Opening a website series on songs associated with labour history, John McIlroy looks at ‘The Working Class in Twentieth-Century Song: A Fan’s Notes[1]’ arguing that researching the genealogy of songs, finding new ones, rediscovering old ones, exploring the cultural ambience in which they were created and performed is part of the folklorist’s mission and the historian’s brief.

Find out more about this series.

Introduction

The Great American Song Book and the World of the Working Class

Rock ‘n’ Roll, Country, Love and Labour

The Swinging Sixties and Militant Seventies, Protest, Working-Class Heroes and Revolution

Punk Rock, Thatcher, Reagan, Anti-Racism and the Great Miners’ Strike

Folk Music, the Music of Labour?

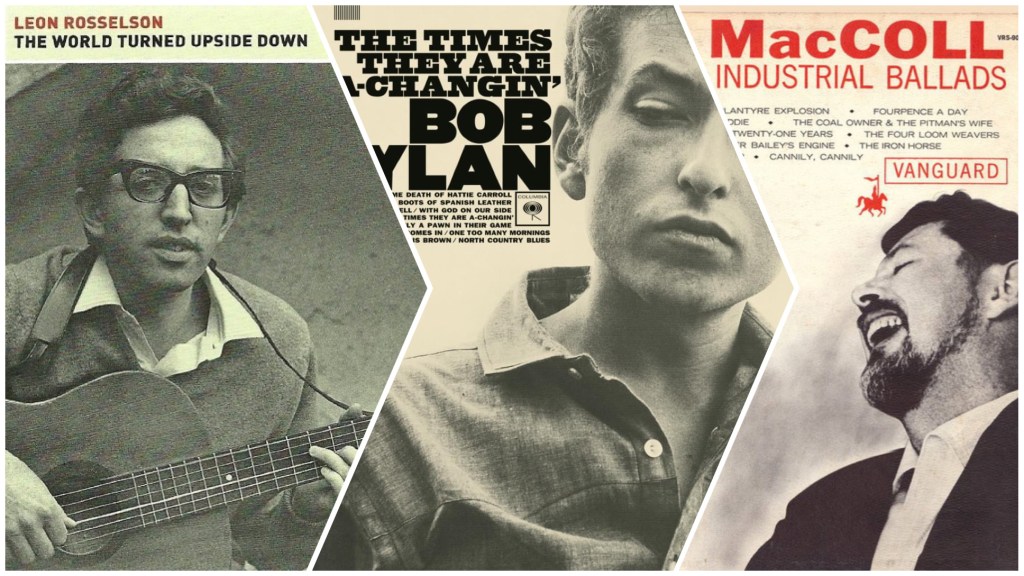

♫ Leon Rosselson, The World Turned Upside Down

♫ Ewan MacColl, Four Pence A Day

♫ Luke Kelly and The Dubliners, Dirty Old Town

♫ Brendan Behan, The Captains And The Kings

♫ Leon Rosselson, Palaces Of Gold

♫ Paul Brady, Arthur McBride And The Sergeant

♫ Ewan MacColl, The Shoals Of Herring

♫ Leon Rosselson, Tim McGuire

♫ The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem, Four Green Fields

♫ Bob Dylan, Only A Pawn In Their Game

Reflections

Introduction

Casual acquaintance with twentieth-century popular music will suggest that like Bessie Smith and Sophie Tucker’s Good Man, songs which reflect the concerns of labour history in any meaningful fashion are hard to find. Impressionistically at least, the past and present problems of workers, still less their endeavours to ameliorate and transform their position, seem to have been peripheral in the music of the twentieth century which reached a mass audience.[2] Context adds plausibility. In a capitalist society, whose powerholders are intent on prosecuting and preserving their interest in exploitation and the ideas necessary for its maintenance, music is a commodity created for profit. Production is controlled by the music publishing and record companies, radio, television, Hollywood, the British film studios, ‘the entertainment industry’. Privileging simplified lyrical and musical forms, catering for listening and dancing, the industry operates within the dominant ideology and appeals to mass audiences conditioned by it. That is not to say that songs subversive in one way or another of a mainstream which is never monolithic and rarely all encompassing in its reach, may not from time to time achieve a measure of popularity; or that producers are unaware of niche markets and the need to cater for minority tastes.

Fortunately, we can go beyond impressions: we have some evidence which enables us to gauge the popularity of songs, albeit by the crude index of sales, initially of sheet music and subsequently of single records. Established in the USA by 1940 and the UK from 1952, the record charts provide an imperfect but rough guide to what was popular over the years.[3] In the first part of this essay, I look at them in an attempt to provide a more evidenced, although far from comprehensive, overview of the extent to which songs about workers, their history and contemporary predicament and struggles – taken broadly – achieved a measure of popularity.[4] In the process, I say a word or two about the themes, subjects and musical trends that dominated the best sellers from the 1920s to the 1980s. The second part of the paper turns to look at a minority but possibly more fruitful field, folk music, and briefly explores whether it has redeemed the promise of its pioneers to recuperate and extend past traditions of workers’ song and help create a counterculture linked to social change in and beyond the labour movement.[5]

The Great American Song Book and the World of the Working Class

Twentieth-century popular song reflected the labour/leisure divide. It centred on the life-affirming, consolatory power of romantic love, typically represented as a prelude to happiness, monogamy and the nuclear family, or the unhappiness and loneliness occasioned by infidelity or bad luck. Songs like Walter Donaldson and George Whiting’s My Blue Heaven – ‘Just Molly and me/And baby makes three’ –Kalmar, Ruby and Snyder’s Who’s Sorry Now? – ‘whose heart is aching for breaking each vow’ – or Buck Ram’s Twilight Time – ‘Each day I pray for evening just to be with you/Together once more at Twilight Time’ – endured into the age of rock ‘n’ roll, when they were hits for Fats Domino, Connie Francis, the Platters, and beyond. In the wonderful world of wax, life moved unproblematically from the wedding ceremony in Von Tilzer and Fleeson’s Apple Blossom Time – for as Cahn and Van Heusen were telling us a little anachronistically in 1956, Love And Marriage went together like a horse and carriage – to the domestic, gendered idyll of Rodgers and Hart’s Mountain Greenery –

And if you’re good

I’ll search for wood

So you can cook

While I stand looking

Occasionally, usually humorously, the world outside intruded. Donaldson and Gus Kahn’s Makin’ Whoopee rehearsed the difficulties of marriage and the journey from church to divorce court, highlighting the institution’s economic basis. When the dream disintegrated, as in Larry Conley and Willard Robison’s Cottage For Sale – lines like ‘the lawn we were proud of is turning to hay’ were emoted down the years by a long line of minstrels from Billy Eckstine to Willie Nelson – resilience was required. Casualties were urged by Dorothy Fields and Jerome Kern to ‘pick yourself up, dust yourself down and start all over again’. This demanded, as Johnny Mercer insisted, an ability to ‘accentuate the positive’ in the knowledge that, as Al Jolson declaimed, ‘You can’t have everything’. Nor should you want to. As the millionaire Cole Porter evinced in Who Wants To Be A Millionaire, ‘…I don’t. Cause all I want is you.’ But you could always have a good time. Happiness was not contingent on cash, as Kahn pointed out in his saga of ‘the Roaring Twenties’.

Every morning, every evening

Ain’t we got fun

Not much money

Oh but honey

Ain’t we got fun

There’s nothing surer

The rich get rich and the poor get poorer

In the meantime

In between time

Ain’t we got fun.[6]

If the message did not always get through, on the whole it reinforced most workers’ intuition that there was little alternative: you had to accept things as they were, get on with it, make the best of the hand fate had dealt you and enjoy what you have while you can. Russ Morgan’s hardy perennial, You’re Nobody Till Somebody Loves You put matters plainly: ‘The world is the same, you’ll never change it – so find somebody to love’. You could sometimes take refuge in a cosmeticized, brief, rarely white, Christmas. Or, as the century wore on, escape to Faraway Places with strange sounding names or accept Mercer’s invitation: Dream ‘when you’re feeling blue/Dream that’s the thing to do’. Or turn to drink, as he did in One For My Baby ‘… and one more for the road’. If you were rich, pampered and bored you might console yourself with thoughts of downward social mobility among Ruritanian labourers as in Cole Porter’s final offering:

Wouldn’t it be pleasant

To be a simple peasant

And spend a happy day digging a ditch[7]

Escape was temporary. All too often, as Jolson and Billie Holliday pointed out:

You’ll come weary at heart

Back where you started from

The bird with feathers of blue is waiting for you

Back in your own backyard.[8]

Labour, class conflict, inequality, politics, barely impinged. Love, its joys, trials and tribulations were at the heart of ‘The Great American Songbook’. Usually identified with the Gershwins; Jerome Kern; Cole Porter; Rodgers and Hart; Donaldson and Kahn; Schwarz and Dietz; Johnny Mercer; Hoagy Carmichael; Harry Warren and Al Dubin, among others, it dominated the first half of the musical century in both America and Britain, surrounded by a mass of songs in similar mould, if frequently more transient. It constituted a significant cultural achievement of the European diaspora and the American melting pot. These lyricists and composers often came from impoverished immigrant backgrounds. They were blessed with talented interpreters who drew on the jazz tradition of black music: Holliday; Frank Sinatra; Bing Crosby; Ella Fitzgerald; Nat Cole; Sarah Vaughan; Peggy Lee.

As would become the norm in much popular culture, British songwriters such as Noel Coward, Ray Noble, Eric Maschwitz, Jimmy Kennedy and Michael Carr, and their imitators, followed the American prescription. Some such as Coward and Ronald Frankau pursued the path of light satire in songs like Mad Dogs And Englishmen, Good Times Are Just Around The Corner and Let’s Not Be Beastly To The Germans. And on both sides of the Atlantic, there was no problem with contributing propaganda when the country was threatened by war. Al Bowlly and Tommy Handley offered songs lampooning Hitler, Kennedy and Carr’s We’re Going To Hang Out The Washing On The Siegfried Line briefly threatened to become the Tipperary of World War II, and Irving Berlin contributed This Is The Army Mr Jones and My British Buddy. There was bellicosity as in Praise The Lord And Pass The Ammunition and paeans to productivity like The Five O’Clock Whistle. But love endured with A Pair Of Silver Wings, I Walk Alone, We’ll Meet Again, Somewhere in France With You, Room 409 and That Lovely Weekend.

Other traditions – Vaudeville in the USA and Music Hall in Britain – were alive and kicking, if declining, in the first fifty years of the century. Music hall songs dealt directly, albeit usually in a light-hearted and stoic way, with the vicissitudes of working-class experience. Marie Lloyd’s Follow The Van extracted humour from a moonlight flit. Leslie Sarony’s Ain’t It Grand To Be Bloomin’ Well Dead! – later adapted as a protest song by the Clancy Brothers and Joan Baez – insisted nobody really cared about you once you were no longer around. Where for Rodgers and Hart the First of May, rather than being Labour Day, was an occasion for escape – ‘Spring is here, so blow your job/Throw your job away’ – lack of work could be a calamity for wage slaves. In Wait Until The Work Comes Round – still being sung in folk clubs by Bob Davenport in the 1960s – Gus Elen recommended accepting the cyclical ‘ups and downs’ of capitalist economics, looking on the bright side of life, making the best of a bad job and enjoying the opportunities of enforced leisure unemployment provided:

What’s the use of kicking up a row

If there ain’t no work about?

If you can’t get a job, you can rest in bed

Till the school kids all comes out

If you can’t get work you can’t get the sack

That’s an argument that’s sensible and sound

Lay your head back on yer piller and read yer Daily Mirrer

And wait till the work comes round

In Herbert Rule and Fred Holt’s brilliantly understated Only A Working Man, Lily Morris reminded her audiences that women also worked and laboured under a double burden. In a sarcastic evocation of the ideal marriage, she reflected:

I wake him every mornin’ when the clock strikes eight

I’m always punctual and never late

With a nice cup o’ tea and a little round of toast

The Sporting Life and The Winning Post

I make him nice and cosy, then I toddle off to work

I do the best I can

For I’m only doing what a woman should do,

Cause he’s only a working man!

If, in the Tin Pan Alley ‘moon and June’ canon, fulfilment lay in the private sphere of ‘boy meets girl, boy marries girl’ and social issues rarely intruded, there were always exceptions. They were limited in scope and subject matter. Like Cole Porter’s Love For Sale, such songs usually related to popular music’s overriding concern. And things had to be kept within respectable bounds. After a storm of scandal over ‘appetising young love for sale’, Porter engineered a compromise and switched the ethnicity of the prostitute from white to black. Gloomy Sunday, immortalised by Billie Holliday, seems at first listening to centre on a suicide; listened to more attentively it was, as so often, all a dream. Yip Harburg and Jay Gorney’s Brother Can You Spare A Dime? – ‘Once I built a railroad, I made it run/Made it race against time/Once I built a railroad now it’s done’ – entered the popular imagination in America and Britain via Crosby, Rudy Vallee and Al Bowlly as a remonstrance against productive workers thrown on the scrap heap in the 1930s depression. In similar vein, Joan Blondell sang Remember My Forgotten Man in Gold Diggers of 1933. Harburg was a gifted lyricist, a member of the American Socialist Party blacklisted, despite his anti-Communism, in the 1950s. Despite excision of the introductory verse, ‘When the world is in a hopeless jumble …’ from the film of The Wizard of Oz (1938), Over The Rainbow is a song of hope and yearning for a better world. It is stretching things a little to give it the socialist – still less Zionist – subtext some have attributed to it.

Others have celebrated Sinatra as a leftist in the 1940s.[9] The musical evidence seems to be his recording of The House I Live In composed by the Black Communist activist Earl Robinson, who wrote the tune to I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night. Sinatra’s representation of a rose-coloured, idealised ‘land of the free’ came at the tail end of the radical Popular Frontist strand in the narrative of the New Deal-wartime national unity. It was isolated and untypical of his output of the period. But, sandwiched between his far bigger hits Nancy With The Laughing Eyes and the No. 1 Oh What It Seemed To Be, the song reached No. 22 on the infant US charts.

Frankie Laine’s 1949 success, That Lucky Old Sun –

Up in the morning

Out on the job

Work like the devil for my pay

But that lucky old sun got nothin’ to do

But roll around heaven all day

– has been interpreted as metaphorising the oppression of the worker and privilege of the rich. It is more persuasively read as a plea to the Lord for release from worldly suffering and heavenly salvation. With Burton Lane, Harburg contributed songs like When The Idle Poor Become The Idle Rich to the 1947 musical Finian’s Rainbow which took up exploitation and racism in America and was filmed two decades later starring Fred Astaire and Petula Clark. The 1954 musical The Pajama Game, with a score by Richard Adler and Jeremy Ross, filmed in 1957 with Doris Day as the heroine, was described by Jean-Luc Goddard as ‘the first left-wing operetta’. A tale of attempts to deny workers a wage increase and break the union, ends happily as Day, an unusual workers’ representative, falls head over heels in love with the boss. Love conquers all, even class conflict. Even the hit songs, Hernando’s Hideaway and Hey There were in conventional mould.

In January 1956 every delivery boy was singing as he parked his bike:

You load 16 tons, what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt

St. Peter, don’t you call me ‘cause I can’t go

I owe my soul to the company store

Sixteen Tons had been written in 1946 by a young Kentucky country and western singer, Merle Travis, who also wrote Dark As A Dungeon Down In The Mine and Tex Williams’s Smoke! Smoke! Smoke! (That Cigarette). Hardly a critique of industrial capitalism, Sixteen Tons lamented the plight of the overworked, underpaid miner but celebrated him as one tough hombre. Sung by Tennessee Ernie Ford, it reached No.1 in Britain with a version by Frankie Laine at No.11. Singles also appeared by Michael Holliday, Ted Hockridge, Edmundo Ros and Ewan MacColl. Max Bygraves typically unimaginatively parodied it as Seventeen Tons. Few who bought the record seemed unduly concerned at the conditions of the miners or the operation of the Truck Acts. But the song was swiftly incorporated, mostly with a touch of humour, into the braggadocio of the young UK male:

If you see me comin’, better step aside

A lotta men didn’t, a lotta men died

Its appeal was enduring. Among those who subsequently recorded it were Eric Burdon, Johnny Cash and Tom Jones and, more incongruously, Bo Diddley and The Platters.[10]

Rock ‘n’ Roll, Country, Love and Labour

‘Rock ‘n’ Roll’ was, as Nik Cohn wrote, ‘very simple music. All that mattered was the noise it made, its drive its aggression, its newness’.[11] But there were elements of continuity. Single records often had one side for dancing and one side for dreaming or smooching. Of the wild men of 1956 and 1957, from the start of his career Elvis Presley recorded older ballads like That’s When Your Heartaches Begin and I Love You Because; Little Richard revived By The Light Of The Silvery Moon and Babyface; Fats Domino sang Louis Armstrong’s Blueberry Hill and Bing Crosby’s Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? But like its predecessors, the new genre had little to say about the world of work – even Buddy Holly’s Midnight Shift turned out to be about a goodtime gal or perhaps what today would be termed, less felicitously, ‘a sex worker’.[12] Frankie Lymon, Eddie Cochran and Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller – in a series of songs for The Coasters – explored the world of adolescence. From 1958, rock lost its rawness, and Frankie Avalon, Sam Cooke, Dion and the Belmonts and even Chuck Berry, apart from a slight brush with employment and work in a filling station in Too Much Monkey Business, concerned themselves with the angst of youth and problems with parents, with schools, cars, loneliness and love. Elvis’s rough edges – ‘If you’re looking for trouble/ You came to the right place’ – and raw sexuality were refined – his cover of Smiley Lewis’s One Night Of Sin became One Night With You. High school and the age of ‘the Bobbies’ – Darin, Rydell and Vee, and in Britain Cliff Richard, Adam Faith and Billy Fury, dawned. As Tin Pan Alley morphed into the Brill Building, the tunesmiths of the early 1960s – Pomus and Shuman; Bacharach and David; Goffin and King; Sedaka and Greenfield; and Mann and Weil – adapted its time-honoured formulas to the new teenage market for 45 rpm. records.

The ‘do-it-yourself’ music of the skiffle boom should not be overlooked. But it was a brief affair. It was largely confined to 1956 and 1957, which saw hits by Johnny Duncan, notably Last Train To San Fernando (No.2 UK, 1957) and Nancy Whiskey with the Charles McDevitt Skiffle Group’s Freight Train (No.5 UK, 1957) and Greenback Dollar ((No.28 UK, 1957). It brought American folk music to a wider audience, particularly through the pyrotechnics of ‘the King of Skiffle’, Lonnie Donegan, whose chart success lasted until 1962. He sang about work (Rock Island Line, No.8 UK, No.8 US, 1956) and work songs (Pick A Bale of Cotton, No.11 UK, 1962), about The Grand Coulee Dam (No.6 UK, 1958), Fort Worth Jail (No.14 UK, 1959) and the Battle of New Orleans (No.2 UK,1959), even murder and hanging (Tom Dooley, No.3 UK, 1958). Donegan’s hits appropriated, popularised and made money from the work of pioneers like Huddie Leadbetter and Woody Guthrie. Other hits like My Old Man’s A Dustman (No.1 UK, 1960) had more to do with music hall comedy than work. Skiffle at best touched on real people and influenced future rock stars and folk singers.

Such partial exceptions to the amatory narratives were few and far between and usually unenlightening In 1960, few listeners took Sam Cooke’s Chain Gang (No.2 US, No.9 UK), with its rattling chains and mesmeric ‘Ooh …Aah’ backdrop, as an indictment of the prison system in the American South rather than an excellent pop song.[13] Sam had to wait until 1965 to succeed with his memorable protest A Change Is Gonna Come, and then as the B-side of his posthumous US top ten dance hit, Shake. In 1961, country singer Jimmy Dean (no relation) reached No.1 in the US, No.2 in the UK, with a song – and a voice – reminiscent of Tennessee Ernie Ford. Big Bad John again celebrated the masculinity but also the nobility and solidarity of the miner.

Every mornin’ at the mine you could see him arrive

He stood six foot six and weighed two forty five

Kinda broad at the shoulder and narrow at the hip

And everybody knew, ya didn’t give no lip to Big John

On a fatal day, the timbers gave way: ‘everybody thought they had breathed their last – ’cept John’. The doomed giant heroically holds up the roof while his fellow miners escape. It was the end of that ‘worthless pit’ but a marble stone remains, commemorating ‘one hell of a man’.[14] As Big Bad John slipped down the charts, to be succeeded in the USA by a number of parodies and a new No.1, The Marvelletes’ Please Mr Postman – a love-lorn plea for faster delivery by Detroit mail carriers, life for the miners and the rest of us went on as before. And in the way of the world, a sanitised version of Big Bad John turned up years later in adverts for Sainsbury’s and Domestos.

Despite its roots in folk music and relative closeness to the communities it catered for, country and western’s staple diet remained the ‘somebody did somebody wrong song’. Gene Autry’s Back In The Saddle Again, D. J. O’Malley’s When The Work Is Done Next Fall and other cowboy songs referred to work incidentally as a backdrop to people and places. Country’s poet laureate, ‘the hillbilly Shakespeare’, Hank Williams, like the pioneering Jimmie Rodgers, wrote about trucks and trains but generally about the pain of love and loneliness. In the early 1950s, proto-feminism, which remained very much a minority trend, was aired in Kitty Wells’ It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels, a reply to the Hank Thompson hit, The Wild Side Of Life. In the 1960s, Mel Tillis wrote Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love To Town, about the impact of war and maimed bodies on sexual relations. After leaving Sun Records, Johnny Cash recorded a series of albums, Songs Of Our Soil, Blood, Sweat And Tears and Bitter Tears – Songs Of The American Indian, about blue-collar America and the dispossessed, which included songs like With These Working Man’s Hands and The Ballad Of Ira Hayes. Through the 1960s and into the 1970s, Loretta Lynn’s Coalminer’s Daughter and Bobby Bare’s Detroit City portrayed industrial life with pride and disillusion, and David Allan Coe’s Take This Job And Shove It – made famous by the ironically named Johnny Paycheck – with defiance. While Cash purveyed an individualistic brand of rebelliousness, Merle Haggard expressed the social conservatism of redneck culture in Okie From Muskogee and The Fighting Side Of Me.

The Swinging Sixties and Militant Seventies, Protest, Working-Class Heroes and Revolution

In 1965, ‘Protest’ arrived in the British charts, powered by changing political and social trends and the influence of the burgeoning American folksong scene. More specific was the impact of the songs of Bob Dylan, hitherto confined to albums but popularised by Peter, Paul and Mary – on British bands searching for an alternative to covering US rhythm and blues hits. An early example was The Searchers’ recording of the former US Communist Malvina Reynolds’ anti-nuclear What Have They Done To The Rain (No.29 US, No.14 UK, 1965), while Peter, Paul and Mary had already had singles success with Blowin’ In The Wind (No. 2 US, 1963, No.14 UK, 1963) and a small British hit with The Times They Are A-Changin’ (No.44 UK, 1963). Released as a single, Dylan’s own version of the latter entered the British Top Ten in Spring 1965 (No.9 UK, 1965). Far from his best song in the genre, it saluted an irresistible tide of impending social transformation in which in Biblical terms the first would soon be the last. Dylan exhorted parents, Senators and Congressmen to heed the call, join the crusade or get out of the way ‘for the times, they are a-changin’.

It was followed by Dylan’s Chuck Berry influenced manual for the hip out on the street, Subterranean Homesick Blues (No.39 US, No.6 UK, 1965); Manfred Mann featuring Dylan’s With God On Our Side on the One In The Middle EP (No.6 UK, 1965), which satirised the official US version of its warlike history; Joan Baez’s version of Phil Ochs’s There But For Fortune (No.7 UK, 1965); and Donovan’s cover of Buffy St Marie’s The Universal Soldier (No.20 UK, 1965). The Animals weighed in with a plea for social mobility, We Gotta Get Out Of This Place, written by Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, who had graduated from efforts like Who Put the Bomp and You’ve Lost that Lovin Feeling to more social and currently lucrative themes.[15] Protest climaxed in Britain that Autumn with Barry McGuire’s Eve Of Destruction (No.4 UK, 1965) – ‘Think of all the hate there is in Red China/Take a look around at Selma Alabama’; and Sonny Bono’s ode to privileged self-pity, Laugh At Me (No.10 UK, 1965). The band-wagoning Hollies’ Too Many People, which combined criticism of the H-bomb and over-population, proved a step too far. Decline was sealed with the failure of the chameleon-like Bobby Darin, who had moved with effortless success from rock ‘n’ roll to Sinatra-style swing to rhythm ‘n’ blues and country, to dent the charts with perhaps the ultimate complaint, We Didn’t Ask To Be Brought Here Anyway.

The protest boom dealt effectively with, or trivialised, important political issues. The working class, still less the labour movement, scarcely got a look in. The Rolling Stones’s Salt Of The Earth contrived to laud its virtues a trifle inauthentically. Street Fighting Man (1967, No.17 UK, 1971) inspired by the anti-Vietnam demonstrations, had the whiff of radical chic about it. In contrast, Ray Davies’ songs for The Kinks frequently portrayed a forgotten section of the working class, trapped in poverty, for whom ‘the swinging sixties’ had never happened (Dead End Street, No.8 UK, 1966). Autumn Almanac (No.5 UK, 1967) celebrated a conservative, backward-looking, still-cherished but now ageing – ‘Oh, my poor rheumatic back’ – culture.

I like my football on a Saturday

Roast beef on Sundays, all right

I go to Blackpool for my holidays

Sit in the open sunlight

…

This is my street and I’m never gonna leave it

Davies’ songs were infused with nostalgia and romanticised memories of the corporate working class of the 1930s:

She’s bought a hat like Princess Marina’s

To wear at all her social affairs

She wears it when she’s cleaning the windows

She wears it when she’s cleaning the stairs

…

He’s bought a hat like Anthony Eden

Because it makes him feel like a lord

Despite the innovations of the 1960s, the old world remained resilient and personal predicaments remained at the heart of popular song. But wider change influenced the music. ‘Flower Power’ had its roots among the proponents of peaceful protest and passive resistance against the war in Vietnam – ‘the flower is more powerful than the gun’. It radiated out and became identified with the Hippies and belief the best way to change society was to change oneself through ‘a revolution of the mind’, sometimes facilitated by drugs. Flower Power’s best known base was the Haight Ashbury communes in San Francisco – also frequented by rock stars – and the philosophy was celebrated in Scott McKenzie’s major hit, San Francisco (Be Sure To Wear Flowers In Your Hair) (No.4 US, No.1 UK, 1967). Britain produced its own kitsch variant in the shape of The Flower Pot Men’s Let’s Go To San Francisco (No.4 UK, 1967) and the more serious but derivative San Franciscan Nights (No.9 US, No.11 UK, 1967) by Eric Burdon and the Animals. Love was now universalised as a social rather than individual relation, a cure for all society’s ills in The Beatles All You Need Is Love (No.1 US, No.1 UK, 1967). Yet the year ended with conventional fodder, Engelbert Humperdinck’s The Last Waltz and The Foundations, Baby, Now That I’ve Found You, firmly at the top of the pops. Vestiges of the Flower Power revolution lingered, but Thunderclap Newman’s Something In The Air (No.39 US, No.1 UK, 1969) summed up its sentiments and signalled its swansong:

Call out the instigators

Because there’s something in the air

We’ve got to get together sooner or later

Because the revolution’s here

The ferment in America’s black ghettoes at the end of the decade spilled over into the recording studios, produced songs like The Temptations’ Ball Of Confusion (No.7 UK, No.1 US, 1970) and linked up with the Anti-Vietnam War Movement in Edwin Starr’s War (No.1 US, No.2 UK, 1970): ‘War – What is it good for/ Absolutely nothin’!’.

The engagement of The Beatles, who in many ways embodied the decade, with wider social issues was belated and mediated by excursions into LSD and mysticism. Tracks like Nowhere Man and Taxman were trite, She’s Leaving Home and Eleanor Rigby superior, but while John Lennon’s You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away and Norwegian Wood reflected the influence of Dylan, they were still within the ‘private’ problematic. In 1968, the then doyen of cultural radicalism, Jean-Luc Goddard, described The Beatles as ‘apolitical’ and, as if in confirmation, Lennon’s Revolution, the B-side of Hey Jude, explicitly rejected the possibilities of the Euro-Maoism espoused by the French film director. Its sentiments provoked outcry on the left as ‘a petit-bourgeois cry of fear’, and an answer song by Nina Simone.

A year later, Lennon changed his mind and released two contagious anthems, Give Peace A Chance (No.2 UK, No.14 US, 1969) and Power to the People (No.6 UK, No.11 US, 1971). The former was adopted by protesters and sung by almost half a million people at an anti-Vietnam demonstration in Washington. Inspired by the marches against Edward Heath’s Industrial Relations Act, the latter was a hymn to the ‘instant revolution’ espoused, often unthinkingly, by the cultural avant-garde:

Say you want a revolution

We better get it on right away

Well you get on your feet

Head out to the street

…

Singing power to the people

… Power to the people, right on!

Lennon continued to write in similar vein with Gimme Some Truth, Imagine (No.3 US, 1971; No.5 UK, 1975; No.1 UK, 1980), Happy Christmas (War Is Over), (No.4 UK, 1972) and Working Class Hero. Imagine’s utopian sentiments were quickly assimilated by the mainstream, and it was soon being warbled by Diana Ross and a host of practitioners of ‘easy listening’. Working Class Hero remains relevant as a bleak, bitter denunciation of the repressive conditioning of mid-century capitalism:

They hurt you at home and they hurt you at school

They hate you if you’re clever and they despise a fool

Till you’re so fucking crazy you can’t follow their rules

A working class hero is something to be

Lennon described it as ‘a revolutionary song’; but while its sentiments transcended individual angst, there was no note of resistance or real-world revolution. Unlike most rock stars, he was active in radical causes, briefly in Britain and particularly in America in the early 1970s, attracting the attention of Nixon and the FBI, and his concerns were reflected in songs such as The Luck Of The Irish and Woman Is The Nigger Of The World (No.55 US, 1972) from the Somewhere In New York City album. Somewhat incongruously, Paul McCartney, who had been alarmed at Lennon’s overt political stance, followed suit. Despite being banned by the BBC, Give Ireland Back To The Irish reached No.13 in the British charts in 1972.

The increasing prominence of trade unionism in the 1960s and 1970s went largely unremarked by rock artistes, although The Kinks contributed an anti-union protest, Get Back In Line on a 1970 album. The song, like the Boulting Brothers film, I’m All Right Jack, was motivated by the job controls of the workers in the entertainment industry, in this case in America. In a song which fed into the right-wing narrative of ‘restrictive practices’, Ray Davies petulantly explained, ‘All I want to do is make some money’, and worried about whether he would be able to go to work that day:

Cause when I see the union man walking down the street

He’s the man who decides if I live or I die, if I starve or I eat

The industrial militancy of the period was reflected in record sales when The Strawbs’ Part Of The Union became a No.1 hit the following year. Despite claims it offered an anti-union discourse, the band stated it was intended to be supportive of what was happening on shopfloors across the country. However, the ability of capitalism to turn any challenge to its own advantage was illustrated in later years when the catchy chorus was adapted to headline adverts for the Norwich Union Insurance Company, airbrushing sentiments such as ‘I always get my way, If I strike for better pay’ from the messaging. Like so much British popular culture, the only song about trade unionism to make the charts possessed an American pedigree. The chorus, ‘You don’t get me I’m part of the union/Until the day I die’, bore a striking resemblance to Woody Guthrie’s Union Maid: ‘You don’t scare me, I’m sticking to the union, till the day I die’. In contrast to Guthrie’s song, at a time when it was still conventional, although the gender balance in unions was changing, the Strawbs were resolutely masculine: ‘Now I’m a union man/Amazed at what I am…’.[16]

Labour history put in a rare appearance in the Top Ten in the shape of Alan Price’s Jarrow Song (No.4 UK, 1974). Price, who had made a fortune copywriting the arrangement of the million-selling The House of the Rising Sun to the chagrin of his fellow Animals, who claimed equal authorship, commemorated the Jarrow Marchers of the 1930s. His song had a rousing tune, complete with brass band and infectious chorus, and its generally unimpressive lyrics added a radical twist as the wife counsels her departing husband:

And if they don’t give us half a chance

Don’t even give a second glance

Then Geordie with my blessing burn them down

Punk Rock, Thatcher, Reagan, Anti-Racism and the Great Miners’ Strike

Commentators have explained the advent of punk rock in 1976 in a variety of ways from a new generation’s alienation from the excesses of bloated supergroups performing ‘concept’ albums inaudibly in giant stadiums and increasingly part of the establishment, to the mood of social crisis and disillusion with things as they were as the postwar economic and political settlement came under strain. The music returned to basics. Often primitive lyrics, delivered in stridently working-class accents, conveyed a mood of confusion and chaos:

Oh I am an Anti-Christ

And I am an anarchist

Don’t know what I want

But I know how to get it

(The Sex Pistols, Anarchy In The UK, No.38 UK, 1976)

The Sex Pistols erupted into Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee celebrations in the summer of 1977 with an antidote to the orchestrated frenzy of adulation of Britain’s profoundly anti-democratic constitution:

God Save the Queen

She ain’t no human being

There is no failure

In England’s dreaming

It was a considerable distance away from the carefully crafted work of the Gershwins, Rodgers and Hart, Bob Dylan – or The Beatles. In its pristine energy, it emulated and exceeded the rebellious drive of rock ‘n’ roll and Merseybeat and the amateur élan of skiffle. Crucially, it resonated with sections of the youth: predictably banned by the BBC, God Save The Queen still reached No.2 in the charts. The Pistols laced media interviews with obscenity: their television confrontation with Bill Grundy in December 1976 scandalised ‘public opinion’ yet was admired by many young workers. Their music was driven by blasting guitars and thudding drums but perhaps their best realised parody was the Sid Vicious deconstruction of My Way, the self-congratulatory anthem taken from the French by Paul Anka and popularised by Sinatra, Presley as well as a multitude of working-class men with too many Saturday night drinks under their belts. They were courted without success by the left and right. Possibly the nearest they came to the world of work in this period was observing and sometimes defying the efforts of their manager, Malcolm McLaren, a contemporary variant on Larry Parnes and Andrew Loog Oldham, to garner publicity. So far as can be discerned, their only brush with the labour movement occurred when female workers at the EMI plant in Hayes, West London, refused to pack copies of Anarchy In The UK.[17]

Inspired by the Pistols, The Clash, whose success continued into the 1980s, evoked violence, riot and struggle against the police in a series of singles including White Riot (No.38 UK, 1977); (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais (No.20 UK, 1978); Tommy Gun (No.19 UK, 1978); the old Crickets/Bobby Fuller song, I Fought The Law (No.17 UK, 1979); and The English Civil War (No.25 UK, 1979). The latter was taken as a warning about the rise of the National Front, Tommy Gun a disquisition on contemporary terrorism. Exactly what was being said in lyrics which were at times opaque and susceptible to different interpretations, was not always apparent. More substantial than The Pistols, The Clash identified with the left and participated in ‘Rock Against Racism’, the organisation launched by the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) in 1976, as well as later initiatives.

Eton Rifles (No.2 UK, 1979) was the best of the early hits by The Jam and their gifted singer/songwriter Paul Weller. It was sparked by a news story that ‘Right To Work’ marchers passing Eton College had been jeered by its pupils. The song narrated an ensuing fracas between the public schoolboys and local working-class youth in which the forces of the proletariat were bested by the muscular resources – and ‘razor sharp wit’ – of the rugby playing, proto-officer corps. It constituted a prescient parable of what was to come and foreshadowed ruling class ability to successfully mobilise in the struggles of the ensuing decade. In Town Called Malice (No.1 UK, 1982) – a counterpart to The Specials Ghost Town (No.1 UK, 1981) which evoked the desolation that recession and unemployment was breeding in Britain’s cities – and particularly in Going Underground (No.1 UK, 1980), Weller was more forthright:

You choose your leaders and place your trust

As their lies wash you down and their promises rust

You’ll see kidney machines replaced by rockets and guns

And the public wants what the public gets

But I don’t get what this society wants

The early resistance to Thatcher’s project to dismantle the social democratic order, seed a 24/7 entrepreneurial culture and redraw the boundaries between life and work was marginally reflected in popular music. The Beat’s straight from the shoulder Stand Down Margaret (No.20 UK, 1980) and The Specials’ Rat Race (No.6 UK, 1980) rubbed shoulders with vacuous ditties like Dolly Parton’s 9 To 5 (No.1 US, 1980) and Sheena Easton’s different song of the same name (No.3 UK, 1980) in the Top Twenty listings. Most contemporary hits embraced traditional concerns. An impressive exception was Robert Wyatt’s Shipbuilding (No.35 UK, 1982), with world weary lyrics by Elvis Costello – ‘Within weeks they’ll be re-opening the shipyards/And notifying the next of kin once more’ – and music by Clive Langer. The song ruminated on a grim reality: the state’s devastation that government policies had wrought on traditional industries in Belfast, Merseyside and the North-East could only be remedied by re-arming for further destruction and the war over the Malvinas. Labour historians received a small credit when the LP, Life In The European Theatre, appeared in 1981 with tracks by, among others, The Clash, The Jam and The Undertones, royalties going to European Nuclear Disarmament and sleeve notes by Roger Deakin of Friends of the Earth and E. P. Thompson.

In the 1980s, the career of Bruce Springsteen took a new direction. His work fused rock and folk traditions in compelling stories which evoked the dilemmas of working-class life in the aftermath of Vietnam and the human consequences of America’s crumbling economy and de-industrialization. Springsteen attributed the new turn and concern with politics to the influence of Woody Guthrie and a growing preoccupation with how the past moulded the present, encouraged by reading books like Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States. The River (No.27 UK, 1980) and Hometown (No.5 UK, 1985; No.6 US, 1985) are good examples of the songs he wrote at this time. The former, one of Springsteen’s finest songs, sees love, happiness and hope culminate and collapse in pregnancy, early marriage and the protagonist’s abrupt and painful entry into the world of work:

… And for my nineteenth birthday

I got a union card and a wedding coat

…

I got a job, working construction

For the Johnstown Company

But lately there ain’t been much work

On account of the economy

The river once symbolised joy and optimism, washing away quotidian difficulties. It now mirrors pessimism as their lives darken:

Now all the things that seemed so important

Well, mister they vanished right into the air

Now I just act like I don’t remember

And Mary acts like she don’t care

They still go down to the river, but the river has run dry. The narrator muses:

Now those memories come back to haunt me

They haunt me like a curse

Is a dream a lie if it don’t come true

Or is it something worse

My Hometown describes the decline and fall of the area Springsteen grew up in, Freehold, New Jersey. A good place has turned bad, the factories and the mills have closed, racism has divided the workers. But the sense of belonging lingers. The exhilaration and Kerouac-like release in the excitement of moving on expressed in Springsteen’s 1975 Born To Run has evaporated. But as he leaves with his family in sober, considered flight, the protagonist repeats to his son what his father had told him long ago:

Son, take a good look around

This is your hometown

Springsteen’s Born In The USA (No.9 US, 1984; No.3 UK, 1985) illustrated listeners’ ability to hear what they wanted to hear, particularly when lyrics are embedded in loud, dramatic instrumentation. Ronald Reagan read the record as a patriotic hymn when it was anything but. An oil worker, ‘Send me off to a foreign land/To go and kill the yellow man’ returns home to find no work, no prospects, no future:

Down in the shadow of the penitentiary

Out by the gas fires of the refinery

I’m ten years burning down the road

Nowhere to run, ain’t got nowhere to go

The chorus, which it seems is all that Reagan registered, after repeated ‘Born in the USA’s’, ends ironically with: ‘I’m a real cool Daddy in the USA’, a characterisation which might also be seen as suggestive of the distance between multi-millionaire entertainers and the people they wrote about.

The 1980s saw a spate of songs composed in solidarity with the struggle against the apartheid regime in South Africa, notably Biko by Peter Gabriel (No.21 UK, 1980, No.33 UK, 1988), Free Nelson Mandela (No.9 UK, 1984) by The Specials AKA; and Eddy Grant’s Gimme Hope Jo’Anna (No.6 UK, 1988). Opposing apartheid was a popular cause compared with other liberation struggles but what attracted entertainers in droves was the far from left-wing Live Aid and its off shoots, and We Are The World. The emergence of British reggae threw up some radical work, the best of which came from Linton Kwesi Johnson on albums like Makin’ History. Steel Pulse’s Ku Klux Klan (No.41 UK, 1978) employed that organisation as a symbol of the rise of racism and the National Front in Britain. Prodigal Son (No.24 UK, 1978) saw Rastafarianism as the answer. Aswad identified with the fight against racism and UB40 – the group’s name was taken from the Unemployment Benefit Form – were in the forefront of the opposition to the impact of Thatcherism. One In Ten (No.8 UK, 1981) lamented the state’s dehumanisation of people by considering them as simply statistics.

Nobody knows me, but I’m always there

A statistic a reminder of a world that doesn’t care

If It Happens Again (No.9 UK, 1984) warned of the consequences of a third Conservative term in office after the 1983 general election. But there was nothing comparable to Bob Marley, particularly his tour de force, Redemption Song.

The Great Miners’ strike of 1984–1985 energised the small minority of radical singer-songwriters. Weller’s new band The Style Council, which had already enjoyed success with Money-Go-Round (No.11 UK, 1983) released Walls Come Tumbling Down (No.5 UK, 1985):

You don’t have to take this crap

You don’t have to sit back and relax

You can actually try changing it

I know we were always taught to rely

Upon those in authority

But you never know until you try

How things just might be

If we came together so strongly …

Are you gonna realise

The class war’s real and not mythologised

And like Jericho – You see walls can come tumbling down!

In songs like Soul Deep (No.20 UK, 1985) by The Council Collective, an extension of The Style Council, Weller and his lyrics were explicit and hard hitting in their support for the embattled miners:

There’s people fighting for their communities

Don’t say this struggle – does not involve you|

If you’re from the working class this is your struggle too

And clear-eyed and candid about the short-sightedness of other trade unionists:

Where is the backing from the TUC?

If we aren’t united, there can only be defeat

Billy Bragg was equally vocal in his solidarity and like Weller put his money where his mouth was. His most successful song, Between The Wars (No. 13 UK, 1985) drew parallels between the 1930s and the 1980s. It was basically an appeal for decency from those in power:

I paid the union and as times got harder

I looked to the government to help the working man

…

Call up the craftsmen

Bring me the draughtsmen

Build me a path from cradle to the grave

And I’ll give my consent

To any government

That doesn’t deny a man a living wage

A Labour Party supporter influenced by punk and folk music, Bragg’s song yearned for a return to a benevolent Britain and what he saw as ‘Sweet moderation, heart of this nation, Desert us not, we are between the wars’. He took a leading part in Red Wedge, a group of musicians established to mobilise the youth vote for Neil Kinnock in the 1987 general election. The Redskins were very different. Members and supporters of the SWP, in a mixture of punk and soul they urged workers to rely on their own power and criticised Kinnock for his role in the miners’ strike. They had a couple of small hits: Kick Over The Statues (No.38 UK, 1985) and The Power Is Yours (No.33 UK, 1986).[18]

The post-punk band, The Men They Couldn’t Hang, explicitly referenced labour history in a series of singles in the later 1980s, such as the Rebecca riots of 1839–1845 in West Wales in Ironmasters, the 1930s anti-fascist struggles in Ghosts of Cable Street (No.94 UK, 1987) and the 1797 naval mutinies at Spithead and the Nore – ‘events of worldwide significance’ in the judgement of Edward Thompson[19] – in the rousing republican anthem Colours:

I was woken from my misery by the words of Thomas Paine

On my barren soil they fell like the sweetest drops of rain

Red is the colour of the new republic

Blue is the colour of the sea

White is the colour of my innocence

The latter was a minor hit (No.61 UK, 1988), despite being banned by the BBC on the grounds that the narrator, ‘a citizen mutineer’, was about to face the scaffold.

Folk Music, the Music of Labour?

Our abbreviated survey of popular song from the 1920s to the 1980s suggests that despite making a greater impression from the mid-1960s, ‘songs of social significance’ rarely figured in the charts. Songs dealing with labour and its problems were rarer still. From the publication of the first Top Ten in the NME on 15 November 1952 when Here In My Heart by Al Martino – who later starred as Johnny Fontaine in The Godfather – was top of the pops, the thousands of songs which made the hit parade have been overwhelmingly concerned with affairs of the heart. The same applies to America. The dislocation between music and labour in the workplace documented by Marek Korczynski and his colleagues has been carried over outside work, at least as reflected by the public’s taste in popular songs.[20] Examining the corpus of music which made the charts may add to our knowledge of some aspects of social history. Those invested in labour and its predicament will encounter comparatively little that is relevant and less that is evocative, insightful, inspiring and aesthetically satisfying.

We are more likely to find songs which reflect these qualities in the field of folksong. It was marked in the post-war years by ‘the second folksong revival’ which gathered momentum and became an established part of the music scene of the 1960s and 1970s.[21] Many, although not all, of its early protagonists were influenced by Communist politics. They aimed at re-animating older traditions, often neglected, of songs produced by workers themselves which expressed their common experience as well as creating new work in a similar style. Approaches varied and developed and many of the initial emphases, American cultural colonisation, rock ‘n’ roll, Tin Pan Alley and commercialisation were the enemy, and songs were best sung without accompaniment, gradually softened and faded away.[22] To provide a sense of the scope and concerns of the British folksong scene in its heyday, I will discuss a small number of songs from England, Ireland and the USA which were popular in the 1960s and 1970s, the highpoint of the revival. They are, it should be stressed, far from representative of the hundreds of songs sung and recorded during these years but express only personal predilections and represent songs I enjoyed and appreciated at the time. They relate not only to the world of work but to the political issues which affected the working class in the past and in the sixties and seventies.

Leon Rosselson, The World Turned Upside Down

Written by Leon Rosselson

Approaching the age of 90 years, Leon Rosselson, singer/songwriter, author of children’s books and political campaigner, is still fighting injustice and oppression and writing songs about it as he has for the last 70 years. From a Communist family – he sang about his background in My Father’s Jewish World – he never seems to have joined the party but supported leftwing causes from the protests against Britain’s invasion of Suez in 1956 and CND from the Aldermaston March of 1958 to opposing the war in Iraq and the policies of the Blair and Brown governments and their Conservative successors. He is a staunch supporter of justice for the Palestinian people who believes folk music may reinforce consciousness but rarely change it. Rosselson first attracted attention when writing songs for the path-breaking, early 1960s television show ‘That Was The Week That Was’ before becoming a fixture of the folk song scene. His songs have typically been topical and satirical, sometime gentle, sometimes fierce, invariably perceptive. Drawing on the traditions of English folk music, European political song and French chanson, they are unusual in the way they sometimes empathise with their targets. On Her Silver Jubilee is a good example: it takes issue with the institution of monarchy rather than Elizabeth II, a woman who, he notes with sad sarcasm, had little choice given her birth and conditioning but to forego a fully human if imperfect life for an existence of privileged dehumanisation:

She doesn’t ride the rush hour, queue for buses in the Strand

She’ll never play maracas in the Ivy Benson Band

Labour historians are greatly indebted for our knowledge of John Lilburne and Gerrard Winstanley, the Levellers and the smaller, more extreme group, the Diggers who espoused a form of primitive communism and their role in the events of the 1640s, to Christopher Hill and a body of work which began with The English Revolution in 1940.[23] My own interest stemmed from reading Comrade Jacob (1961) by David Caute, a novel whose provenance the author traced to Hill’s teaching at Oxford. It was dramatized for television in the early 1960s and the publication of Hill’s classic history, The World Turned Upside Down in 1972 and Kevin Brownlow’s 1975 film Winstanley based on Caute’s book, helped popularise the subject. It was taken up in the 1980s by Tony Benn who termed the Diggers ‘the first true socialists’ and chose Rosselson’s song as one of his choices on ‘Desert Island Discs’. There have been regular commemorative events, Digger festivals, plays by Caryl Churchill (1976) and Jonathan Kemp (2010) and recovery of ballads dated to the period, including The Diggers Song, which Rosselson also recorded. The Diggers have inspired hippies, squatters and Green groups.

The World Turned Upside Down is about the dissolution of the Diggers’ community at St George’s Hall, Surrey, in 1649 and has been recorded by a variety of artists including Dick Gaughan and Billy Bragg. In this rendition, Rosselson’s lyrics – the body of the song is based on a pamphlet attributed to Winstanley – are highlighted by deliberate and unadorned piano accompaniment whose simulated drumbeats evoke a growing atmosphere of muted menace as events move to their conclusion. The words speak movingly for themselves:

By theft and murder

They took the land

And everywhere the walls spring up at their command

They make the laws

To chain us well

The clergy dazzle us with heaven

Or they damn us into hell

We will not worship the God they serve

The God of greed who feeds the rich

While poor men starve.

The reaction of the rich and powerful, as voiced by Rosselson, was swift and decisive:

From the men of property

The orders came

They sent the hired men and troopers

To wipe out the Diggers’ claim

Tear down their cottages

Destroy their corn

They were dispersed

Only the vision lives on

Introducing a new edition of The English Revolution in 1955, Hill reflected on the hopes of the visionaries of the 1640s with their insistence ‘The earth was made a common treasury for all to share/ All things in common, all people one …’ and remarked: ‘… today we can at last see our way to realise the dreams of the Levellers and the Diggers in 1649’.[24] If history makes fools of most of us, we can still dream.

Ewan MacColl, Four Pence A Day

Written Traditional/Thomas Raine

Ewan MacColl (Jimmy Miller) was probably the major influence on the folk scene from the 1950s into the 1970s as collector, scholar, philosopher, organiser, above all and most enduringly, as a singer and songwriter. Raised in Salford by Scottish parents, he was a Communist who followed Stalin then Mao Tse Tung and pursued a lifelong passion for forging a revolutionary culture. An animator of the Theatre Workshop in the immediate post-war years, he increasingly devoted himself to the resurrection and recreation of folk song as the authentic voice of the working class and an important means in reconstituting it as a radical force capable of playing its part in transforming society. Engaged with the Workers’ Music Association, Topic Records, the ‘Ballads and Blues’ and the Singers Club as well as grasping any openings the BBC then offered, MacColl was prescriptive and proselytising. He created the Critics Group to educate a new generation of singers in his own philosophy, was intolerant of commercialism and scathing about those who sacrificed their native traditions for the seductions of popular, particularly American, music. Like many, he mellowed with age.[25]

Joan Littlewood recalled that she and MacColl collected Four Pence A Day in 1948 from John Gowland, a lead miner in Teesdale. She remembered that visiting the area, ‘I amused myself collecting fragments of an old song and got Jimmie [MacColl] a job completing it’.[26] The relationship between the fragments and the final version, recuperation and reconstruction remains vague, and Thomas Raine, ‘The Bard of Teesdale’ to whom the song is sometimes attributed, obscure. MacColl dated it to the early 1800s, a time when the Teesdale iron ore mines were owned by the London Lead Company. Its subject is the boys who together with disabled workers were employed to separate and wash the lead-bearing rocks from the clay and detritus so that they could be dressed and crushed to extract the valuable lead. The work regime was harsh and trade unionism weak and localised, although by 1900 the strongest organisation, the Cleveland Union, enrolled 7,500 out of 9,000 miners.[27] The singer – perhaps ironically, perhaps not – muses on the possibility of morality triumphing over economy and the boss undergoing a conversion to justice and even generosity: ‘His conscience it may fail, aye his heart it may give way/Then he’ll raise our wages to nine pence a day’.

We know too little about the lives of these miners and how they viewed justice and exploitation but the song, as it stands, folksong or ‘fakesong’, reflects the ability of workers to depict and protest their conditions in a way that is still instructive and enjoyable today.

It’s early in the morning, we start at five o’clock

And the little slaves come to the door to knock, knock, knock

Come my little washer lads, come let’s away

It’s very hard to work for four pence a day

… My daddy was a miner and lived down in the town

T’was hard work and poverty that always kept him down

He aimed for me to go to school but brass he couldn’t pay

So I had to go to the washing rakes for four pence a day

Four Pence A Day was recorded by MacColl on a Topic EP in the 1950s but enjoyed increased popularity when reissued on his LP, Steam Whistle Ballads, in 1964.In the best tradition of folksong, it was soon parodied in Stan Kelly and Eric Winter’s Four Pounds A Day, recorded by the Ian Campbell Folk Group:

Four pounds a day, my lads, and nothing much to do

No trouble from the foreman, he’s in the union too

Some want the rain to go to Spain, we want the rain to stay

We’re rained off and contented on four pounds a day

If the sentiments may not have been out of place in the Mail or the Telegraph of the time, Kelly, a computer programmer from Liverpool and Winter, editor of Sing magazine, were staunch if irreverent socialists. I don’t know how MacColl felt about it. But we took the song as a celebration of workers taking back a fraction of the surplus value the bosses had appropriated from super-exploitation in the construction industry.

Luke Kelly and The Dubliners, Dirty Old Town

Written by Ewan MacColl

This is probably the best known of MacColl’s songs, with the exception of The First Time Ever I saw Your Face, a song surely overdue for the Spike Jones treatment. Dirty Old Town was written in 1951 for the play, Landscapes with Chimneys, a drama about homelessness, the slums and the 1946 Squatters’ Movement. MacColl recorded it for Topic and in 1959 it became, so far as I know, the first of his songs to be aimed – unsuccessfully – at the pop charts, in the shape of a Decca single by Mike Preston, who achieved a measure of fame with his cover of The Fleetwoods’ Mr Blue. Dirty Old Town was subsequently recorded by The Clancy Brothers, The Dubliners, Donovan, The Spinners and Rod Stewart among numerous others. It became a folksong. It was 1985 before The Pogues took it into the Top 40 where it reached No.34. The song is based on MacColl’s early experience. His Salford, which he shared with Walter Greenwood and Love on the Dole, like Harold Brighouse’s Edwardian Salford of Hobson’s Choice or Shelagh Delaney’s later Salford of A Taste of Honey, no longer exists. For better or worse, the city has undergone sweeping physical change, particularly in recent decades. And if some of its citizens felt the popularity of the song brought little credit to the area, others proved willing to apply its sentiments to their own ‘dirty old towns’. In 2003, Simple Minds released a charity single on the ‘Bhoys from Paradise’ label, featuring Jimmy Johnstone, Celtic’s most beloved ball playing genius since Charlie Tully. In 2008, The Spinners’ version appeared on the soundtrack of Terence Davies’ elegy to post-war Liverpool, Of Time and the City.

The melody permits a contagious, loping, ride-along arrangement, emphasised in the version by the country singer, George Hamilton IV. The lyrics evoke the urban grime of the post-war years, the soot-stained buildings, the docks, railways, gasworks, factories, canals and Victorian housing of Britain’s gloomy monuments to the first industrial capitalism, battered and scarred by Hitler’s bombers. They configure and confine but can never extinguish the vibrancy of life. Workers still find love and beauty in the dirt and dreariness: ‘I met my love by the gasworks croft/ Dreamed a dream by the old canal … Smelled the spring on the smoky wind …’.[28] Nonetheless, the song demands more than slum clearance, affordable housing, fewer chimneys and more smoke control. It concludes with support for revolutionary transformation facilitated by disciplined organisation and action:

I’m going to make a good sharp axe

Shining steel tempered in the fire

We’ll chop you down like an old dead tree

Dirty Old Town, Dirty Old Town[29]

Brendan Behan, The Captains And The Kings

Written by Brendan Behan

Brendan Behan’s song, to the tune of the old air, Roses In Bloom, was written for his play The Hostage. First performed by Joan Littlewood’s Theatre Workshop at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East in 1958, its success saw Behan approach the height of his brief celebrity. He came from a passionate Republican and musical Dublin family. His uncle, Peadar Kearney, wrote the words to Amhran na bhFiann, The Soldier’s Song, the national anthem of the 26 counties. He joined the IRA at 16. Still a teenager, he served several spells in prison and Borstal in England, having participated in the abortive 1939 bombing campaign and was subsequently interned by the De Valera government at the Curragh Camp. The Hostage presented a complex and contradictory take on Anglo-Irish relations. The play lampooned both imperialism and nationalism and suggested the distance between romance and myth and the prosaic, sometimes squalid, reality of politics. The story centred on the kidnap of an English soldier in retaliation for the impending execution of an IRA volunteer. The Captain And The Kings is sung in the play by Monsewer, an unhinged Anglo-Irish convert to republicanism and a veteran of 1916.

Removed from its conflicted context, the song functions as a caustic caricature of English imperialism and its entitled protagonists. Decca released a single by Dominic Behan in 1959 and Brendan included it on his LP, Brendan Behan Sings Songs From The Hostage and Irish Ballads the following year. Over the next decade, it found its way into the repertory of Irish balladeers and many considered Ronnie Drew’s version with The Dubliners as definitive. Elvis Costello produced a single by the Dublin singer Philip Chevron and performed the song himself in the 1980s. Delivered in the portentous drawl and affected BBC accent commonly adopted by their Irish – and English – critics to mimic and mock those who consider themselves out of the top drawer, the song satirises the bourgeoisie’s enduring colonial mentality in the twilight of empire:

I remember in September when the final stumps were drawn

And the shouts of crowds now silent and the boys to tea have gone

… We have many goods for export, Christian ethics and old port

But our greatest boast is that the Anglo-Saxon is a sport

The lyrical offensive continues intoned with faux solemnity:

In our dreams we see Old Harrow and we hear the crow’s loud caw

At the flower show our big marrow takes the prize from Evelyn Waugh

If the sun is setting, imperialism lingers on abroad and nearer home:

Faraway in dear old Cyprus or in Kenya’s dusty land

Where we who bear the white man’s burden in many a strange land

As we look across our shoulder in West Belfast the school bell rings

And we sigh for dear old England and the Captains and the Kings

The references to ‘the white man’s burden’, ‘Christian ethics’ and so forth indicate the Kiplingesque subtext generally and relate more specifically to the poem, Recessional – the title of the song is taken from Kipling’s lines:

The tumult and the shooting dies

The Captains and the Kings depart

Written for Queen Victoria’s Silver Jubilee in 1897, it is a cautionary tale in which Kipling observes the transience of world domination. England’s imperial mission had only been possible with divine approval and its continuance was contingent on God’s blessing and the maintenance of Christian morality. Behan was a life-long critic of the hypocrisy he saw as inherent in utilising religion to justify racism and pillage. He was scathing about ‘the Christian ethics’ of the Establishment, particularly the Church of England and its adherents, and frequently quoted sentiments he attributed to a 16th century Gaelic preacher:

Don’t speak of the alien minister

Nor his church without meaning nor faith

For the foundation stone of his temple

Is the bollocks of Henry the Eighth[30]

The Captains And The Kings concludes:

By the moon that shines above us in the misty morn and night

Let us cease to run ourselves down and praise God that we are white

And better still are English, tea and toast and muffin rings

Old ladies with stern faces and the Captains and the Kings

Old ladies with stern faces and the Captains and the Kings

Imperialism has changed its form – witness the British state’s recent enthusiasm for anti-racism and multi-culturalism. It is still with us, shaped by the UK’s subordination to the US hegemon, not least in the labour movement, a judgement aptly affirmed by the career of Tony Blair and the fate of Jeremy Corbyn.

Leon Rosselson, Palaces Of Gold

Written by Leon Rosselson

In autumn 1966 a slag heap collapsed at Aberfan, South Wales. The rubble enveloped the pit village, buried a school and killed 116 children and 28 adults. For Rosselson, the incident confirmed his conviction that ordinary people can never trust those in authority and set him thinking about Britain’s under-resourced, unequal and segregated education system which operated to determine life chances and destinations, and, for the most part, allocated children to their parents’ class. The offspring of the elite were educated in the misnamed ‘public schools’, private institutions subsidised from the public purse; children whose parents could not afford the fees were consigned to the state system, which in 1966 attracted 46 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at a time when 56 per cent of GDP went on arms and defence expenditure.[31] By and large, public schools received superior resources, enjoyed better facilities, higher spending per pupil, lower staff-pupil ratios and better examination results.

Rosselson’s song is an imaginative exercise in ‘What if?’ It ponders that transformation of state education if a Labour government ever had the audacity and courage to abolish the public schools, presenting the richer elements of society with their money, social skills and political pull with little alternative but to use the state sector:

If the sons of company directors

And judges’ private daughters

Had to go to school in a slum school

Had to herd into classrooms cramped with worry

With a view onto slagheaps

Had to file through corridors grey with age

And play in a crackpot concrete cage

Unlike Labour, the privileged would act decisively. The few would not accept what they had insisted was more than sufficient for the many. They would pursue their own interests as they always did. Power would be mobilised:

Buttons would be pushed

Strings would be pulled

And magic words spoken

Invisible fingers would mould

Palaces of Gold

Over half a century later, the ‘human rights’ and ‘civil liberties’ of company directors and judges, their freedom to spend their hard-earned cash to purchase and perpetuate privilege, ensure their offspring become company directors and judges and insulate them in their formative years from engagement with working-class children in classrooms ‘cramped with worry’ and ‘corridors grey with age’, still flourish. In the context of the historic underinvestment in British education which accelerated from 2010, Labour leader, Keir Starmer, declines to promise any radical reversal and retreats on earlier commitments to strip public schools of their charitable status or the means by which the many continue to subsidise the few. In 2023, the National Audit Office reported, ‘Following years of underinvestment, the estate’s overall condition is declining and around 700,000 pupils are learning in schools that the responsible body of DfE believes need major rebuilding’.[32] In the wake of the RAAC concrete crisis, the Minister of Education claims pupils prefer being taught in Portakabins rather than crumbling classrooms. Palaces of Gold.

Paul Brady, Arthur McBride And The Sergeant

Written by: Traditional

Ireland is notable for fine and enduring songs depicting the human costs of war such as the ubiquitous and macabrely humorous Johnny I Hardly Knew Ye – known in America as When Johhny Comes Marching Home – Mrs McGrath and The Kerry Recruit. Mrs McGrath was most recently popularised by Bruce Springsteen on his 2006 album, We Shall Overcome. It enacts tragedy with comedic con brio:

Oh! Mrs McGrath the Sergeant said

Would you like [to make] a soldier of your son Ted?

With a scarlet coat and a big cocked hat

Oh! Mrs McGrath wouldn’t you like that?

Seven years or more pass. And then:

Up comes Ted without any legs

And in their place two wooden pegs

Its dating to the War of the Spanish Succession in the early 1700s seems unlikely, given the restrictions on recruiting Catholics which lasted for most of the century and the version we have comes more plausibly from the Peninsular War of 1807–1814. The Kerry Recruit is a song of the Crimean War period. Unlike Mrs McGrath – ‘For I’d rather my Ted as he used to be/ Than the King of France and his whole Navee’ – the Kerry labourer, once ‘a fine, dashing lad tossin’ turf round Tralee’, who has lost an eye and a leg seems, reconciled to his lot and the price he has paid for economic security: ‘Contented with Sheelagh, I live on half pay’.

For a century from the early 1800s, Ireland, given the increasing poverty of its inhabitants, was a fertile source of recruitment for the British forces. A family of songs highlighting the distance between the opportunities for glory and a better life broadcast by the authorities and the grim reality, clustered around the Recruiting Sergeant – like the Press Gang and the Crimping House in sailors’ songs, he was a familiar feature of working-class life across the British isles. ‘The treacle tongued, bloody-minded humbug and bamboozler that men of his agency had to be if they were to induce recruits into the ranks,’[33] was often an object of ridicule and resistance as he exploited naivety, gullibility and the host of economic and personal troubles that afflicted his potential victims. With military service seen as an alternative to migration or poverty. the Sergeants encountered a fair measure of success. However, judging at least by the songs that have come down to us, antagonism, always present, sharpened in the twentieth century as the forces that would coalesce around 1916 crystallised to stem the 1914 tide of volunteering and oppose the introduction of conscription. Acclamation greeted the decline of William Bailey and his ilk:

Some Irish lads with placards have called his army blackguards

And told the Irish boyhood what to do

He’s lost his occupation, let’s sing in jubilation

For Sergeant William Bailey tooraloo

In song at least, insult and derision were common:

When I was young I used to be as fine a man as ever you’d see

The Prince of Wales he said to me, come join the British Army

Tooral ooral ooral oo, they’re looking for monkeys in the zoo

And if I had a face like you I’d join the British Army.

Arthur McBride is an older song, found all over the British Isles and beyond. A. L. Lloyd described it as ‘that most good-natured, mettlesome and unpacifistic of anti-militarist songs’.[34] It became a favourite with folksingers and notable versions were recorded by Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick in 1969, by Planxty in 1972, and by Bob Dylan twenty years later. Brady, who had been a member of Planxty, recorded what is often regarded as the definitive version adapted from a songbook by Carrie Grover of Maine, for the much admired Andy Irvine-Paul Brady album in 1975. On what became known in Ireland as ‘the purple album’, it is preceded by the old Ulster song, Bonny Woodhall, a moving reminder of what fate held in store for those enticed by recruiters’ glowing prospectus of army life in which a young miner dreaming of a better future enlists to provide for his prospective bride only to return maimed in body and broken in spirit.

In Arthur McBride, potential recruits turn the tables and the sergeant comes off worst. The song’s hypnotically rising and falling melody is carried along by intricate guitar work which never obscures lyrics strong in imagery as Brady’s sinuous voice recounts a dramatic Christmas Day story. A chance meeting on the seashore on ‘a pleasant and charming’ Christmas morning between Arthur and his cousin and two recruiting officers and ‘a wee little drummer’ moves from courteous exchange to disagreement and violence after Arthur exposes the speciousness of the sergeant’s sales pitch, his awareness of the harsh discipline and restrictions of army life – for which the 10 guineas in gold enticement is poor recompense – and the hazards it holds for the unwary:

You would have no scruples to send us to France

Where we would get shot without warning

The shills are outwitted and outmuscled by their intended marks. The violence of the oppressed is vindicated as rusty rapiers prove no match for shillelaghs:

We lathered them there like a pair of wet sacks

And left them for dead in the morning

Ewan MacColl, The Shoals Of Herring

Written by Ewan MacColl

Shoals Of Herring was written for ‘Singing the Fishing’ – the third of the BBC series of Radio Ballads produced between 1958 and 1964 – which was broadcast on the Home Service and Third Programme in 1964 and won the prestigious Prix Italia. The project was developed by the BBC producer, Charles Parker, MacColl and Peggy Seeger, with each documentary based on the sounds of industry, the voices of its workers and songs by MacColl, which expressed their experience, attitudes and pre-occupations in an attempt to portray the life of the working class. In the case of the fishing industry, which had not been greatly explored in the literature, labour historians are indebted to Paul Thompson and his colleagues who in the early 1980s published a detailed study based on extensive interviews with fishermen about their work and their communities.[35] It takes us beyond ‘Singing the Fishing’ and provides essential context for it.[36]

MacColl’s song drew on the life of Sam Larner, an 82-year old Norfolk fisherman, remembered in his own words taken down and played back by MacColl with the resulting lyrics sung to a variation of the old tune, The Famous Flower Of Serving Men. Larner had as a youth sailed on a lugger but spent most of his working life on steam trawlers. He was not a typical fisherman: he started work in Victorian England and was well known as a carrier and performer of traditional songs who became part of the folksong revival. The song narrates his initiation into work and his rites of passage into the fraternity.

Oh the work was hard and the hours were long

And the treatment sure it took some bearing

There was little kindness and the kicks were many

As we headed for the shoals of herring

Working his way from cabin boy to cook to skilled worker, he is accepted into the craft and community and becomes a man:

Now you’re up on deck, you’re a fisherman

You can swear and shout and show a manly bearing

and exudes pride in his hard-earned new standing:

Oh I earned my keep and I paid my way

And I earned the gear that I was wearing

MacColl created a beautiful song which for many evoked the romance of the sea and sailing rather than the tribulations of the daily grind of the trawlermen. It is faithful to the recollected general satisfaction and fulfilment Larner found in his work. Any sense of alienation is absent, together with MacColl’s Marxist vision if we discount the nod to hard knocks for apprentices. Many workers in the 1960s, including trawlermen, looked back on a lifetime of labour and told a less benign story.[37] Whatever its general application, MacColl fashioned a folksong. When I first heard it, sung by the Corries around 1963, I thought, like not a few other listeners I later discovered, I was listening to a traditional song called The Shores Of Erin, Shoals was immensely popular in folk clubs and beyond, particularly in Ireland. It was recorded by The Ian Campbell Folk Group, The Clancy Brothers, The Dubliners, Lou Killen, The Spinners and numerous others. It remains popular and was more recently recorded by Seth Lakeman. Its iconic status was recognised when it was sung by Oscar Isaac and the Punch Brothers in the Coen brothers’ 2016 film, Inside Llewyn Davis, set in the New York folk scene of 1961.

Leon Rosselson, Tim McGuire

Written by Leon Rosselson