What lessons should a Labour Cabinet which numbers five history graduates in its ranks* take from the experience of previous Labour governments? And how might the party’s past be used to help shape its future?

In the fortnight leading up to the general election on 4 July, the Labour History Research Unit (LHRU) at Anglia Ruskin University surveyed historians of the Labour Party and modern Britain to find out which previous administration they thought Keir Starmer’s government would most resemble. The survey also asked historians to comment on ‘the myths Labour lives by’, and its past commitments to socialism and social equality.

Of the 34 working historians who took part, the largest number (16) thought the new government most resembled that of Harold Wilson in the 1964-70 period. Wilson’s team had to deal with serious economic shocks (devaluation of the pound) while also producing social legislation that has stood the test of time, on abortion, equal pay, and the abolition of capital punishment.

A significant number (9) felt the 2024 government would be closer in spirit to the Blair-Brown governments with their centrist focus on modernisation. There did, however, seem to be a consensus that the Attlee government is not a useful guide, even though it is often viewed as Labour’s greatest administration. There was only a single vote each for 1929, 1945 and 1974, with four opting for 1924.

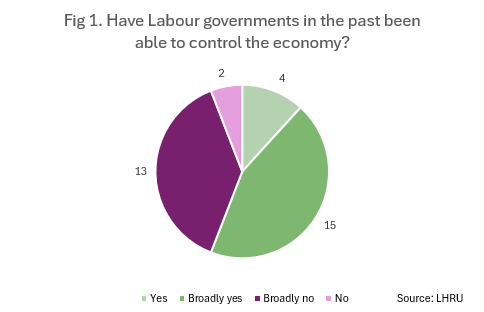

Asked ‘Have Labour governments in the past been able to control the economy?’, a slim majority said definitely or broadly yes (see fig 1). There was a similarly close split on the question of whether Labour governments generally leave the constitution unchanged: 18 said yes, and 16 said no.

Those who felt Labour has changed the constitution point to its policy of devolving power to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (while resisting independence and insisting it is a four nations party). Harold Wilson introduced votes at 18. New Labour introduced the Human Rights Act, the Freedom of Information Act, the Supreme Court. This, however, made the Blair governments unusual.

Most respondents, however, considered the 2024 manifesto too timid as a programme for government: 17 thought it ‘too timid’, 13 ‘about right’, and none thought it ‘too bold’.

Many of those taking part in the survey had thoughts to share about ‘the myths that Labour lives by’. Professor Jon Lawrence (Exeter) noted that the Prime Minister’s first name is Keir – evidence of the way supporters feel the weight of the party’s history.

Several historians noted that Labour regards itself as the party of the working class, and that though this link remains, the party since Tony Blair has been more meritocratic and aspirational. Dr Christopher Massey (Teesside) noted that the party had abandoned Clause 4 (which committed Labour to nationalisation) under Blair, and that the clause that replaced it focused more on equality of opportunity than outcome.

A number pointed to the record of the Attlee government and the ‘Spirit of 1945’ which continues to animate the party. In particular, the identity of Labour as the party that created the NHS is central to its ethos. Dr Malcolm Petrie (St Andrew’s) observed that the 1945 government is the only one that really appeals to both left and right of the party. But this focus on the 1945 government is also a problem according to Professor Tony Taylor (Sheffield Hallam) as it sets an ‘impossibly high benchmark’ leading to all subsequent governments being viewed as failures.

A number of historians argued that Labour is often selective in its use of its history, which is frequently deployed for political purposes. And there was a divide between those who saw continuity between the Labour governments of the pre-Blair era and the Starmer government today, and those who argued that the older Labour Party ended in the early 1990s, and has been replaced by ‘a rather different party. As the report notes: ‘This division is likely to be a continuing faultline both in histories of Labour but also in wider political discussion.’

In its conclusion, the report notes that Keir Starmer’s leadership has ‘shown relatively little interest in Labour’s past’. This is, it says, entirely understandable. ‘Nostalgia can be a dangerous thing and successful parties need to grapple with the problems of the present moment.’ It also remarks that, ‘The Labour leaders who have been most aware of the party’s history (Foot, Kinnock) have been the least successful.’

However, it adds: ‘The party of 2024 has learned from Labour history that it is better to under promise and over deliver. In contrast to previous Labour plans to transform society (the 2019 manifesto), the party now prefers to settle for small victories. Some of the soaring Labour rhetoric of the past is absent in the party’s presentation: it now seems more comfortable with the Union Jack than the red flag. Starmer talks both about “change” and a “changed Labour party”. He may find he has more in common with the six men who have been Labour Prime Ministers in the past.’

Commenting on the findings, Professor Rohan McWilliam at the LHRU said: ‘We were really struck by the thoughtfulness of the responses. We generated some data from the replies but also wanted to share the insights that colleagues provided. They confirm our view that historians have a lot to contribute to contemporary politics. Amongst other things, they strip away many of the myths about Labour and view its successes and failures in a deeper perspective. There was little nostalgia and no recourse to easy answers. Historians of both the Labour Party and the labour movement have always understood that they are both retrieving a past but also making a contribution to the debates of their times.’

The survey findings sit alongside an LHRU report titled How Labour Governs that focuses on domestic policy, foreign policy and the special case of Labour’s relationship with Ireland.

The report argues: ‘We do not believe that history offers simple lessons. This would reduce Labour to the level of the generals always fighting the last war. Nor do we believe that history helps predict the future. Nevertheless, we can think with history to understand the challenges of today.’ And it concludes: ‘The records of the Attlee, Wilson/Callaghan and Blair/Brown governments are instructive. Historians can offer some direction. Labour is cautious because of the precarious state of the public finances, but, in the words of Rahm Emmanuel (at the time chief of staff to Barack Obama), ‘Never let a serious crisis go to waste’.

How Should Labour Govern? Historians Respond. A survey by the Labour History Research Unit, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge.

How Labour Governs, A report by the Labour History Research Unit, Anglia Ruskin University, July 2024.

Historians in government

The new Cabinet includes five history graduates. They are: Wes Streeting, Health Secretary; Jonathan Reynolds, Business Secretary; Liz Kendall, Work and Pensions Secretary; and Bridget Phillipson (history and French), Education Secretary. Alan Campbell, Chief Whip, has an MA in history following a first degree in politics.

In addition, Professor Pam Cox, (University of Essex), a former chair of the Social History Society, has been elected Labour MP for Colchester.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.