With the National Union of Mineworkers’ archive now transferred to the Modern Records Centre, work is under way to catalogue this vast collection and decide how it can best be made available to researchers and mining communities. Mark Crail reports on the story so far.

On a chilly morning in January 2023, a lorry drew up outside the Modern Records Centre at the University of Warwick and unloaded several crates piled high with archive boxes and secured in pallet wrap. Over the following twelve months there would be three more such deliveries as the archives of the National Union of Mineworkers completed their journey from the NUM head office in Barnsley via specialist conservators to what will be their final home in humidity- and temperature-controlled secure storage on the university campus from where they will eventually be made accessible to researchers.

The collection is vast, running to 300 metres of shelf space. The largest collections relate to the NUM as a national body and especially to the Yorkshire miners. But it includes records dating back to the 1850s, and from many of the country’s former county and district miners’ associations, and from the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain. It includes registration books, accounts ledgers, minutes and other administrative records, and a huge collection of material relating to the medical needs of sick and injured miners.

Accumulated over more than a century and a half at the miners’ union headquarters, first in London, then Sheffield, and since the mid-1980s in Barnsley, and at the union’s once-numerous area offices, the archive came into being as a series of collections of working documents. It was never intended to be an historical research archive, and neither were the Barnsley office and its magnificent Edwardian Miners’ Hall designed to cope with the scale of paperwork they eventually came to house. That it survived and will eventually be thrown open to academic and non-academic historians, schools and others in the former mining communities is a testament to the importance with which the NUM’s officials and members view their history and heritage.

The National Union of Mineworkers came into existence on 1 January 1945, but its history stretches far back into the nineteenth century. Though many early attempts to form mining unions left no lasting organizational legacy, some, including the South and West Yorkshire miners’ associations (both dating to 1858), the Durham and Cumberland miners’ associations (founded in 1872), and the National Federation of Colliery Enginemen (1873), survived along with other later associations to provide the core of a new national organization. This Miners’ Federation of Great Britain was formed at a conference in Newport, South Wales in November 1889, and within a year, the MFGB could claim a membership of 250,000 rising to 600,000 by 1910 as the Northumberland and Durham miners’ associations joined up. Importantly, the federal structure meant that affiliates retained their independence and identity. Membership peaked in 1920 when the Federation had more than 945,000 members. But in the wake of the 1926 general strike, dropped to 756,000 and had fallen to about 530,000 in 1930. The organization was renamed the Mineworkers’ Federation of Great Britain in 1932, reflecting the creation of groups for enginemen, firemen, electricians and other workers in the industry.

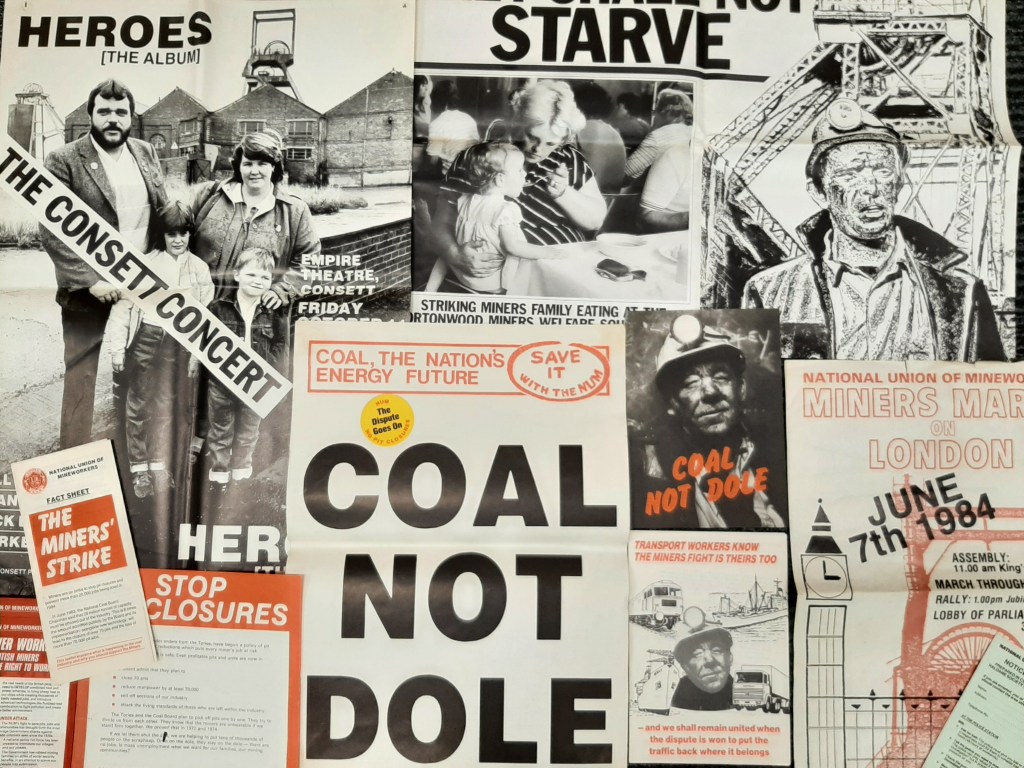

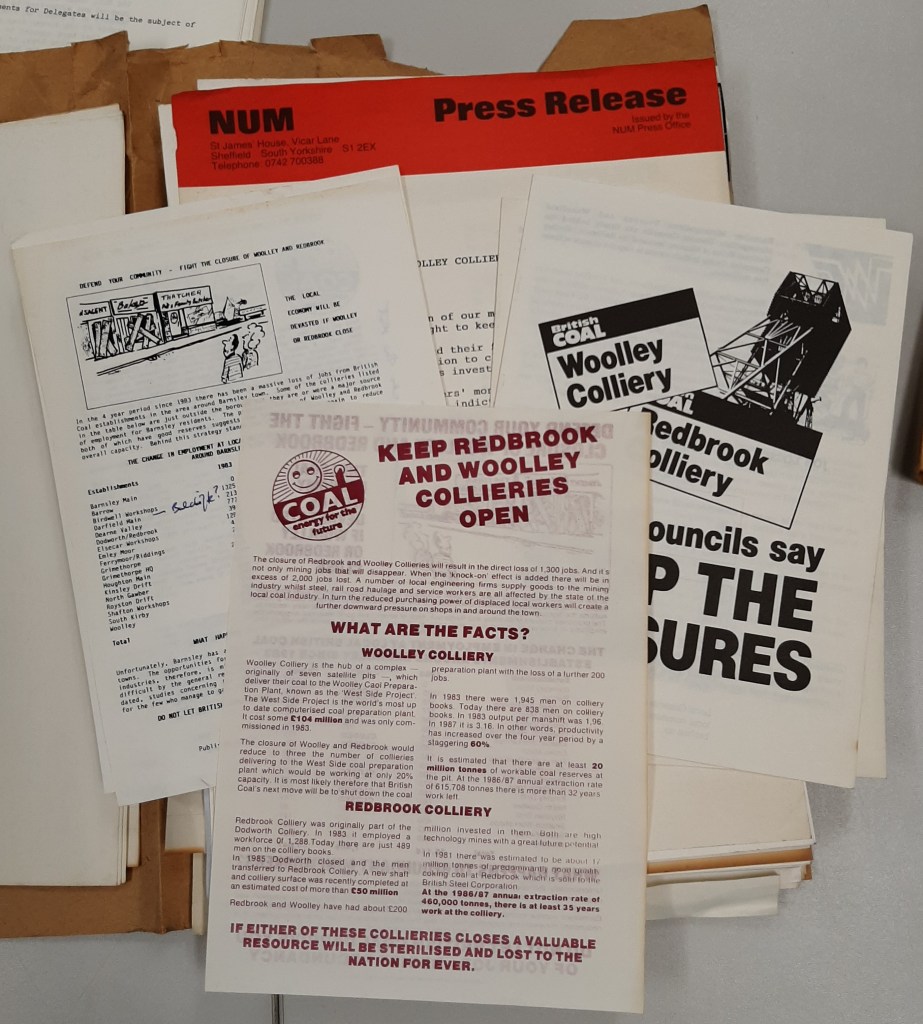

War-time centralization of the coal industry required an organizational response from the union, and with nationalization imminent the MFGB became the National Union of Mineworkers in 1945, its constituent associations retaining some degree of autonomy and with their own officials, but becoming district associations of the new more centralized union. In the post-war years, employment in the mines continued to decline, partly through pit closures and partly due to mechanization and increased productivity. By the early 1980s, there were 231,000 miners working in 173 pits. Then in March 1984, the National Coal Board announced plans to close 20 more collieries with the loss of 20,000 jobs. The NUM claimed that there were secret plans to shut at least 70 pits – though it was not to be until the release of Cabinet papers in 2014 that these claims were to be proved true – and the last great strike in the industry began that same month. This is not the place to tell the story of the strike; however, in the years that followed, the industry was to be privatized and further run down. By 2009, there were just six working collieries, and in December 2015 the last deep mine in the UK, Kellingley Colliery, closed for the last time, bringing an end to centuries of deep coal mining.

As coalfields disappeared, employment in the industry vanished, and the NUM was forced to close down its area structure, the surviving records of these ghost organizations, those that were not lost or destroyed, made their way to Barnsley, where they joined a century and a half of Yorkshire and national union paperwork accumulating in what was once the office of the South Yorkshire Miners’ Association. That a vast quantity of that material has survived and will continue to inform histories yet to be written is down in no small part to Paul Darlow, a former Barnsley miner turned NUM archivist.

Though Paul Darlow left the pits in 1990 to gain a history degree and start a new career in teaching, he never lost interest in the union’s heritage. In 2016, when he became involved in a National Lottery-funded education project on the 1866 Oaks Colliery disaster, in which 361 men and boys died, he seized the opportunity to look around the Barnsley building. ‘It’s part of mining history,’ he says. ‘It’s a place I always thought I would love to get inside – and it really does take your breath away.’ The office in Huddersfield Road dates to 1874, and the attached Miners’ Hall to 1912. ‘It’s a nonconformist chapel, basically,’ says Paul Darlow. ‘It’s got a pulpit at the front, stained glass in the windows… That’s the tradition they were coming from, so that’s the sort of building they wanted.’

What he found inside, however, set him on a new path. ‘To tell the truth, the archives were in a right state. They were in eight different places throughout the building and hall. It looks to me as though people just picked up piles of paperwork and shoved it anywhere they could. When they finished with it they just put it in a box and someone found some space for it in a room.’ Papers that found a home in offices or the Miners’ Hall were still in good condition, but that was not the whole story. ‘The material in the basement was becoming seriously damaged because it was not in a conducive environment to archive it properly. There was stuff in the garage where there was a small store room that was covered in dust. It was basically rotting.’

Paul Darlow realised that something had to be done. ‘When I saw the state it were in I needed things to happen because it would have gone by now. Not all of it but a percentage. And it would have been lost. Being the historian that I am I just thought that I couldn’t let this happen.’ In consultation with NUM general secretary Chris Kitchen, he involved Dr Jörg Arnold, a historian at the University of Nottingham whose book The British Miner in the Age of De-Industrialization (OUP, 2023) drew on the archives in Barnsley. Together they were able to get funding for a scoping exercise.

Ideally, there would have been a way to secure the archive’s future at the Barnsley building. But that looked to be unachievable. ‘I said to Chris Kitchen that it breaks my heart to say this, but it needs to move. Getting the building converted into an archive would have cost a million quid and taken years – and we didn’t have years. We knew it had to go to a professional archives. Part of me thought this is an important part of Barnsley and it should stop here, but you have to make the decision that either it stays here and rots or it goes to Warwick and people can access it.’ And that is the decision that was made.

With input from Professor Keith Gildart at the University of Wolverhampton, himself a former coal miner, and Dr Quentin Outram at the University of Leeds, both members of the Society for the Study of Labour History’s executive committee, and others, the team at the Modern Records Centre put together a funding bid that brought in a main grant from the Wellcome Foundation and additional money from the Pilgrim Trust and National Manuscripts Conservation Trust specifically for the conservation work that would be needed.

After a substantial delay caused by covid lockdowns and restrictions, a team from the Modern Records Centre was finally able to visit Barnsley to see the archive for themselves. Liz Wood, now the project archivist for the NUM archive, says: ‘The archive manager and three archivists went up for several days to get an idea of the scale of it and how much of it was material we would want to take. Because of the amount of stuff you couldn’t look at every box and every file. There were literally rooms and rooms of material. So we had an initial look, got an idea of what was there, and what sort of condition it was in. Later, in the summer, two of us went back for a more in-depth appraisal, and we marked up the stuff we wanted to take on the shelves with a traffic-light code with green sheets of paper for go, red sheets of paper for stay.’

She echoes Paul Darlow’s description: ‘There was the garage which had multiple rooms, there’s a cellar, there are at least three attics, some of which have multiple rooms, and there were a lot of spaces with records kept in different conditions. The Miners’ Hall is a fabulous space but the archive material, which obviously arrived there from different places, was basically in whatever space they had available. It is just one of those things that has accumulated over the years.’

The Warwick team were also concerned about the damp conditions in some areas, and on the advice of conservation and health and safety experts, wore hazmat suits when handling material. ‘This is the material that we took first. But we were lucky in a way because a lot of it was ledgers. If it had just been paper with no thick covers it would all just have rotted. But because these were quite chunky nineteenth and early twentieth century volumes with thick covers, the damp had got so far but not, for the most part, into the main pages.’

The first four lorry-loads of material left Barnsley in June 2022. Their destination was a specialist company called Harwell Restoration at Didcot. Here the papers were freeze and vacuum dried to remove damp, and irradiated to kill mould and any insect life that might have found its way into the documents. The company also used conservation vacuums, brushes and sponges to carry out some dust removal and cleaning before packing everything into archive boxes and sending it on to Warwick.

Rachel MacGregor, digital preservation officer and acting archives manager at the Modern Records Centre, says: ‘Usually when stuff comes in, it’s between one and five linear metres, a few boxes. Occasionally we have bigger collections, but with something of this size you have to do a lot of planning to accommodate it. Most places would not have that much spare space to put it in. Just from a practical perspective, it is a massive deal for us. Even leaving aside the cultural and historical significance of the collection, just the sheer scale of the collection was a challenge.’

Fortunately, the university had recently completed building new archive storage facilities. Some of the Modern Records Centre’s less-used collections were moved to this nearby but off-site building, and the NUM papers housed in temperature- and humidity-contolled secure storage on the campus site.

Seconded for three years to make sense of the vast archive, Liz Wood is now working her way through every box, examining every file, and creating a draft catalogue as she goes. She says: ‘Normally when we catalogue, we do it straight on to our cataloguing software. Because of the scale of this, because it is in all sorts of different places, I am doing it on Excel spreadsheet first so I don’t have to continuously rearrange stuff in the catalogue. We are hoping to have gone through the bulk of it by late summer this year.’

The archive promises to be of huge interest. ‘It’s not just labour historians, it’s local historians, family historians, medical historians because there is material about workplace injuries and illness,’ says Rachel MacGregor. ‘We are conscious that the stories that are told here are not ours. It all belongs to the NUM, but even more than that it belongs to those communities where mining is part and parcel of their heritage.’

Paul Darlow found many treasures while caring for the archive. ‘One of the most interesting things I found with Quentin [Outram] when we were looking through various books was that someone had stuck in leaflets and flyers, some dating back to the 1870s. And I lifted one of them up to have a look and it was a check weighman’s book. I don’t think I have ever seen a check weighman’s book before.’ He also discovered records of his own grandfather’s employment as a miner, beginning in 1912. But he adds: ‘This isn’t really about individuals, it’s about the collective. Some of the most important stuff is about seeing the big picture. In the 1950s, for example, they weren’t on strike every two minutes at national level and it is thought to be a fairly quiet time, but on a local level there were strikes all over the place.’

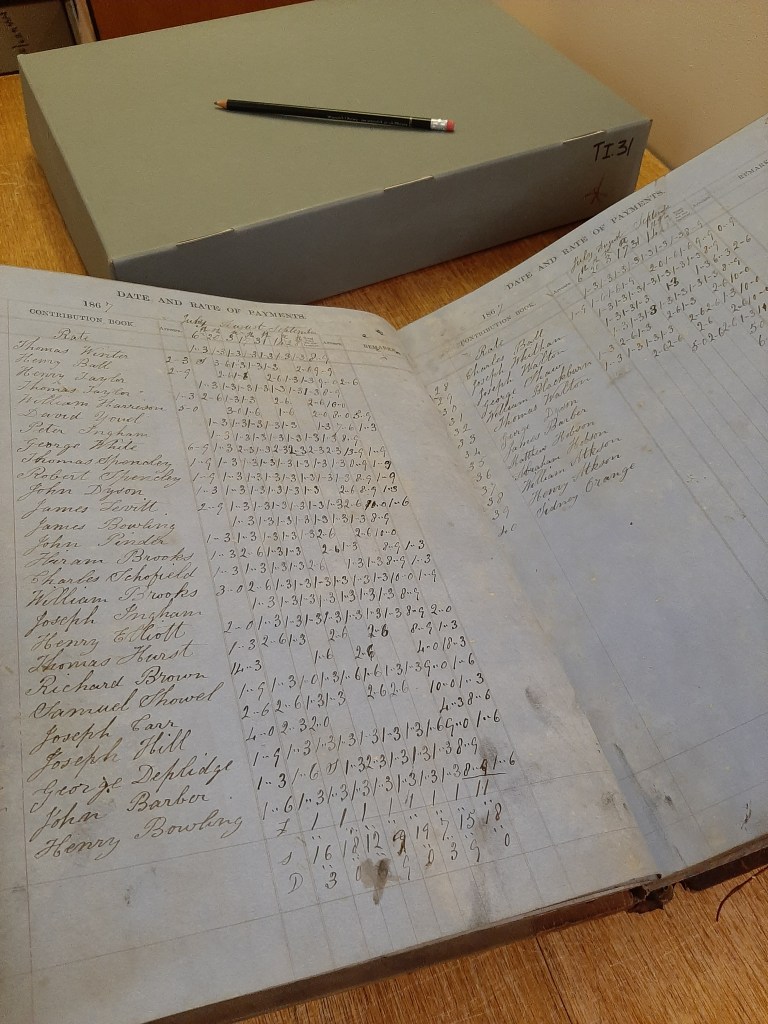

The earliest documents to come to light so far date from 1858. Liz Wood says: ‘I’ve got a branch registration book, so basically membership records. In that particular case that’s the South Yorkshire Miners’ Association Darley Main lodge, 1858-1876. A lot of the early records dating back to the 1850s, 1860s and 1870s are financial or membership records. They are not comprehensive, but there are surviving ledgers which list individual members and in some cases family members as well. Some of the financial records can include benefit claims, so if there was a fatality there might be a reference to a payment to somebody because of that.’

But one particular twentieth century record caught her eye. ‘I was going through a box from the 1940s, during the second world war, and there was a flash of colour, and it was a leaflet for the Lidice Lives campaign. Leamington, which is near here, is where the Czechoslovakian special forces trained. These were the special forces who killed Heydrich [the Nazi governor of Bohemia]. But I didn’t know about the connection with the mineworkers and Lidice, the village exterminated in revenge. Lidice Lives was started by the mineworkers in Staffordshire because it was a mining area. So that linked in with mining union activity locally but also the part they played in the international trade union movement, and more generally with broader solidarity.’

Cataloguing still has a long way to go, but thoughts are already turning to publicity and outreach work. ‘We want to tell people it is here, and we want to encourage people to get excited about it – but we don’t want them to get too excited because it is not available yet,’ says Rachel MacGregor. Some material will be digitized – though primarily as a publicity tool, she adds. ‘Selections are likely to be older and to be visual, perhaps with graphics, because with the best will in the world, pages and pages of text are useful and valuable if you are studying that particular thing, but usually it is less useful for promoting the archive.’

The archive also needs to cater to different audiences, she says. ‘We are conscious that the stories that are told here are not ours. It all belongs to the NUM, but even more than that it belongs to those communities where mining is part and parcel of their heritage. They are stakeholders within this, and many of those communities are quite a long way from Coventry. There are many, many barriers for people in some of those communities getting to us – not just financial, but physical and cultural reasons why they may not ever wish to or feel comfortable coming to a university that is a long way from where they are. So with that in mind we are thinking about ways we can try to make it accessible to people who really would want to access the collection.’

She adds: ‘An academic may be able to come and do a deep dive, and we don’t need to do anything other than tell them to look at the catalogue, whereas to enable the same level of access for another person, we will have to do more. We are going to have to learn how to do this, and ensure that we are taking people with us.’

As she works her way through the boxes, Liz Wood is keeping an eye out for material that will help engage different audiences. ‘When we get to the outreach side, a chunk of that will be looking at the health and welfare aspect. Obviously due to the dangers of the industry there is stuff to do with accidents, and with things like dust and respiratory illnesses. So there is material that covers both the union’s work to improve the conditions of its members and its work trying to support them when they were unable to work or if there was a fatality to support the family.’

Forty years on, she says there is material relating to the miners’ strike of 1984-85, though much of that is still in boxes that only arrived at the end of January 2024 and has not yet been catalogued. Looking at earlier national strikes she says: ‘There is not so much from the 1920s, but there is good stuff from the 1970s – both 1972 and 1973-74, the three-day week and so on. I was going through some of this last week and there is interesting material looking at the organization of the dispute, from the sending of flying pickets from Yorkshire to more general material on the control of the dispute.’

As time goes by, memories fade, and especially outside the former coalfield communities new generations are less aware of Britain’s coal mining history. ‘If I’m talking to a group of adults who are forty plus, I just say NUM and they know what I mean,’ says Rachel MacGregor. ‘But with younger people I have to spell out National Union of Mineworkers and explain that this was a really significant organization and a huge industry. It doesn’t have the same cultural resonance because they don’t remember it.’

Paul Darlow admits that he was unable to watch as the archive boxes were loaded up and driven away at Barnsley. ‘I was in the building, but I just couldn’t,’ he says. But despite the vast amount of material that has been removed, the building is far from empty or deserted. The NUM’s motto is ‘The Past We Inherit, the Future We build’, and the union’s staff continue to work on issues such as pensions, industrial diseases, concessionary fuel schemes and welfare. As the NUM website declares: ‘There are still wrongs to put right and agreements to protect.’ Around 10% of the original archive also remains on site – primarily printed reports or pension records relating to individuals – though with more space available it is no longer housed in the damp and dusty garage. And there is a steady stream of visitors, including school parties, eager to see the Miners’ Hall for themselves.

Paul Darlow says: ‘When we have school groups come in, I tell the kids that this is their history. I always say I have never met a king or a queen, but I have met a lot of miners. I want them to realise it is about them – and they do. We have a small museum in the hall which has a firework with a picture of Mrs Thatcher on it. One kid said to me, “my grandad hates that woman”. People here remember.’

He adds: ‘For me, this is the most important archive in the country. People say, well the National Archives has Magna Carta; but what we have here is the Magna Carta of working-class history.’

* Our thanks to Paul Darlow at the NUM, and to Rachel MacGregor and Liz Wood at the Modern Records Centre for their help with this article. We repeat their plea to be patient while work continues to make the archive accessible. Researchers cannot access the collections until this work is completed.

Mark Crail is web editor for the Society for the Study of Labour History.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.