By the spring of 1949, the post-war Labour government had already delivered great swathes of the manifesto on which it had been elected less that four years earlier. The Bank of England had been in public ownership since 1946; the railways, coal industry and road freight had all been nationalized; and the National Health Service was up and running. All of which raised the question of what would come next.

With the promised Bill to nationalize the steel industry set to become law before the end of the year, the party needed a programme to put before the electorate at the rapidly approaching 1950 general election. But when the February meeting of the NEC broke up having spent much of its time debating the fate of the left-wing MP Konni Zilliacus, then facing expulsion from the party, rather than matters of policy, it became clear that the election programme would need to be thrashed out in some other forum. And before the week was out, newspapers were reporting on plans for a ‘highly secret meeting’ to be held that coming weekend (Manchester Evening News, 24 February, p.1).

That day, a Friday, news broke that members of Labour’s National Executive Committee (NEC) had been ‘summoned to an urgent conference at Shanklin, in the Isle of Wight, this weekend’ (Daily Mirror, p.1). The prime minister, Clement Attlee, would attend, but no Minister who was not also an NEC member had been invited, the paper reported. ‘The reason for the meeting is the difficulties which have arisen over the framing of the Party policy for the next general election.’ There was, it said, still a gap between the views of the unions and those of the politicians on the NEC – with a battle expected over the unions’ demand for nationalization of the shipbuilding industry.

It had been hoped to keep the conference a secret, reported the Mirror, which along with much of Fleet Street and the provincial daily press, duly splashed the story on its front page. If secrecy had been the plan, then it had failed miserably. As other papers got hold of the story, so more details of the summit emerged. Soon it became clear that every member of the Cabinet, and a small number of Ministers outside it, had also been invited.

In the absence of much information about the course of policy debate, the papers were full of the detailed minutiae of the weekend. The Daily News and other papers, most relying on syndicated agency copy, reported that the event was to be held at a guest house owned by the Workers’ Travel Association in the town of Shanklin (25 February, p.1). The Huddersfield Daily Examiner and others (25 February) noted that only four women were to take part: Dr Edith Summerskill, MP for West Fulham; Alice Bacon, MP for North East Leeds; Margaret Herbison, MP for North Lanark; and NEC member Eireen White. ‘Some other women will be at the guest house where the conference is to be held, but they are party officers or secretaries attending in their official capacity.’

The papers were united in their expectation that all those attending would travel on that Friday evening by train from London Waterloo to Portsmouth, and then ‘in the ordinary steamer’ to Ryde, from where they would be ferried in a fleet of cars to Shanklin. Reporting for the Yorkshire Evening Post, William Sternberg wrote that ‘special police protection’ was being laid on for the ‘hush-hush conference’, and that his own attempts to book a room at the guesthouse, which he noted did not have an alcohol licence, had been rebuffed.

The following morning, regional and local papers including the Birmingham Daily Gazette (26 February, p.1) carried news of the politicians’ arrival on the Isle of Wight. They reported that Bevin had been the only well-known figure spotted on deck as the new British Rail ferry Brading arrived at Ryde pier. First off, however, had been Morrison, followed a few seconds later by Hugh Gaitskell. They were greeted by a hostile crowd between 150 and 200 strong who shouted ‘snoek’, ‘give us more fats’ and ‘what about the coal?’

But when they arrived at the gates of the guest house, a small group of ‘little girls’ were more enthusiastic. In best Enid Blyton style, the Birmingham Daily Gazette recounted the scene: ‘“Hurray,” shouted Ann (14), Josephine (13) and Gillian (11), and a spaniel joined in the demonstration by barking. “We are all strong Labour supporters,” said Ann.’

More substantially, lobby correspondents told their readers that there would be no votes, and no decisions at the conference. ‘Mr Attlee is here with practically all his Cabinet, but it is strange though true that as a body they count for less in this policy-producing conference than the 28 members of the executive, half of whom are not even MPs.’ (Liverpool Echo, 26 February, p.3). Rather, decisions would rest with the NEC alone at a later meeting, because when the election was called, the Cabinet would be dissolved while the NEC would lead the party into battle.

Explainers such as this aside, the papers had nothing to tell their readers about the discussions that went on at Shanklin. The level of interest, however, was intense, with what would appear to have been a small army of photographers capturing every step of the journey and every slight rattle of the iron gates which kept them at long-lens length from the politicians.

The Daily Herald (28 February, p.2) reported that party leaders had enjoyed ‘a most relaxed dinner’ on the Saturday night, presided over by Herbert Morrison, who as Lord President of the Council chaired the Government’s committee on the ‘socialization of industry’. Morrison, the paper reported, sang a verse of Omar Kayyam ‘in a surprisingly rich baritone voice’, before Aneurin Bevan ‘obliged with a ballad’. George Tomlinson, the Education Minister, told some amusing Lancashire anecdotes, with Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin joining in with some funny stories of his own.

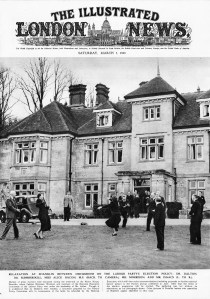

The politicians were clearly still in light-hearted mood on the Sunday morning, allowing in photographers from the less news-led publications to snap them in the grounds of the guesthouse. Both The Sphere and the Illustrated London News (5 March 1949) filled their front pages with a single image of the party leaders at play, and each carried a further full page of smaller photographs inside.

Even after the conference had come to an end, details of the policy programme that had been hammered out remained vague. The Daily News (28 February, p.1) was typical in headlining its front page ‘Labour clears decks for 1950’ and reporting that the party had decided to go to the country with ‘a second Five-Year Plan of moderate Socialist expansion, consolidation and development of industries already nationalised’ along with a ‘radical reorganisation’ of the distributive trades to cut the cost of living.

In due course, some of the conference’s conclusions would reach the Labour Party conference in Blackpool in June, though Clement Attlee in his leader’s speech would focus far more on what his government had achieved in its first term than on what it hoped to do in its second1. Much of the party’s plans for the second term would remain under wraps until February 1950, when it published its election manifesto Let Us Win Through Together2, and it became clear that Morrison, who was cautious about further nationalization, had won out over the trade unions, with the promise of no more than a ‘development council’ for the shipbuilding industry.

1. Clement Attlee’s speech to the 1949 Labour Party Conference on the British Political Speech website.

2. Labour Party election Manifesto, 1950.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.