The American historian William M Johnston talked in his book Celebrations about a ‘cult’ of anniversaries. And he noted how they provide an opportunity – or excuse – to mark the passage of time in ways that help communities to build and sustain a sense of identity. For many in the labour movement, there could be no bigger anniversary in 2024 than the centenary of the first Labour government – something we look at below. This year also marks the thirtieth anniversary of Labour Party leader John Smith’s death, the fortieth anniversary of the 1984-85 miners’ strike, and the sixtieth anniversary of Harold Wilson’s first Labour government. None of these events, however, are marked among the ten labour history anniversaries included here, for they fall outside the pattern of twenty-five-year steps back in time that we have used for the past three years. So in 2024, we look to…

1999: 25 years ago: Legal right to union recognition

1974: 50 years ago: Heath is out, Wilson back in

1949: 75 years ago: Dockers on strike

1924: 100 years go: First Labour government

1899: 125 years ago: Seats for shop assistants

1874: 150 years ago: Birth of women’s trade unionism

1849: 175 years ago: Cholera claims the lives of Chartists

1824: 200 years ago: Repeal of the Combination Acts

1799: 225 years ago: Pitt’s Combination Act in force

1774: 250 years ago: Birth of Spencean Arthur Thistlewood

1999: 25 years ago: Legal right to union recognition

The Employment Relations Act 1999 gave trade unions a legal right to be recognized by employers following a ballot and to bargain on behalf of workers over pay, working conditions, employee benefits and other rights. The Act also gave employees the right to be accompanied by a trade union official at disciplinary or grievance hearings, and introduced unpaid parental leave in addition to maternity leave. The Mirror hailed the legislation as ‘a Blair deal’ for parents and it was generally welcomed by trade unions, but Employment Secretary Stephen Byers received no more than polite applause when he spoke at the TUC Congress in Brighton that autumn – his appearance overshadowed by a row between the government and the Fire Brigades Union over the right to strike and proposals to scrap national pay bargaining.

Also in 1999, elections for the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly both end with Labour as the largest party but entering alliances with the Liberal Democrats to form majority administrations; a statutory National Minimum Wage comes into effect on 1 April at £3.60 for those over 21.

1974: 50 years ago: Heath is out, Wilson back in

1 January 1974 marked the start of the three-day week. Imposed by Ted Heath’s tottering Conservative government in the wake of a four-fold increase in crude oil prices and the likelihood of industrial action by the miners, it was one of a number of energy-saving initiatives that included a 50mph speed limit, heat limit of 63oF, and the desperate ‘switch off something’ campaign. After a ballot the National Union of Mineworkers set a strike date of 10 February in pursuit of its pay claim. But there was to be no strike, as Heath called a general election for 28 February that brought an end to the Conservatives’ industrial policy and returned a minority Labour government under Harold Wilson. In July 1974, Chancellor Denis Healey ended compulsory wage restraint and reintroduced food subsidies. The hated and already unworkable Industrial Relations Act was repealed and the miners’ dispute expensively settled. That October, Wilson went to the country again, emerging with an overall majority of three seats. Neither the social contract under which Labour had sought to govern the country, nor its majority in the Commons would endure long.

Also in 1974, the Local Government Act 1972 takes effect, creating six metropolitan counties and legally transferring Newport and Monmouthshire from England to Wales; power sharing in Northern Ireland collapses after a Unionist strike; the IRA bombs the Houses of Parliament, Tower of London, and pubs in Woolwich and Guildford used by off-duty soldiers.

1949: 75 years ago: Dockers on strike

Clement Attlee’s Labour government declared a state of emergency after more than 13,000 London dockers walked out in solidarity with a strike called by the Canadian Seamen’s Union. Amid accusations of a Communist conspiracy in both Canada and the UK, the strike was highly contentious: both the Transport and General Workers’ Union and the National Amalgamated Stevedores and Dockers unsuccessfully directed their members to return to work; and the Trades and Labour Congress of Canada suspended the seamen’s union for its refusal to end the strike. Attlee sent 11,000 servicemen into the docks to load and unload cargoes, while the dockers won support from TGWU members at Smithfield Market who threatened to refuse to handle meat unloaded from blacked ships. The four-week strike ended on 25 July, when London dockers voted unanimously by a show of hands for ‘an orderly return to work’ after their Canadian counterparts ended their dispute.

Also in 1949, Ireland Act recognizes the Republic of Ireland and guarantees Northern Ireland’s place in the UK as long as a majority want it; George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four published; Parliament Act cuts the House of Lords veto over legislation passed by the Commons to one year.

1924: 100 years ago: First Labour government

The General Election in December 1923 had resulted in a hung parliament, with the Conservatives under Stanley Baldwin taking 344 seats and Labour on 191 pushing the Liberals into third place. Having lost his mandate for protectionism, Baldwin resigned as prime minister and advised the king to send for the Labour leader Ramsay MacDonald. On 22 January, MacDonald formed the first, minority, Labour government. Though hamstrung by its lack of a majority, the government achieved a significant legislative victory in John Wheatley’s Housing Act, improved benefits for the unemployed and pensioners, and reintroduced a minimum wage for agricultural workers. In the face of a persistent ‘red scare’ campaign initiated by the Conservative and Liberal parties, MacDonald called a further election in October 1924. The party was dogged throughout the campaign by the Daily Mail’s publication of the ‘Zinoviev letter’ – a forged document released by the Foreign Office and allegedly written by the head of the Communist International urging socialists in Britain to prepare for violent revolution. Labour’s vote slumped and Liberal support at the polls collapsed, leading to Baldwin’s return with 412 seats against 151 (down 40) for Labour, and 40 (down 118) for the Liberals.

Also in 1924, Margaret Bondfield becomes the first woman to serve as a minister; birth of the historian E. P. Thompson on 3 February; death on 14 July of Isabella Ford, trade unionist involved in the Manningham Mills dispute and founder member of the Independent Labour Party in Leeds.

1899: 125 years ago: Seats for shop assistants

The life of the Victorian shop assistant was not an easy one. Those working in the big new department stores that had sprang up in town centres across the country were typically expected to live in dormitory-style accommodation on the premises as a condition of employment, where they were subject to oppressive rules and regulations, and had money deducted from already small salaries for their food and lodging. The Seats for Shop Assistants Act aimed to ameliorate one of the numerous hardships facing women shop workers in particular: the requirement to stand without break throughout their shift, which could run to twelve hours of more. The initiative to force employers to provide seats for their staff originated with the Glasgow Council for Women’s Trades, which succeeded in getting a private members’ Bill through the House of Commons. It was thrown out by the House of Lords, where it had been opposed by the Prime Minister, the Earl of Salisbury. A second Bill in the same year, introduced by the Duke of Westminster, passed both Houses despite continued government opposition, and became law, prescribing at least one seat for every three female employees and a fine of up to £3 for a first offence of failing to comply.

Also in 1899, General Federation of Trade Unions is founded at a special Congress of the TUC with the aim of creating a national strike fund that could be drawn upon by affiliated unions; National League of the Blind registered as a trade union – it lives on through the Community union; influential Liverpool councillor and MP Bessie Braddock born 24 September.

1874: 150 years ago: Birth of women’s trade unionism

Established on the initiative of Emma Paterson at a conference in July 1874, the Women’s Protective and Provident League was not in itself a trade union but a body for the promotion of trade unionism among women. In the years ahead, however, it would help to launch as many as thirty trade unions, and give women a formal voice in the trade union movement. Patterson, born in 1848, had worked briefly in bookbinding before becoming secretary of the Working Men’s Club and Institute Union at the age of nineteen. Visiting America on her honeymoon in 1873, she was inspired by the Women’s Typographical Society and the Female Umbrella Makers’ Union, and on her return to England wrote an article for Labour News advocating an association of women trade unionists. Paterson become the WPPL’s secretary and organizer, and would remain so until her death in 1886, but it was not the trade union she had wanted. Later in 1874 she helped form the Society of Women Employed in Bookbinding. Other unions followed, including the Society of London Sewing Machinists, the Dewsbury, Batley and Surrounding District Heavy Woollen Weavers’ Association, the Leeds Spinners’ Women’s Association and the Benefit Society for Glasgow Working Women. In 1875, Paterson and Edith Simcox became the first women delegates to attend the TUC Congress; and the following year, she and the WPPL would launch the Women’s Union Journal. Paterson died at the age of just 38, but the organisation she had founded endured, becoming the Women’s Trade Union League in 1890 and the women’s section of the TUC in 1921.

Also in 1874, Factory Act sets the minimum working age for children in textile factories and mills at nine, rising to ten a year later; ‘Revolt of the Field’ ends after two years with the defeat and near-bankrutpcy of the National Agricultural Labours’ Union

1849: 175 years ago: Cholera claims the lives of Chartists

The cholera epidemic that ripped through Britain and Ireland in 1849 hit hardest at the poor, whose poverty, insanitary living conditions and poor diet made them more susceptible. In England and Wales, it claimed the lives of 52,000 people, and not surprisingly took a major toll on working-class Chartists. Among those who died were the radical publisher and signatory to the People’s Charter Henry Hetherington, the Greenwich Chartist May Paris, the President of the Manchester Chartists George Smith, and Joseph Williams and Alexander Sharp, both Chartist prisoners in London’s Tothill Fields Bridewell. Though London was worst hit with 14,137 deaths, cholera also claimed 5,308 lives in the major port city of Liverpool from where it spread to the United States. In Ireland, where the population had been decimated by famine, cholera took another 30,000 lives, exacerbated by the forced return of Irish paupers from Scotland.

Also in 1849, Karl Marx moves from Paris to London, where he will make a new life with his family; Chartist leader Feargus O’Connor launches a further wave of petitioning based on local petitions, but succeeds in gathering just 53,816 signatures; corn laws abolished some three years after their repeal by an Act of 1846.

1824: 200 years ago: Repeal of the Combination Acts

William Pitt’s government had plunged trade unions into a long darkness. The historian of industrial relations Dr Dave Lyddon recently wrote: ‘The quarter-century of the main “Combination Acts” saw the triumph of laissez-faire in the labour market as the remaining Tudor (sixteenth century) wage-fixing and apprenticeship laws were repealed. Workers were now left to their own devices under rampant capitalism.’ But when repeal finally came, it was sudden and comprehensive. The social reformer Francis Place is credited with the successful campaign for repeal, working through Joseph Hume to persuade MPs into a volte face on twenty-five years of oppressive stability. But he did so in the belief that repeal would expose the futility of trade unions and make them less attractive to workers by placing workers’ and employers’ organisations on an equal footing. He could not have been more wrong. Repeal enabled unions to organise openly and act effectively in pursuit of their members’ interests without fear of criminal sanctions. Realising their mistake, MPs rapidly brought in fresh legislation in 1825 to reimpose criminal sanctions on picketing and other activities.

Also in 1824, the Mechanics Institute opens in Manchester; death of the parliamentary reformer Major John Cartwright, 23 September; Vagrancy Act makes it a criminal offence to beg or sleep rough, with penalties of up to one month in gaol.

1799: 225 years ago: Pitt’s Combination Act in force

William Pitt’s government passed the first of two Combination Acts intended to clamp down on nascent trade unions by making it illegal for workers to ‘combine’ against their employer for shorter hours or more pay. Though trade unions were already illegal under a swathe of legislation for particular industries, the 1799 and 1800 Acts applied generally and were quicker and easier to deploy, needing only a summary trial before two magistrates rather than a full hearing at the assizes. The laws had a chilling effect, but were used more often as a threat than as legal tool, and historians are divided on their effectiveness. E. P. Thompson argued in his Making of the English Working Class (1963) that, ‘By 1811 we can witness the simultaneous emergence of a new popular Radicalism and of a newly-militant trade unionism. In part, this was the product of new experiences, in part it was the inevitable response to the years of reaction.’ In A People’s History of England (1938), the historian A. L. Morton noted: ‘These laws were the work of Pitt and of his sanctimonious friend Wilberforce whose well known sympathy for the negro slave never prevented him from being the foremost apologist and champion of every act of tyranny in England, from the employment of Oliver the Spy or the illegal detention of poor prisoners in Cold Bath Fields gaol to the Peterloo massacre and the suspension of habeas corpus.’

Also in 1799, Unlawful Societies Act outlaws clandestine radical societies and require a printer’s imprint on all published material; James Watson, Owenite, Chartist and radical publisher, born 21 September.

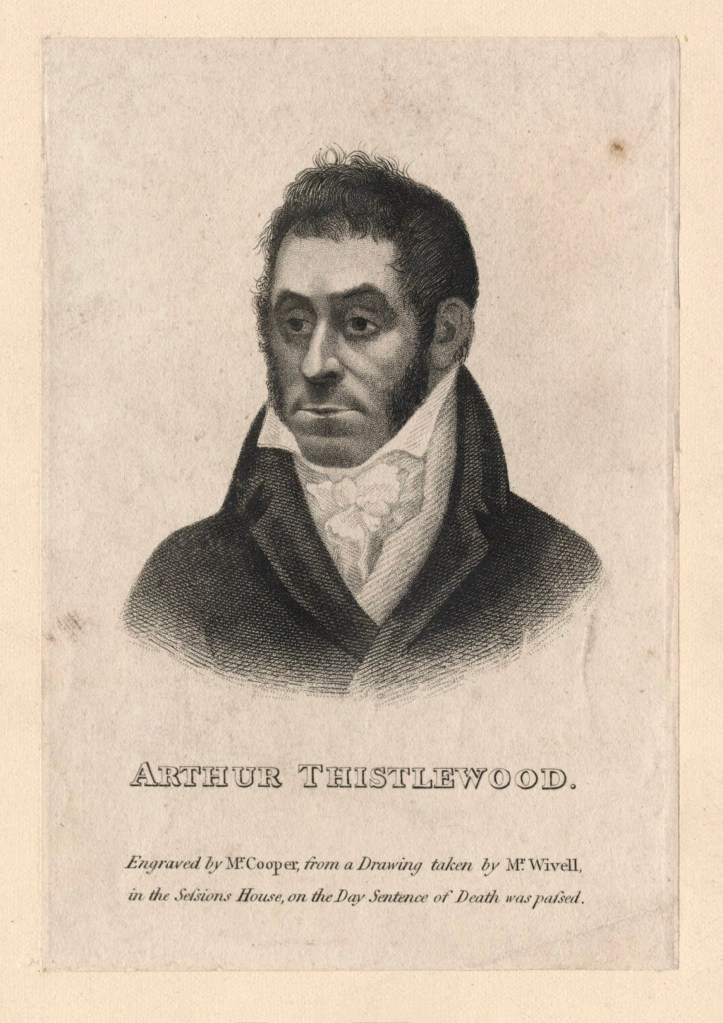

1774: 250 years ago: Birth of Spencean Arthur Thistlewood

Arthur Thistlewood was born on 1 May in Lincolnshire. After working as a land surveyor, serving in the army and attempting to farm, bought with the help of his father, he moved to London in 1811, where he became a member of the Society of Spencean Philanthropists, an ultra-radical group inspired by Thomas Spence, who had argued for common ownership of the land. In 1816, Spence and other members of the Society tried to use a meeting at Spa Fields addressed by ‘Orator’ Henry Hunt to spark a revolutionary uprising. The attempt failed, and Thistlewood was one of four men charged with high treason. The trial collapsed when a jury refused to find a true bill against one of the four. He was, however, gaoled in 1817 after challenging the prime minister, Lord Sidmouth, to a duel. Thistlewood was the leading figure in the Cato Street conspiracy in 1820, planning to capture and execute the prime minister as a prelude to revolution. A police spy betrayed the conspirators, and in the course of their arrest, Thistlewood killed a police officer. Eleven men were convicted of high treason; Thistlewood was one of five to be hanged and subsequently beheaded at Newgate.

Also in 1774, John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, publishes his pamphlet Thoughts Upon Slavery arguing against the slave trade.

Further reading

There have been few histories of the 1924 government, the best of which is Britain’s First Labour Government, by John Shepherd and Keith Laybourn (Palgrave Macmillan, 2006). It will soon be joined on the bookshelves by The Wild Men: The Remarkable Story of Britain’s First Labour Government (Bloomsbury Continuum, 2024) by David Torrance, constitutional specialist at the House of Commons Library, and by The Men of 1924: Britain’s First Labour Government (Haus Publishing, 2023) by Peter Clark. There are probably more books about Ramsay MacDonald than the government he first led, including the classic Ramsay MacDonald: A Biography (Jonathan Cape, 1977) by David Marquand, and Ramsay MacDonald (Haus Publishing, 2006) by Kevin Morgan.

There are numerous histories of trade unionism. One of the few that confidently spans the period from the imposition of the Combination Acts in the 1790s to the further imposition of restrictions on trade unions by the governments of Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s is Keith Laybourn’s A History of British Trade Unionism (Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 1992) which tells the story of trade unions from the 1770s to the end of the 1980s for a generalist reader.

Three hundred years of strikes: contours, legal frameworks, and tactics by Dave Lyddon is a long-term overview that gives both an overview of the continuities and breaks in UK industrial relations in the modern era and numerous examples of strikes and their place in the broader pattern of events. It is open access.

In Early Trade Unionism (Routledge, 2000), the later Malcolm Chase uncovered a history of trade unionism in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century that his often overlooked. With an emphasis on trade union mentality and ideology, rather than on institutional history, the book provides a critical focus on the politics of gender, on the demarcation of skill and on the role of the state in labour issues.

As an activist and later senior official in the Shop Assistants Union and its successors, P. C Hoffmann was able to write something of an insider account of shopworker trade unionism at the end of the nineteenth century and through the first half of the twentieth. They Also Serve: The Story of the Shop Worker (Porcupine Press, 1949) can be downloaded from the Union of Shop, Distributive and Allied Workers website as a PDF.

The papers of the Women’s Protective and Provident League can be found in the TUC Library Collections.

Histories of cholera in the mid-nineteenth century tend to focus on Dr John Snow’s discovery of the means by which it was transmitted and his removal of the handle from the water pump in Broad Street, London. You have only to google ‘John Snow cholera’ to find a wealth of material. There are accounts of the lives of Henry Hetherington, May Paris, Alexander Sharp and Joseph Williams on the Chartist Ancestors website. Local studies of the cholera epidemic include these for Sheffield, Lambeth and Mevagissey in Cornwall.

Conspiracy on Cato Street: A Tale of Liberty and Revolution in Regency London by Vic Gatrell, (Cambridge University Press, 2022), is an illuminating and highly readable account of the conspiracy and the conspirators. There is also a short account of the conspiracy on this website – see Cato Street: inside the building where London’s ultra radicals met their end.

See also

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.