Dr Quentin Gasteuil explains how he tracked down Elinor Bethell, a little known British woman who played a leading role in the Labour Party in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s, with help from an SSLH bursary.

I came across the widely unknown character of Elinor Frances Bethell during my PhD research. When I first made archival contact with her, she was a British woman living in Paris in the 1920s. She hosted meetings between French Socialists and leaders of the Labour Party when they came to France. Additionally, she was involved in managing the Paris group of the British Labour Party with other British exiles.

After completing my PhD, I decided to further investigate Elinor’s biographical details. Who precisely was this wealthy left-wing woman? What brought her to Paris? I discovered that she came from an aristocratic background, that she was a former Conservative. She had been a widow twice and relocated to Paris after the death of her second husband, where she lived on her own with her domestic servants. Her trajectory was intriguing: how did she manage to navigate these different aspects? Eventually, my purpose became to understand how her profile and her originality allowed to address various social, gendered, political and transnational historical dimensions.

Despite the considerable amount of information available online, I decided to cross the Channel for further inquiry. The grant I generously received from the Society for the Study of Labour History enabled me to order documentation such as birth and wedding certificates. Nevertheless, above all, it was an opportunity for me to embark on a sensitive archival journey, searching for Elinor. I travelled to England for 10 days in February and March 2023.

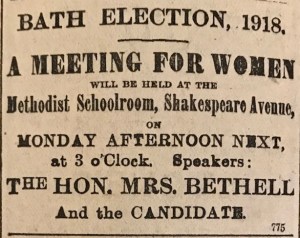

At the British Library, I worked on Elinor’s personal papers dedicated to her research on the French Socialist Louis Blanc (1811-1882). Through her correspondence and her documentation, I was able to have insights into her personality, political beliefs, and even aspects of her daily life. I examined Bath newspapers from 1918 to identify Elinor’s involvement in her second husband’s electoral campaign. He was running for the general election under the Labour colours, which were new to both him and his wife. Additionally, I attempted to track her frequent changes of residence through local directories. In another part of London, Elinor’s granddaughter, who is 100 years old, shared stories about the woman she had known when she was a girl. She also provided insights into Elinor’s everyday life in Paris in the 1920s and in Britain in the 1930s.

I then travelled North, to Yorkshire, as I was expected in Boroughbridge by Elinor’s great-grandson. I visited Aldborough Manor, where she had lived with her first husband – and where she spent her last months. There, a few archival papers were available to consultation, especially family photographs and press cuttings regarding the first part of her life. They helped me to capture a more vivid picture of Elinor. It was also moving to visit the family section in the local churchyard where Elinor’s grave is to be found among the family of her first husband.

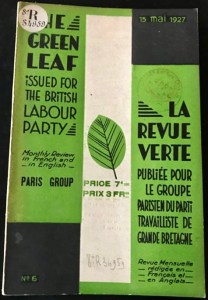

My next destination was Manchester. Since Elinor was involved in running the Parisian branch of the Labour Party and was connected with the Fabian Society, I tried to find evidences of her political activities in the Labour Party archives at the Labour History Archive and Study Centre (LHASC). I examined multiple sources – party press, administrative archives, official and private correspondence. Yet the exploration proved disappointing, as I only found small traces of Elinor’s activity. The connection between the Paris group and the headquarter in London seemed to be very weak, to say the least, and Elinor to be an evanescent character for her fellow party members.

With the help provided by the Society for the Study of Labour History, I was able to outline more precisely the type of woman Elinor was, the life she lived, and the way she dealt with the different aspects of her existence. Many answers can be found in the analysis of the entanglement of some of her characteristics, especially the fact that she was, in the interwar years, a woman and a wealthy widow in her fifth and sixth decades. It paves the way for an analysis that explores the intersection of political and family histories. The role played by the social and political environments she belonged to, as well as her own personality, also seem to be very fruitful in understanding her personal trajectory – and especially the apparent deviations within it.

How could I put Elinor’s story into words? At first, I wanted her life to be the object of a scientific article but the more I discovered, the more I was keen on writing an academic book. However, I also realised that it would be important to show my research process as well. How did I look for Elinor? This is now my aim: a cross-writing between the life of Elinor and my investigations about it. Nevertheless, beyond that writing, I do not exclude other media to share this knowledge: why not a podcast, a graphic novel or a stage performance? Wondering about the medium is also a way of thinking out of the box.

Dr Quentin Gasteuil, Institut des sciences sociales du politique, École normale supérieure Paris-Saclay

Find out more about bursaries available from the Society for the Study of Labour History.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.