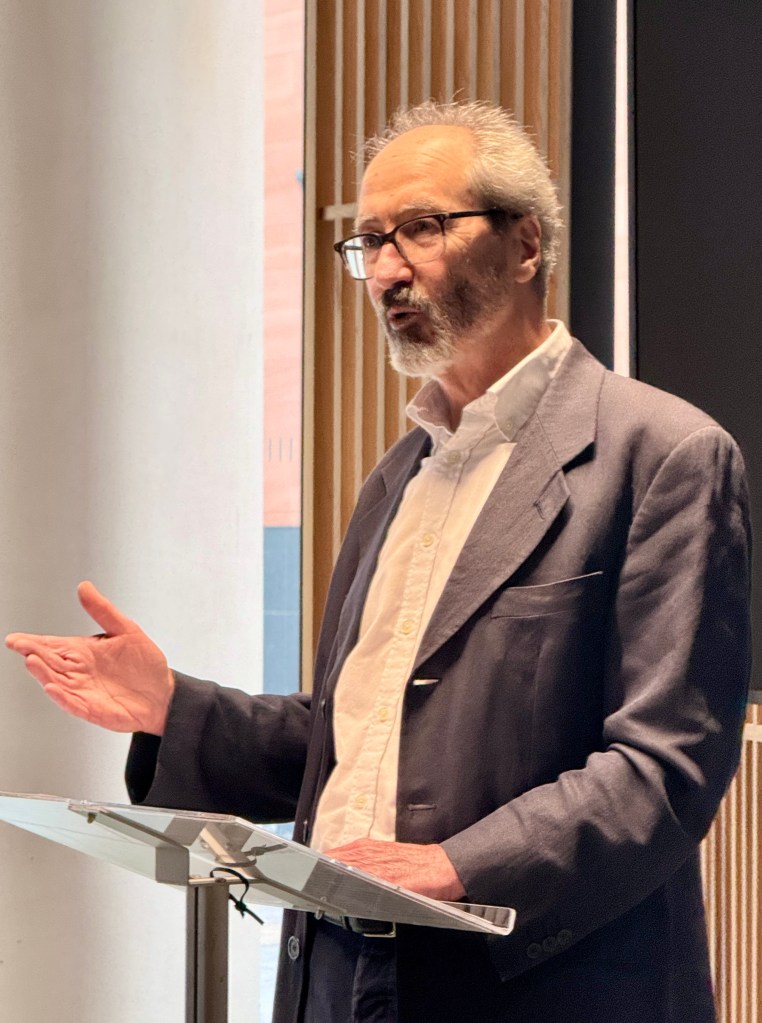

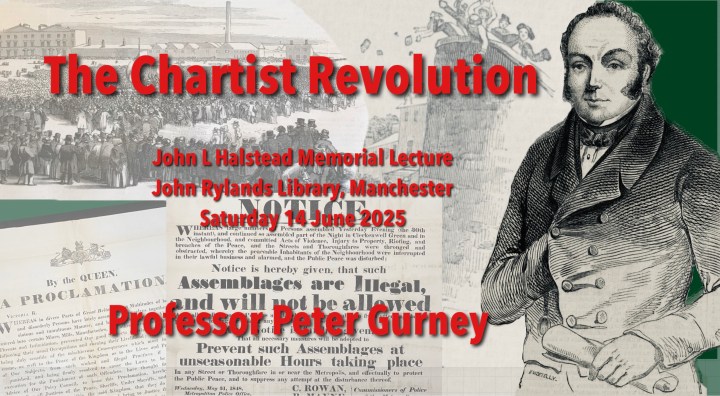

Liberal interpretations of the Chartist movement continue to dominate the views of historians and of general society, Professor Peter Gurney argued in delivering the Society’s fourth annual John Halstead Memorial Lecture at the John Rylands Library in Manchester in June.

Setting out to challenge the dominance of liberal readings which commonly argued that those Chartist demands which had proved feasible had eventually found their way onto the statute book while the movement’s more ‘unrealistic’ ambitions had been abandoned, Professor Gurney took as his lecture title ‘The Chartist Revolution’.

This ‘revolution’ however, needed to be understood in a broad sense. Chartist revolutionary ambitions were ‘more complex than a simple vanguardist revolution from above’, and whilst the movement had its ‘insurrectionary moments’, these were poorly organized, short-lived and not a feature of mainstream Chartism.

‘Between the late 1830s and early 1850s, Chartists were attempting to check and regulate one increasingly hegemonic way of life based on principles of individualism and competition, namely market capitalism and substitute for it a different way of life which as yet was only vaguely imagined but which was nevertheless prefigured by the social solidarity and co-operation that characterized the culture of the movement,’ said Professor Gurney.

‘To put this another way, and despite the emphasis on continuities between Chartism and liberalism made by “currents of radicalism” historians and post-modernists, Chartism was diametrically opposed to liberalism and the future it envisaged in relation to politics, economics and social life. The transformation Chartists envisaged cannot simply be grasped as an abrupt break with the past, a leap into a different world. This was a long revolution which like all revolutions involved a good deal of restoration and atavistic longing for an imagined past. Chartist ambition also needs to be grasped in its totality.’

Professor Gurney said that it seemed inconceivable to him that millions of men, women and children who had read and discussed the radical press, signed petitions, attended lectures, participated in demonstrations and much more, ‘that is, made the culture of the movement’, had been inspired simply by the demand for the vote and the right to elect MPs. Rather, the ‘suitably vague but ominous term’ the Charter and something more adopted by the Chartists themselves set out a greater ambition which ‘implied rejection of competition and market capitalism’.

He argued: ‘People were drawn to Chartism because it promised to change for the better the lives of their families and communities by radically transforming social and economic relationships. The dominant classes correctly perceived this as a revolutionary threat. After the defeat of Chartism the system of representative democracy that gradually evolved between the late 1860s and late 1920s bore little resemblance to the pure democracy advocated by Chartists. ‘

Liberalism, said Professor Gurney, meant the separation of the political from the economic ‘in practical reality as well as in theory.’ This was the antithesis of the Chartist approach. He quoted Feargus O’Connor, who made the point after 1842 that ‘political power is but a means and social happiness the end’.

And he continued: ‘A few years later, the young Frederick Engels made the same point in The Condition of the Working Class in England, also distinguishing between what he termed bourgeois democracy and Chartist democracy, the former limiting itself to constitutional reforms narrowly conceived, the latter demanding the franchise in order to transform social and economic circumstances. In this respect, as well as in others, Engels was learning from the Chartists, not the other way round.’

The changed realities of the 1850s and after had forced a rethink.

‘That certain working-class radicals made their peace with the new order after Chartism’s defeat is hardly surprising. Some managed to find common cause with middle-class radicals on a range of single issues including the tax on knowledge, temperance, women’s rights and legal reform to protect working-class associations. Some came to accept free trade and the separation of the political and economic domains that entailed as a kind of bargain.

‘Free trade finance simultaneously restrained working-class ambition and helped facilitate expansion of voluntary organizations that improved the lives of many working people in the second half of the nineteenth century by guaranteeing that the state left workers’ associations alone.’

But he added: ‘It is important nevertheless to recognize what was lost, namely the ambition to replace market capitalism with a humane and democratic alternative.’

Professor Gurney concluded: ‘Chartism continues to generate passion both within and outside academia because like the debate on the standard of living during the industrial revolution, the subject raises profound questions about the nature of capitalist society, questions that can’t be properly resolved this side of the cultural revolution that the Chartists practiced and hoped to generalize.’

But not everyone came to terms with these new circumstances. Like other great anti-capitalist movements that suffered defeat over the past two centuries, Chartism’s collapse had generated a good deal of introspection and melancholy and left some individuals with a deep aversion to popular liberalism.

‘One wonders how many ex Chartists lived in quiet hate after its defeat.’

The John Halstead Memorial Lecture is given annually in memory of the late John Halstead, one of the earliest members of the Society for the Study of Labour History and an active participant in numerous roles for six decades. John Halstead, 1936-2021.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.