My PhD researches the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) and its relationship with anti-militarist and pacifist ideas from the First World War. The thesis reassesses the political development of the CPGB by focusing on the conscientious objector cohort that joined the Party following its formation in 1920. I explore the impact of the 1917 Russian Revolutions on the largest anti-war group, the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF), and the role its former members played in the CPGB’s anti-militarist campaigns throughout the 1920s.

The 1927 Soviet War Scare, a belief that Britain would soon invade the Soviet Union, forced British communists to confront the issue of war resistance head on and in some respects marked the swansong of the conscientious objector group. Internal discussions on the CPGB’s response to potential war highlighted a continued belief in passive resistance as opposed to the more extreme, yet ideologically sound, methods of Revolutionary Defeatism. Further research at archives funded by this bursary has allowed me to develop this argument, and suggest that the replacement of the Party leadership in 1929, many of whom were former conscientious objectors, could have derived from an advocacy of such ‘backwards’ anti-militarist methods.

The Catherine Marshall collection in Carlisle was fruitful in helping me to explore the mind-sets of key anti-militarists during the First World War. As Marshall was a leading member of the NCF, her papers gave me a unique insight into the organisation, and helped to highlight how the radicalisation of local branches frustrated her attempts to project a more moderate image for the movement.

Strikes led by conscientious objectors in work camps and prisons were accompanied by support for Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils, direct emulations of Russian-style Soviets. These events not only emphasise the impact of the 1917 Russian Revolutions, but help to mark the inability of the leadership to control the NCF’s ever-growing divergences, hastening the Fellowship’s termination in 1919. An internal report produced at this time noted that the international pacifist movement had been split into ‘(1) Anti-Capitalist and Anti-Militarist, and (2) Absolute Pacifist’ blocs. It also lamented that ‘there is no distinctive work of a pacifist character to justify the formation of an entirely new body’ to supersede the NCF. Instead, activists ‘who desire to be associated with fellow pacifists in an organised capacity’ were advised to co-operate with pre-existing bodies, including Quaker bodies, socialist movements and ‘any Pacifist Communist Group that may be formed’.[1] This document is key not only in highlighting the divisions which had engulfed the NCF, but also confirms the extent to which communism had carved a space for itself within the British anti-war movement.

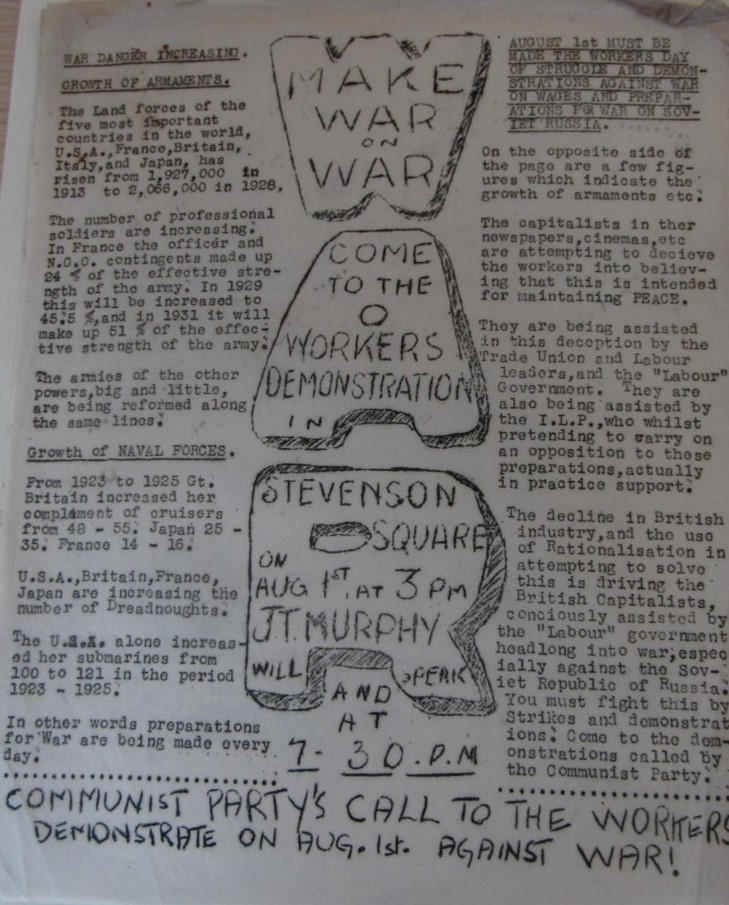

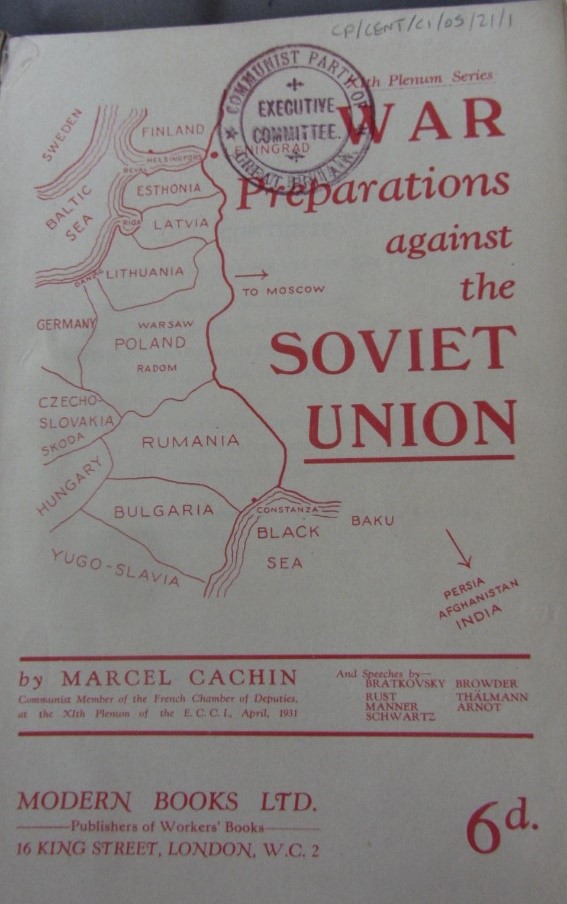

I examined material related to the CPGB’s anti-militarist campaigns at a variety of archives. Documents at the People’s History Museum helped me to propound my theory that the removal of the original leadership in 1929, epitomised by the replacement of General Secretary Albert Inkpin, was in part due to Moscow’s dissatisfaction with the Party’s sluggish anti-war propaganda. Numerous documents suggested that British communists shared ‘widespread disbelief in the immediate danger of war’ with the Soviet Union in 1927, instead prioritising the threat to China following the dispatch of British troops to Shanghai earlier that year.[2]

Further research at the National Archives confirmed a lack of attention to the threat of a Soviet war. Security services assumed that communist publications on the ‘war danger’ were referring solely to the situation ‘in China’,[3] and believed that any substantial propaganda dedicated to fighting the war danger against the Soviet Union began only after 1929, when Inkpin was removed.[4] Linking the replacement of the CPGB’s leadership to its anti-militarist campaigns therefore offers a new interpretation of a key event within the history of British communism.

Ultimately, embarking on these research trips has allowed me to further develop the key arguments within my thesis, and as I approach the completion of my PhD I feel a renewed confidence in my work as a result of these archive visits. I am grateful to the Society for the Study of Labour History for its financial support.

[1] CAC, DMAR/4/32, N.C.F. Trustees Annual Report January to December 1920, 2.

[2] PHM, CP/IND/CIRC/70/02, ‘Lessons of the Anti-War Campaign’ Letter to all CPGB Districts and Locals, 13th September 1929

[3] TNA, HO 144/9486, Home Office Letter ‘re. “Worker’s Life 12.8.27 “The Communist” August 1927’.

[4] TNA, KV 3/382, Memorandum: Communist Propaganda, 20th March 1933, 2.

James Squires is a PhD student at Sheffield Hallam University. He is researching the impact of First World War anti-militarism on the Communist Party of Great Britain during the 1920s

Find out more about bursaries on offer from the Society for the Study of Labour History.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.