The National Association of Colliery Overmen, Deputies and Shotfirers (NACODS) was never a large trade union, but it was of major significance and importance in the coal industry because of the safety functions of its members.

When the union ceased to exist in 2015, with the closure of Kellingley Colliery, the last deep coal mine in Britain, its central records were thought to have been destroyed. But when its Barnsley head office, which had lain empty for nearly a decade, was transferred to the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) in September 2024, its new owners quickly identified archival material and called in professional help from the Modern Records Centre (MRC) at the University of Warwick.

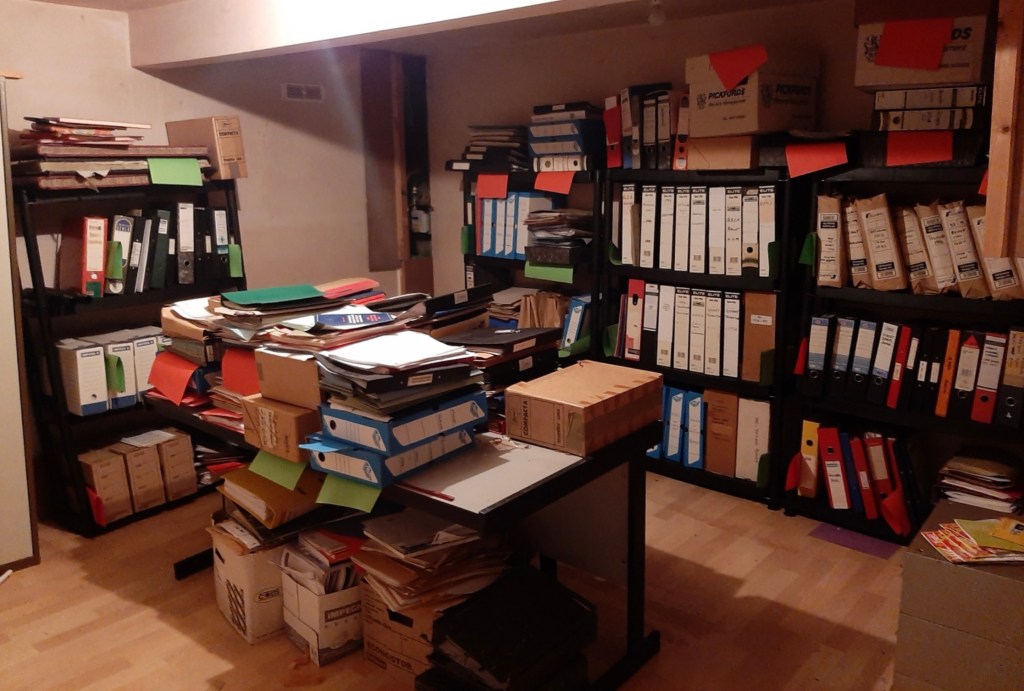

The building had been abandoned for nine years, and was found to have high levels of humidity, particularly in the basement where most of the records were stored. There were also insect pests including silverfish and evidence of rodent activity in the building. Some of the files were damp to the touch and mildew was developing on the paper. There was a high risk of a larger outbreak of mould if the records remained in that high state of humidity.

As project archivist at MRC, Liz Wood has over the past two years managed the transfer of the NUM’s archive from its head office, and is currently cataloguing the collection. She was the obvious person to assess the newly discovered NACODS collection, and with colleagues, drew up a plan to save some 80 records management boxes of material for long term archival preservation.

The material will first, however, need to go to specialist conservation firm Harwell, which also worked on the NUM archive, to be dried and deinfested, without which there would be a high risk of cross contamination of existing collections by insect pests and mould. This specialist process is expensive, and Liz Wood needed to find funding for the project.

The Society for the Study of Labour History agreed to make a grant of £1,000 towards the essential conservation work, and supported an MRC application to the National Archives for further funding. TNA agreed to provide the £5,000 balance from its ‘Records at Risk’ fund, meaning that conservation work could begin.

MRC staff then boxed up the records that are to be saved for the permanent archive, and earlier this week a van drew up outside the old NACODS office to take them to safety. After specialist conservation, the collection will later be taken to Warwick, where the records will be added to the important collection of coal mining trade union archives held there, ready for cataloguing and in due course made available to researchers.

Dr Quentin Outram, Secretary to the Society for the Study of Labour History and a specialist in the coal mining industry, dates the importance of NACODS and its predecessor union to the Coal Mines Act of 1887, which specified that a fireman, examiner or deputy (an ‘official’) must inspect every part of the colliery in which miners were to work for the presence of gas and its general safety before each shift.

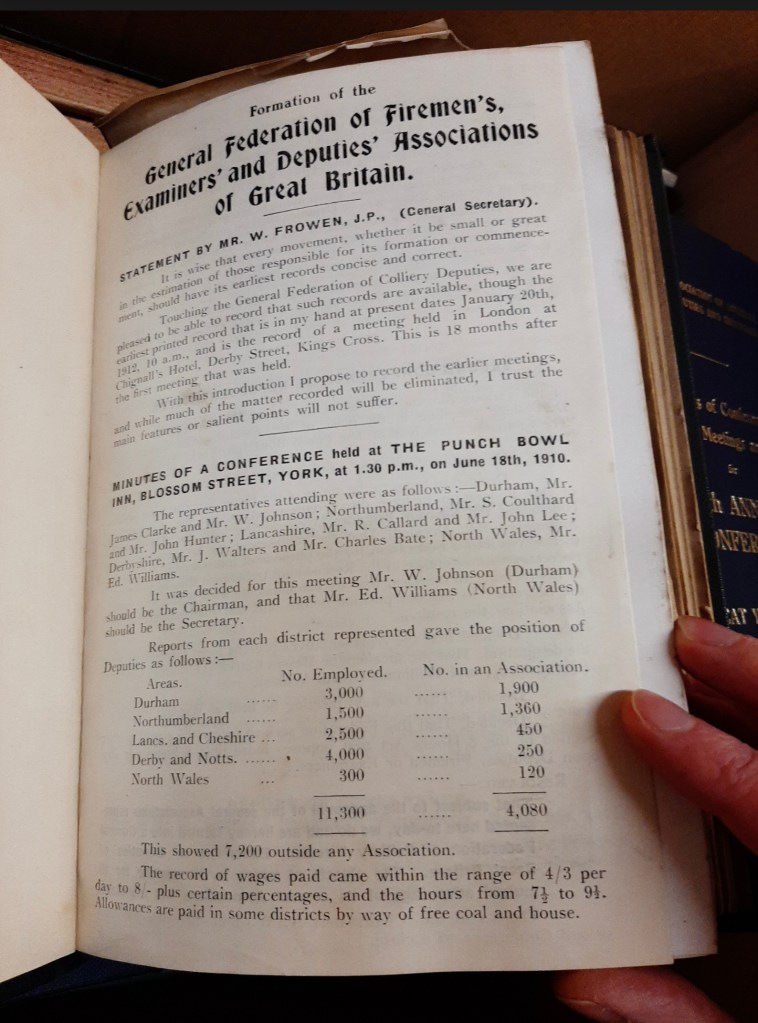

‘Should the mine be found to be in a dangerous condition the workmen had to be withdrawn. Effectively, no colliery could work if it had not been inspected by an official. This gave NACODS and its predecessor, the General Federation of Colliery Firemen’s, Examiners’ and Deputies’ Associations of Great Britain, which organized these officials a peculiar importance.

‘Before the 1980s this importance was primarily to do with its influence over the direction of safety policy and legislation. Its General Secretary from 1914 to 1939, William Frowen, was one of the main witnesses before the 1936-38 Royal Commission on Safety in Coal Mines and it was this that paved the way to the major post-nationalization revision of mine safety law, the 1954 Mines and Quarries Act.

‘In the 1980s its importance in coal mining industrial relations became crucial. NACODS retained its independence from the National Union of Mineworkers and at first stood apart from the 1984-85 coal strike after its members had failed to provide the two-thirds majority for strike action required by the union’s rules. It then, in September 1984, took another vote which gave an 81 per cent majority.

‘Had NACODS taken this step it is likely that the 1984-85 strike would have ended in compromise rather than in an abject defeat for the NUM. As it was, NACODS officials were bought off in negotiations with the National Coal Board and refused to call a strike in solidarity with the NUM. The role of NACODS was thus pivotal and its records from this time will generate intense interest.’

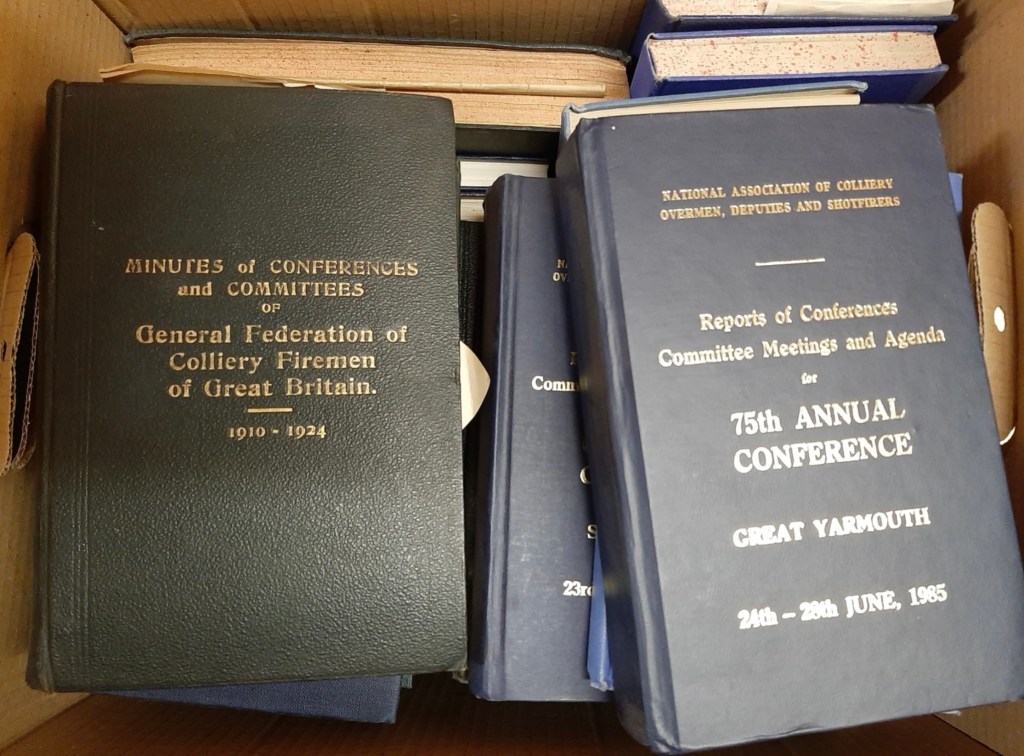

Liz Wood says that the archives found in the otherwise empty headquarters include a run of published minutes and conference reports dating back to the formation of the union in 1910 – no equivalent records have been found in other holdings listed on the National Register of Archives.

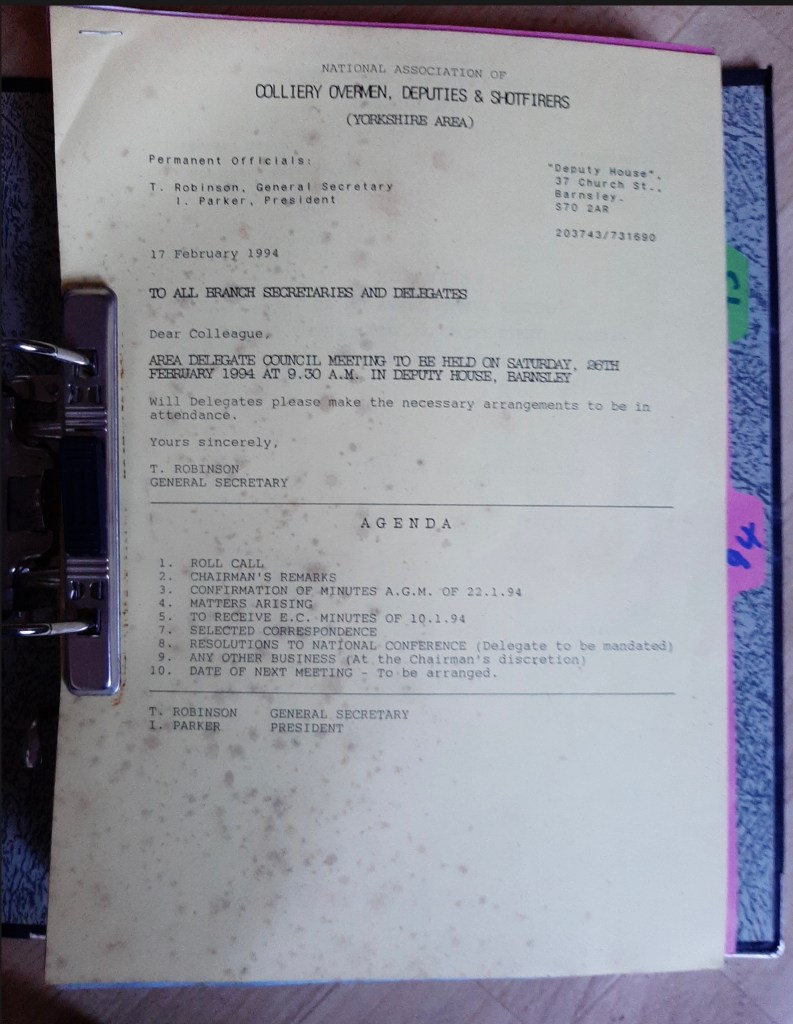

Manuscript minutes from the 1950s onwards have also survived. Most of the other surviving archives date from the 1980s-2000s and record the role of the union during a crucial period of change in the industry (files relate to the union at both national level and in the Yorkshire and Midland areas).

So far, says Quentin Outram, despite its significance, NACODS has received little attention from labour historians. The foundational histories of trade unionism in the coal industry by Robin Page Arnot (The Miners: A History of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain, 1889-1910 (London, 1949) and subsequent volumes) deal only with the MFGB and its affiliates which did not include NACODS and its predecessor, the General Federation. There is currently no narrative history available and even basic details such as its membership and the names and biographical details of its officers are hard to discover. The hope is that this will now change.

See also

Inside the NUM archive: 150 years of coal mining history

First tranche of NUM archives now indexed online in huge Warwick MRC project

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.