Jim Phillips introduces his new oral history of the miners’ strike in Scotland, its aftermath – and the long, but eventually successful – campaign to right the wrongs of 1984-85.

‘Mick always told us, when you’re talking, you’re not learning anything. You only learn by listening.’ This is Pat Egan, talking in June 2021 about Michael McGahey, President of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) Scottish Area, from 1967 to 1988. Pat was a young miner and union activist, raised in Lanarkshire but living and working in Fife by the early eighties. Pat was sacked along with another 205 men during the strike in 1984-85. He is among the 37 coal industry veterans, family members and supporters who were interviewed for Coalfield Justice, my new oral history of the strike in Scotland.

What do we learn, from listening to their stories?

The strike was a movement from below, and a movement of youth

Standard accounts, sometimes anti-union in tone, emphasise the role of Arthur Scargill, NUM President, in imposing a strike on a cautious or even reluctant membership. Crucial contra-punctual perspective came from Bob Young, NUM branch chairman at Comrie Colliery in West Fife, interviewed in March 2023. He told me about Scargill’s visit to Comrie on 5 March 1984. Dave Seath, National Coal Board (NCB) pit manager at Comrie, confirmed the essence of Bob’s story when I spoke to him a few weeks later. Scargill’s visit was interrupted when he received news, via the telephone in Dave’s office, that the NCB was moving to immediate closure of five pits in England, Wales and Scotland, and that his members in these areas were mobilising to defend their jobs through strike action. The NUM President left hastily, to coordinate rather than initiate this action.

Bob was forty in 1984, above the average industry workforce age of 37. Most of my other interviewees were younger still, men and women in their early thirties or, like Pat, in their twenties. Watty Watson of Lochore in Fife was sacked two weeks after his nineteenth birthday in November 1984. Veterans of the strike kept taking me back to the vibrant and dynamic world which they tried to defend as activists, with the majority of their working lives still in front of them.

Carol and Rosco Ross of Cowdenbeath in Fife provided particularly vivid testimonies. They were a married couple with two young kids in March 1984, a third was born during the strike. Carol and Rosco didn’t idealise the pre-strike world with its lingering religious sectarianism, everyday sexism and the life-limiting condition of being working class, but these defects were easing as a result of union action, public policy and social and cultural changes.

The injustices of the strike in Scotland were highly distinct

Strikers in Scotland were twice as likely to be arrested and three times as likely to be sacked than strikers in England and Wales. Scottish strikers were also liable to be convicted for innocuous actions: 94 per cent of 898 convictions were for breach of the peace, police obstruction or breach of bail conditions. In England and Wales, by contrast, a third of convictions were for more serious offences: police assault, ‘occasioning actual bodily harm’, theft, intimidation or watching and besetting, and riot.

The arrests and sackings are explained in Coalfield Justice as strategic injustice. They were concentrated on union officials and activists, to intimidate strikers and deprive them of leadership, preparing the ground for closures and intensified managerial control at surviving collieries.

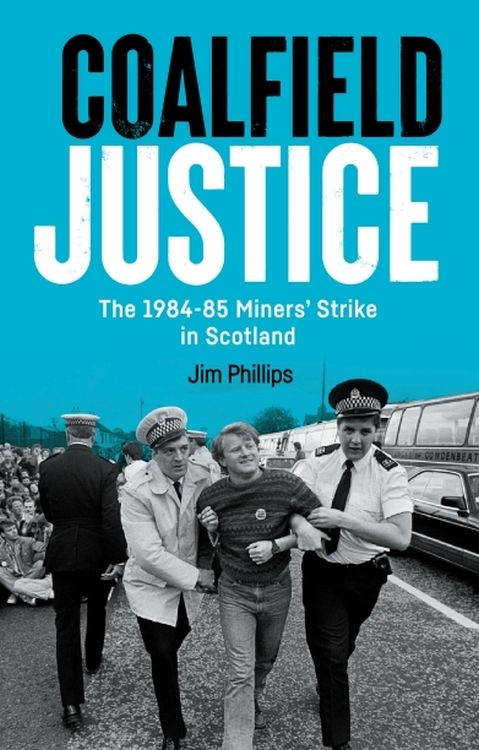

The book’s cover image, organised around a memorable photograph by John Sturrock, shows a key incident in this strategic campaign against the strikers: the arrest of Jim Tierney and around 300 others at Stepps in North Lanarkshire on 10 May 1984.

UK Cabinet office records show that the Stepps arrests in May were made by Strathclyde police officers operating under the instruction of Margaret Thatcher. The six coachloads of pickets were travelling to Ravenscraig, hoping to prevent strike-breaking coal imports from entering the giant steelworks. Norman Tebbit, Secretary of State for Trade and Industry in Thatcher’s Conservative government, viewed the potential suspension of production at Ravenscraig as the biggest single economic challenge arising from the strike.

Jim’s experiences exemplified the strategic exercise of justice. He was picketing coordinator for Clackmannanshire, Stirlingshire and West Fife, arrested in his community by a police sergeant who claimed in court that Jim had thrown stones at a vehicle carrying strike-breakers towards Castlehill Colliery in West Fife. Evidence to the contrary was ignored by the Sheriff, who found him guilty of breach of the peace. Jim was sacked from employment at Castlehill.

The government pursued wars of position and manoeuvre against the strikers

Thatcher’s government secured victory through what Antonio Gramsci would have termed a war of position as well as a war of manoeuvre. The government articulated a positional story about miners as inefficient workers and bullying thugs. This was used to justify practical manoeuvres taken by the police, the courts and the NCB: criminalising the strikers, controlling their movements and sacking them. These manoeuvres then reinforced the government’s positional story.

Hence the government’s presentation of major instances of disorder on picket lines, above all at Orgreave, the BSC coke works by Rotherham in South Yorkshire. Bob, Rosco, Pat, Jim and his Clackmannanshire neighbour Billy Fraser were all there on 18 June 1984. Before these interviews I assumed that this horrible event was over and done with in a brutal hour or two. Listening to the stories set me straight: violence against the strikers unfolded over an entire terrifying day.

The veterans also spoke about having to convince disbelieving friends and family members that the disorder was instigated by the police. This was a theme in other interviews. Jim Lennie of Bonnyrigg in Midlothian was sacked for alleged trespass at Bilston Glen Colliery. ‘They cannae jist dae that’, neighbours told him. ‘Ye musta done somethin’. This illustrates the power of the government’s positional claims: even folk in mining communities could not resist them entirely.

After the strike was harder than during the strike

‘Being a sacked miner was harder than being a miner on strike’, Watty told me. Pat felt unworthy of a pint in the pub or miners’ welfare club, because it was bought with solidarity contributions from other miners rather than wages that he was barred from earning. Jim Lennie related his sacking to the five stages of loss, or bereavement. ‘My identity was stolen’, he said.

Interviewees also spoke about the injustices imposed on communities with the rundown of mining employment after the strike: wider economic losses, problem drinking and drug-taking, physical and mental illnesses and early deaths.

But they talked positively of post-coal lives and careers, in various public services: transport (Watty is a train driver), education (Jim a retired principal maths teacher), health and social care, as health and safety officers, trade union officials (like Pat) or in benefits and pensions advice. They put their skills and experiences as trade unionists and activists to new use. In various ways they helped mining communities to remain cohesive and resilient

It is important to remember the strike in affirmative terms

The Scottish Parliament’s Miners’ Strike (Scotland) (Pardons) Act of 2022 is examined in the final chapter of Coalfield Justice. Strike veterans refused to accept the finality of the wrongs experienced in 1984-85. Their campaign was headed by the NUM in Scotland, led by Nicky Wilson, and its lawyers, Thompsons Scotland, guided by Bruce Shields, and in Parliament by the MSPs Neil Findlay and then Richard Leonard.

Neil brought me into the campaign in 2013. We persuaded the Scottish government to establish the Independent Review of Policing in 2018, chaired by John Scott, QC, with Dennis Canavan, veteran coalfield MP and MSP, among its members. Public consultation in coalfield communities contributed to its single recommendation of collective pardon for those with public order convictions that had not resulted in jail sentence.

Implementation was delayed by Covid-19 and the Scottish Parliament election of 2021. A Bill was published in October 2021 which enabled pardon for convictions arising from arrests on picket lines but not in communities. In the winter that followed campaigners pushed to expand the pardon’s remit. I gave evidence in January 2022 to the Parliament’s Equalities Committee, online, with Nicky Wilson, Bob Young and another of my interviewees, Alex Bennett, of Midlothian. I spoke about a dangerous hierarchy of justice, if strikers arrested on picket lines were pardoned while those arrested in communities, including Jim Tierney and Watty, were not.

The Scottish government moved. The remit was broadened: all strikers with convictions for breach of the peace, breach of bail and police obstruction were pardoned. This achievement was celebrated by 50-plus veterans, family members and supporters at the Parliament when the Bill passed its final stage in June 2022. McGahey’s aphorism, remembered by Pat in 2021, held true: the government and Parliament in Scotland had learned about injustice from listening to the veteran miners, and they had taken remedial action. Oral history was hugely validated. I hope readers will see this too in the pages of Coalfield Justice.

Jim Phillips is Professor in Economic & Social History at the University of Glasgow, and author of Scottish Coal Miners in the Twentieth Century (Edinburgh University Press, 2019) and with Valerie Wright and Jim Tomlinson Deindustrialisation and the Moral Economy since 1955 (Edinburgh University Press, 2021).

Coalfield Justice: The 1984-85 Miners’ Strike in Scotland, by Jim Phillips, is published by Edinburgh University Press.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.