his teaching, classroom dynamics, and the book’s development than is typically acknowledged.

Taken together, these archival materials make it clear that Thompson cannot be meaningfully separated into distinct personas. His work, whether as educator, polemicist, or historian, was part of a single intellectual struggle: an unremitting commitment to socialist humanism, grounded in the affirmation of human agency and the belief that structural oppression could be challenged and overcome.

In the classroom, Thompson sought to disrupt the dominance of abstract university theory by grounding teaching in students’ lived experience and political engagement. He resisted imposing conventional ‘university standards’ drawn from the ivory tower—standards that privileged detachment and objectivity—on progressive adult learners (LUA/DEP/076/3/2). His pedagogical approach insisted on the value of experience as a site of knowledge, positioning education itself as a space where agency could challenge structural norms.

This same impulse animated his vision for The New Reasoner. On a morning in April 1957, still in his dressing gown, he shared his excitement with John Saville: ‘I am SICK (excuse me) of bloody great generalizations about this and that and the other, what we MUST do, what is CORRECT, and so on. I am interested in people, and their values, and the intelligent and informed discussion of particular things, arising from personal experience or the knowledge of facts’ (U DJS/1/62) [see figure 3, where this letter is archived]. His rejection of dogma in favour of particularity and lived knowledge was another expression of his broader intellectual commitment to human agency.

In both the classroom and the editorial project, we see Thompson grappling with the tension between individual experience and institutional constraint, between agency and structure. It is this very tension that lies at the heart of The Making’s central argument: that the process of class formation ‘owes as much to agency as to conditioning’.

Thanks again to the Society for the Study of Labour History, for making it possible to return, once more, to the question of why, as Perry Anderson once put it, each of Thompson’s historical works was ‘in its own way a militant intervention in the present, as well as a professional recovery of the past’. This time, however, the answer does not lie in the abstract and theoretical formulations of Arguments within English Marxism, an approach Thompson himself famously despised and rejected. With the necessary historical distance from that 1970s debate, and drawing instead on the textures of his own lived experiences and commitments as traced in the archives, I hope this answer might have met with his approval.

Bowen Ran is working on his PhD project titled ‘Distanciation and Approximation in Politically Engaged Western Historiography’ at Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Find out more about bursaries on offer from the Society for the Study of Labour History.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.