My PhD investigates the lives and labours of social care workers in England and Wales between 1979 and 2010. Between 1979 and 1999, care assistants were the fastest growing sector of employment, increasing by 419%, while industrial jobs saw the greatest decline. Care work was, in many ways, the model of post-industrial working-class employment, characterised by low-paid, feminised, precarious, and emotionally demanding labour. My PhD considers how the political economy of social care shaped working conditions, and their implications for the lives of social care workers.

Thanks to the Society for the Study of Labour History, I was able to undertake numerous archives trips across the UK, which included visits to the Black Cultural Archives, Bolton Black History Group, British Library, Library of Birmingham, London Metropolitan Archives, Oxfordshire History Centre and West Glamorgan Archives.

The breadth of this research enabled me to compare and contrast the perspectives of governments and workers on social care and care labour. Building on previous trips to Tower Hamlets and Bolton, my work in the West Glamorgan/Neath Port Talbot and Oxfordshire archives focused on council records, particularly Social Services Committee records, as the bodies responsible for the administration of social care. In the political histories of the Thatcher, Major and Blair governments, the politics of, and changes in, local government have traditionally been somewhat neglected. The records of Social Services Committees, however, told a story of significant transformation in the period between 1979 and 2010. The Thatcher government came to power in 1979 and immediately set about reining in what it deemed wasteful and inefficient local government expenditure, taking various measure to restrict the funds available to councils. Local authority records provide stark and concrete examples of the effect of these policies on local communities and services. To take just a few examples, when the Thatcher Government introduced a system of spending targets and penalties for all authorities in 1982, Oxfordshire County Council responded by reducing staffing levels in its home help and residential care facilities by 5 percent and closing a residential care home. In April 1993, West Glamorgan County Council noted its serious concerns about the level of unmet care needs among its population; it underlined that the contraction of Government funding at a time of increasing demand on services due to an aging population and new community care initiatives had placed ‘extreme pressure on resources’.

These difficulties only became more pronounced after 1993, with the introduction of the purchaser-provider model, which reconfigured local authorities’ role from one of direct providers of care to an enabler of care. These reforms, in essence, privatised and marketized social care, with the state subsidising consumers to purchase care from a mixed economy of public and private providers. Local authorities everywhere, including in Oxfordshire and West Glamorgan/Neath Port Talbot, complained that the reforms were underfunded. The result of marketisation was intense downward pressure on the price of care services; different providers competed for council contracts by offering the lowest price possible, and the limitations of local authority funding meant that the contract price did not always cover the actual costs of caring. In both counties, from the late 1990s and early 2000s, confederations of independent sector social care providers regularly wrote to the council complaining that the low rate of reimbursement for services was threatening their financial viability. At the same time, the lower price for care services offered by private providers rendered council-run services uncompetitive. Both Oxfordshire and Neath Port Talbot externalised all their care homes to independent sector providers in 2000 and 2010 respectively, citing similar reasons—namely, that they did not have the funds to maintain the homes and independent providers could run the services more cheaply.

While council records clearly illustrated the strains upon the social care system, the voices of care workers themselves were largely absent. When staffing issues were raised, it was usually in the context of budgets and pay bills, staffing levels, and recruitment and retention initiatives, which while relevant, were impersonal. It was invaluable, then, to bolster my research in government archives with materials gathered from the Black Cultural Archives, Bolton Black History Group, British Library, Library of Birmingham, and London Metropolitan Archives, which focused much more squarely on workers’ experiences. These materials spanned the entire time period of my study and included surveys of the workforce, pamphlets and other print materials produced by workers, oral history interviews, and training and professional development resources. Most of the accounts emphasised the tensions between the interpersonal rewards of care work and the stresses created by poor working conditions. Among the most commonly cited grievances were concerns about low pay; unpredictable work schedules; high rates of staff turnover; and a desire to see more recognition and professionalisation of care work.

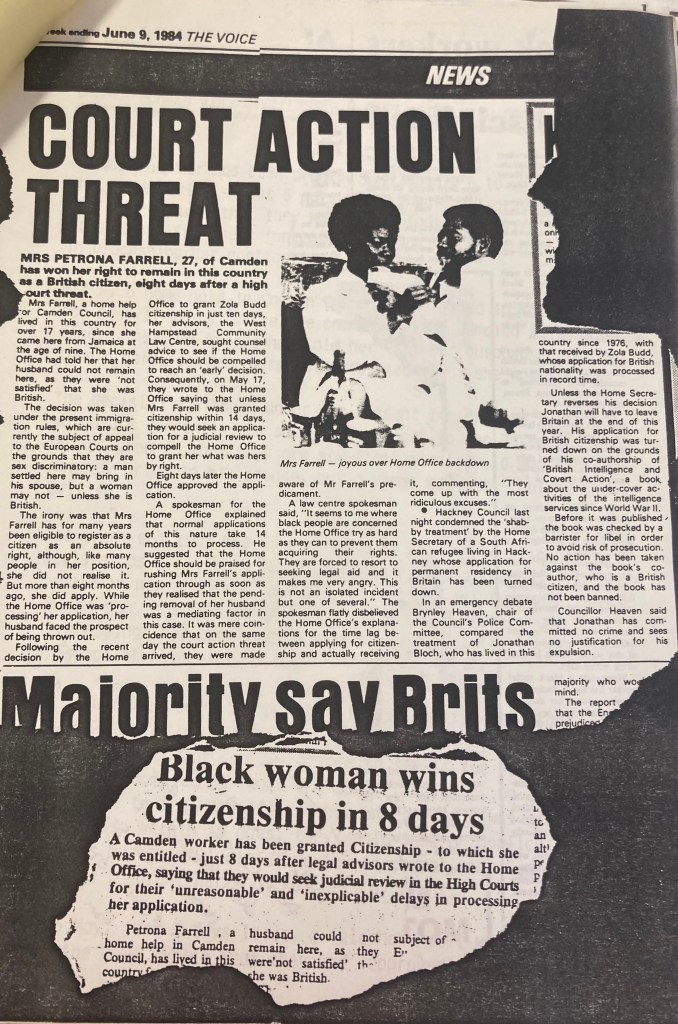

As part of this work, I made a concerted effort to track down materials that showcased the perspectives of Black and Minority Ethnic care workers, who although making up a sizeable proportion of the workforce have often been overlooked in the scholarship. The records at the Black Cultural Archives and London Metropolitan Archives suggested that race was an important basis of political and labour organising for workers in local government and other sectors of social care, especially during the 1980s. The Camden Black Workers’ Group and Black Workers and Patients Group both produced publications denouncing the concentration of Black workers in lower grade and lower paid jobs, the lack of equal opportunities in training and promotion, and institutional racism in the workplace. They ran anti-deportation campaigns, supported workers in disputes with their employers, and tried to work within trade union structures to demand greater action against racism. For example, when Petrona Farrel, a home help employed by Camden Council was wrongfully threatened with deportation despite being eligible for citizenship, the Camden Black Workers Group publicised her case and supported her to get legal representation, which ultimately led to her securing citizenship. Interestingly, the experiences of these radical London-based groups stood in contrast to the testimonies of South Asian care workers held at the Library of Birmingham, and those I collected from Black care workers at a community reminiscence session held in collaboration with the Bolton Black History Group. While there was agreement that care work was low paid (and indeed, this was widely observed by all care workers regardless of race), most of these workers recounted positive experiences of their work and emphasised that they felt supported by their white colleagues and managers.

Thank you to the Society for the Study of Labour History for enabling me to undertake this research which will form an integral part of my thesis and provoked a number of questions and ideas for my research.

Freya Willis is studying for a DPhil titled ‘Who Cares? Social Care Workers’ Experiences of Work, Gender, and Class in England and Wales 1979-2010’ at Magdalen College, Oxford.

Find out more about bursaries on offer from the Society for the Study of Labour History.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.