This year’s Chartism Day was in Sheffield, with papers on the land plan, the poet Thomas Cooper, the ‘paper pantheon’, Chartism’s first historian of the modern era, and the lives of Chartists in France

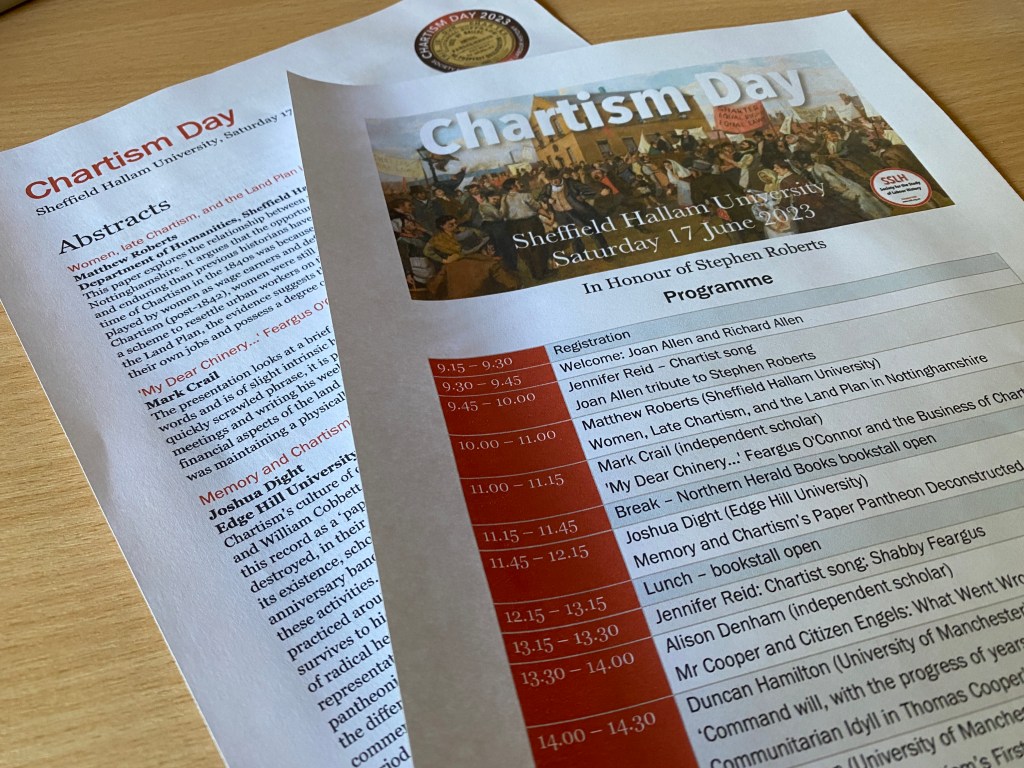

Held on Saturday 17 June, Chartism Day 2023 opened with a fitting tribute to Stephen Roberts – the organiser of the first such event in 1995, and a leading Chartist historian in his own right over many years.

Dr Joan Allen, who had known Stephen since those early days, recalled him as ‘a generous man who gave freely of his time and always found time to share his knowledge with others’. She noted his commitment to preserving and advancing the work of his mentor, Dorothy Thompson; to publishing his own work, notably the groundbreaking book Images of Chartism; and to supporting wider historical research through his work on Chartist bibliographies.

Further reading: Obituary: Stephen Frederick Roberts (1958-2022).

That first conference took place in Birmingham; in 2023 it was hosted at Sheffield Hallam University, and as always was open to both an academic and non-academic audience. This is an event that many attend year after year, while others may come just once to hear a paper of particular interest to them.

Broadside ballad singer Jennifer Reid opened this year’s conference with rousing renditions of Tyrants of England (also known as The Hand Loom Weaver’s Lament) and The Weaver of Wellbrook, two traditional Lancashire radical songs popular in the nineteenth century and of special importance to Chartism.

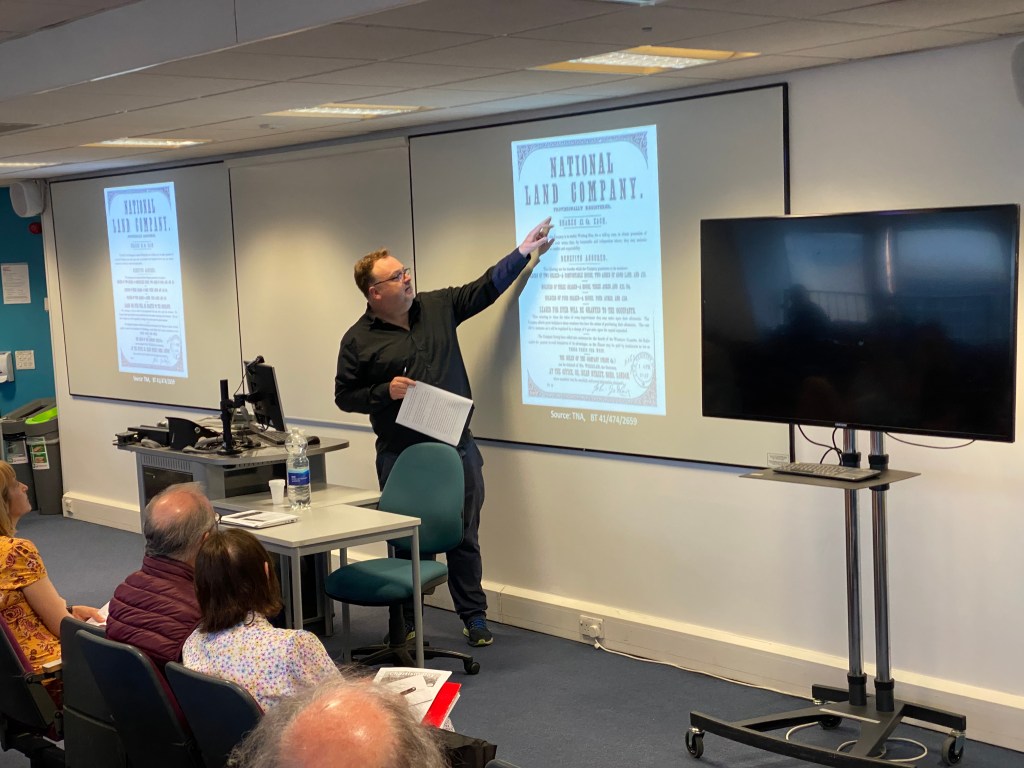

Dr Matthew Roberts (Sheffield Hallam University) drew on the Chartist Land Company share registers (held in the National Archives) to demonstrate that working-class women’s involvement in Chartism in the mid to late 1840s was more varied and more enduring than is often said to be the case.

The land company was established with the aim of resettling industrial workers on the land, with smallholdings of their own, providing independence and the possibility of the vote. It succeeded in establishing five settlements or colonies, with land allocated on the basis of a ballot among the company’s tens of thousands of small shareholders.

Drawing on a database of some 2,300 Nottinghamshire members, Dr Roberts found evidence to suggest that the region’s women were more likely to join, to do so of their own volition, to have their own jobs and to possess a degree of independence than was the case elsewhere.

Further reading: Matthew Roberts (2023) Women, Late Chartism, and the Land Plan in Nottinghamshire, Midland History.

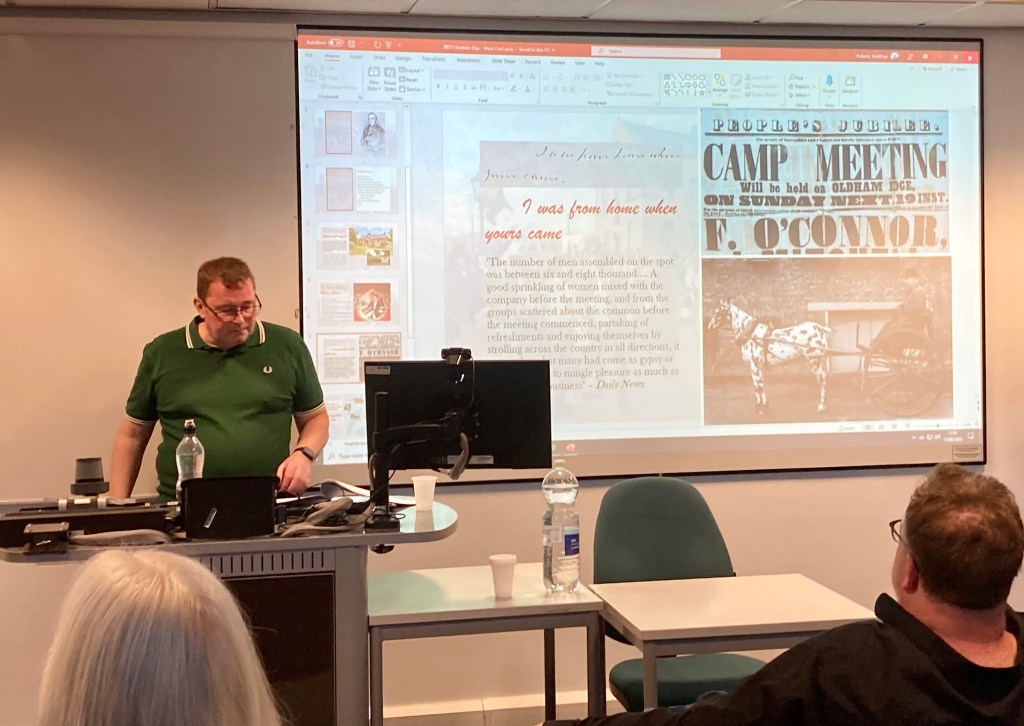

Continuing the land company theme, Mark Crail dissected an 1847 letter written by the Chartist leader Feargus O’Connor from his home at the Snig’s End settlement to George Chinery, his lawyer’s chief clerk, who was charged with much of the legal work involved in purchasing estates for the land company and the ultimately futile attempt to establish a legal basis for its work.

Although only fifty words in length, the letter demonstrated O’Connor’s involvement in the politics of Chartist decision-making, the purchase of land, the setting up of a Chartist bank, and his constant travelling to speak at Chartist events – an important element in his leadership and encouragement of the wider movement.

Joshua Dight (Edge Hill University) brought the morning session to a close with paper that showed how Tory, Whig and Chartist newspapers each created their own ‘paper pantheon’ of heroes around which their readerships could unite – and attacked each other through these individuals.

The eighteenth century radical Thomas Paine was the most significant member of the Chartist pantheon; however, Dight was able to show that though there were common elements to the ways in which Paine and others were commemorated, there were also differences of emphasis in these commemorations and how they were reported.

After the lunch break, Jennifer Reid once again invigorated the audience with her version of the song Shabby Feargus – originally a none-too-respectful poem about the Chartist leader written by the Chadderton weaver Samuel Collins. You can see – and hear – her performance below.

Further reading: A Chartist Life (1): Samuel Collins (1802–1878) Presentation by Janette Martin to Chartism Day 2022.

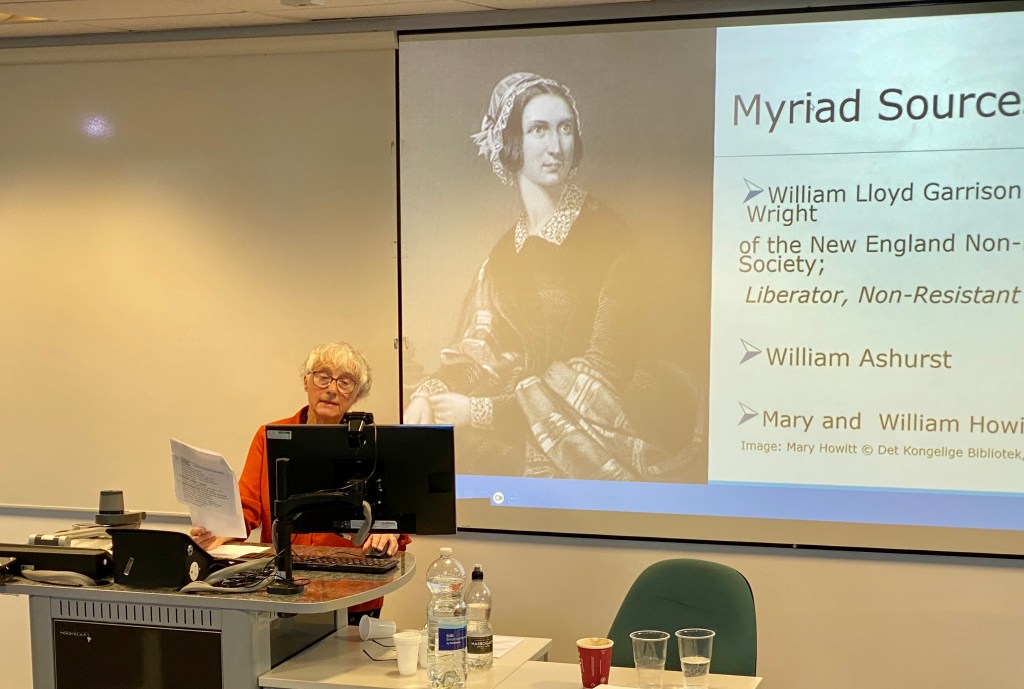

Alison Denham delivered a paper titled ‘Mr Cooper and Citizen Engels: What Went Wrong?’ She noted that in the summer of 1845, the controversial Chartist poet and the German socialist were on good terms – with a shared interest in poetry and political common ground in their support for international causes. Within a matter of months, however, the two men were at loggerheads, and the relationship had broken down.

Denham traced this split to Cooper’s growing friendship with the ‘radical Unitarian’ William Johnson Fox and his adoption of the pacifist doctrine of ‘non-resistance’, which in turn had led to a split with the Chartist George Julian Harney, an ally of Engels, over the question of the Krakow Rebellion in February 1846 and support for Polish national determination.

Duncan Hamilton (University of Manchester) examined other aspects of the life and ideas of Thomas Cooper, centring his presentation of Cooper’s early novel Captain Cobler. The paper looked at how Cooper’s work responded to both the elite medievalism of Augustus Pugin and others, and to the contrasting subaltern medievalism developed by authors such as William Cobbett in his History of the Protestant Reformation and others.

Hamilton argued that Cooper also uses medievalism as a way of thinking about the problems facing the Chartist movement, in particular in its pioneering use of ‘hospitable spaces’ as a narrative device that offers a contrast to the polemical diatribes found in later Chartist novels by Thomas Martin Wheeler and Ernest Jones. He concluded by considering the relationship between Captain Cobler’s communitarian vision and other examples of Chartist medievalism to demonstrate the politically ambivalent nature of a model that constructs medievalism as both nostalgia for a lost communitarianism and as a utopian vision of the Chartist world to come.

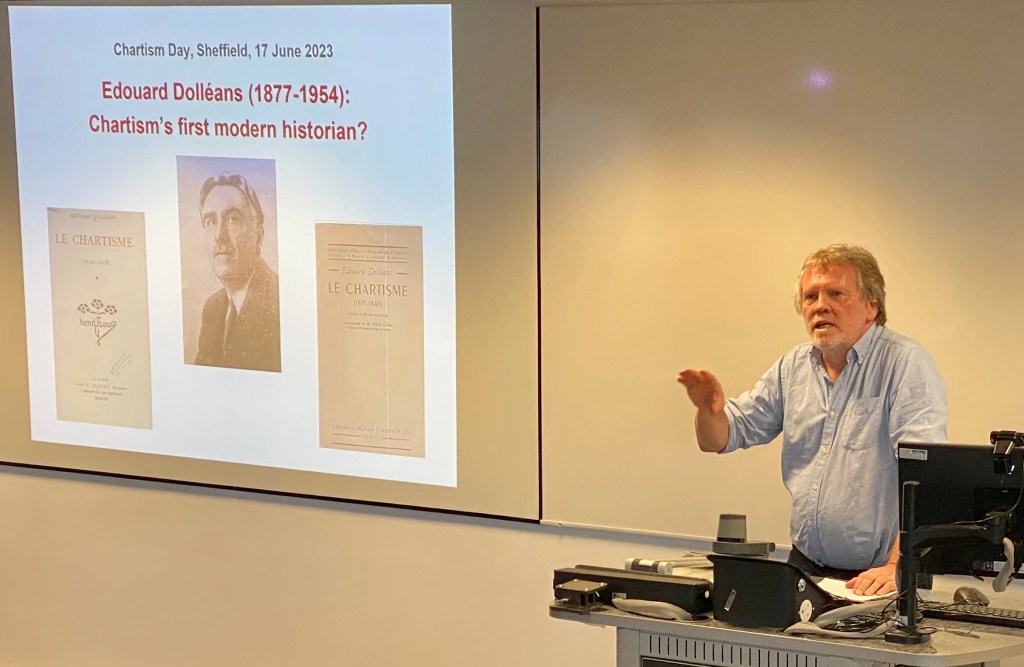

Professor Kevin Morgan (University of Manchester) discussed the work of the French historian and activist Edouard Dolléans (1877-1954), whose book Le Chartisme, originally published in 1912, was the first large-scale treatment of Chartism since R. G. Gammage’s The History of the Chartist Movement of 1854 (and updated by him in the 1890s). It was also the first work on the subject by an author and historian who had not been directly involved in Chartism.

Although the book was little known in this country, Professor Morgan speculated that the existence of a foreword contributed by the Fabian socialist Sidney Webb may well suggest that an English-language publication was planned, but abandoned due to the outbreak of war in 1914. And he argued that, by beginning his account in 1930, at a time of revolution in France, Dolléans thought of Chartism within an international context – British workers having all but invented such social movements before ceding their development to workers elsewhere in Europe.

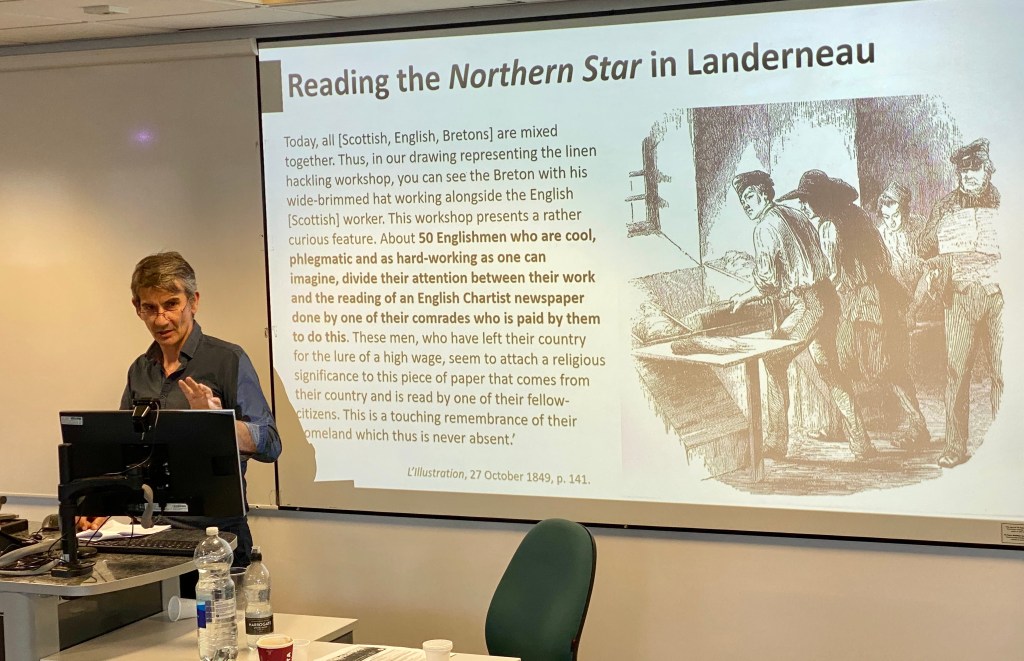

The final paper of the day was delivered by a contemporary French historian of Chartism: Professor Fabrice Bensimon (Sorbonne Université, Paris – Institut universitaire de France), who drew on his recent book Artisans Abroad: British Migrant Workers in Industrialising Europe, 1815-1870 to present the stories of British Chartists who took their political organisations and ideals with them as they moved to France to find work.

Professor Bensimon talked first about the Gloucester Chartist Thomas Sidaway and his son John, who in the mid 1840s ran the Nailors’ Arms pub in Rouen – a haven for British workers in the area, and effectively the home of the Chartist land company in France. Of the 43,000 known subscribers to the company, 104 were living in France, including in Calais and Boulogne, among them a number of Dundee jute workers.

Although British workers in France were unable to continue their political activities in the same way – not least because French laws on assembly were far more restrictive – they remained in touch with one another and with events at home through social activities, and through practices such as the reading-out-loud of the Northern Star to workers as they performed their jobs.

Professor Bensimon also told the story of George Good, born in 1824, a printer who was living and working in Paris at the time of the revolution of February 1848. George was the son of John Good, a Brighton Chartist who had been involved with Bronterre O’Brien’s Southern Star newspaper. George Good was among the crowd which, on 24 February stormed the Tuilleries Palace, leading to the abdication of King Louis Phillipe. Good, however, received a musket ball in his side, and died two days later.

Good is among the 202 victims of the revolution interred alongside the larger number killed in the insurgency of 1830 beneath the monumental July column at the centre of the Place de la Bastille.

Further reading: Artisans Abroad: British Migrant Workers in Industrialising Europe, 1815-1870, Oxford University Press (2023). Available on open access (without charge) as an ebook.

The day came to an end with thanks to the Society for the Study of Labour History, which provided funding, to Matthew Roberts for hosting the event, and to those on the organising group. Details of Chartism Day 2024 are… to be confirmed.

Chartism Day 2023 was dedicated to the memory of Stephen Roberts (1958-2022)

- The full programme is available as a PDF file here.

- Asbtracts of speakers’ papers are available as a PDF file here.

- Our thanks to Northern Herald Books for the book stall.

- Read our report on Chartism Day 2022.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.