Dramatists have been slow to pick up on the events at the heart of the great strike of 1842 and its complex relationship with Chartism. Michael Crowley, the author of Waiting for Wesley, explains how he went about bringing the story to life on stage

Waiting for Wesley is being staged at Calderdale Industrial Museum on Sunday 6 August at 3pm Tickets are available via Eventbrite, here.

I decided to write a play about the great strike of August 1842. I did so because I wanted other people to know about those events. How extraordinary they were. Many people I know, politically committed or otherwise, historically literate I might add, know little or nothing about the seismic upheaval of that year. I knew I would enjoy the research and, hopefully, the writing. Furthermore, I’d never seen a stage play or a film that covered the subject in detail, a drama that had the most significant single exercise of working-class strength in nineteenth-century Britain at its epicentre. Its place on stage or screen is long overdue.

Chartism, the political movement inextricably linked to the strike, is represented in several nineteenth-century novels. Sybil by Benjamin Disraeli was published in 1845. The heroine’s father is a chartist, and the plot unravels during the 1840s. Disraeli was genuinely interested in Chartism, if not sympathetic, and Sybil is arguably one of the most important ‘Condition of England’ novels of the Victorian era. Mary Barton (1848) by Elizabeth Gaskell is set between 1839 and 1842, with the protagonist’s father throwing himself into chartist politics and trade unionism. Gaskell published North and South in 1854, which is also set against an industrial dispute in Manchester in the same era. Both novels have been adapted for the screen. The Chartists themselves had their own literature. Ernest Jones was a prolific poet and novelist. The Newport Rising of 1839 is depicted in a play, John Frost, by John Watkins. The piece didn’t get much further than extracts in The Northern Star and may be worth revisiting.

Rather than Chartism, it is two other landmark events that have been dramatised by contemporary cinema: Mike Leigh’s Peterloo (2018) and Comrades (1986) by Bill Douglas. Leigh’s film reimagines the build-up to the massacre on St Peter’s Fields in Manchester in 1819 when a demonstration demanding suffrage reform was attacked by yeomanry with at least 20 demonstrators killed. Comrades dramatises the case of the Tolpuddle Martyrs, six Dorset agricultural labourers transported to Australia for forming a Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers. Chartism, too, has martyrs from Preston to Newport and Halifax. However, they are perhaps less likely to evoke the same easy pathos as Peterloo and Tolpuddle. Chartism and its relationship to the great strike of 1842 is a complex story and politically more contentious than Peterloo or Tolpuddle. Still, I would argue, because of that, it provides a great deal for dramatists to work with.

Individuals such as Ernest Jones, Feargus O’Connor, and Ben Rushton provide the basis of compelling characters. Jones was born into money but sacrificed his wealth for the cause of Chartism. He advocated physical force to acquire social change and was imprisoned for his speeches. While in prison, it is said he wrote an epic poem in his own blood. O’Connor was an Irish nationalist and founder of the newspaper The Northern Star. A physically impressive figure, he was the movement’s most celebrated orator. Also imprisoned for his speeches, he was oddly ambivalent about the strike of 1842. Rushton was a weaver from West Yorkshire. He was initially a methodist, and his oratory at one time drew heavily from the Bible. He then broke with organised religion and urged people not to attend services which were at odds with civil liberties.

Dramatists often talk about three levels of conflict: the individual versus the world; the individual versus another individual; the individual versus the self, their conscience. 1842 provides ample opportunities. Chartists in opposition to employers and magistrates, or to other chartists opposed to physical force, or the strike itself. Division inside families, between strikers and strikebreakers, a conflict of conscience on any side of the dispute. Indeed, it would be interesting and refreshing to enter the narrative through the perspective of a Hussar. In my play, Waiting for Wesley, I’ve chosen to go through the door of a divided family. A millworker dedicated to the charter and his wife, who has recently found Methodism. (It has occurred to me what possibilities there are in reversing the roles). Behind their differing searches for salvation lies the loss of a child and the persistent surfacing of blame.

Mounting tension and jeopardy are inherent in the narrative of 1842. The strike gained momentum in the Staffordshire coalfield. Its objective, there, was the restoration of recent wage cuts. But as the strike migrated geographically, so it did in terms of demands, with other groups of workers demanding the ten-hour day and, in some instances, the implementation of the People’s Charter. Though its degree is in contention, there were without doubt political aspirations amongst the strikers, and it is the political ambitions of some, a revolutionary minority, that make the subject problematic for writers.

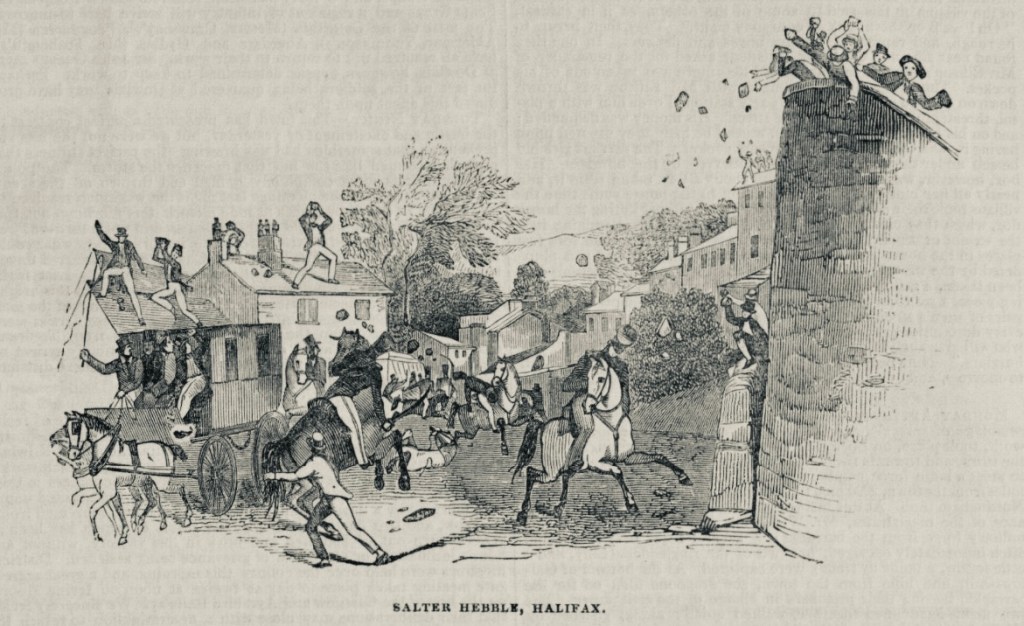

The action during August swept northwards from the potteries into Cheshire, Lancashire, then the West Riding. By 15 August, between 20 and 30,000 strikers were present in Halifax, and the authorities must have felt they had lost the town. Special constables, where they could, seized bludgeons from strikers. When soldiers seized some strikers, others attempted to free them and were met with gunfire and fixed bayonets. As at Peterloo and Tolpuddle, the conflict is resolved by oppression. Yet an audience would know that nothing will be the same, for the cost of suppressing the movement has left behind the bereaved and a political legacy.

I would encourage writers of all forms to explore the events of August 1842. The cast of strikers is not a passive audience for an orator. They are taking matters and history into their own hands. Demanding the vote in 1842 was a revolutionary quest. It would have led to majority rule to working-class power, and the industrial revolution would have had a different, arguably more humane complexion as a result.

Waiting for Wesley is being staged at Calderdale Industrial Museum on Sunday 6 August at 3pm Tickets are available via Eventbrite, here.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.