Patrick Renshaw, who has died aged 87, began his academic career with a series of well-received books on trade union and labour history, and went on to teach American Studies at the University of Sheffield for nearly thirty years, turning his hand to significant and enduring works on US labour and political history.

Born in West Ham and educated at Wanstead County High School, Renshaw gained an open exhibition to study history at Jesus College, Oxford, and after graduating in 1959 won a Rockefeller fellowship. However, in 1961 he left the academic world for a job as a reporter on the Oxford Mail, where he remained until 1968 (serving for a time as treasurer of the local branch of the National Union of Journalists). That year, he gained a job at the University of Sheffield on the strength of his first book, The Wobblies: The Story of Syndicalism in the United States (1967). With brief spells at US universities, including a Fulbright fellowship in 1971-72, he remained at Sheffield as lecturer, senior lecturer and reader until his retirement in 1996.

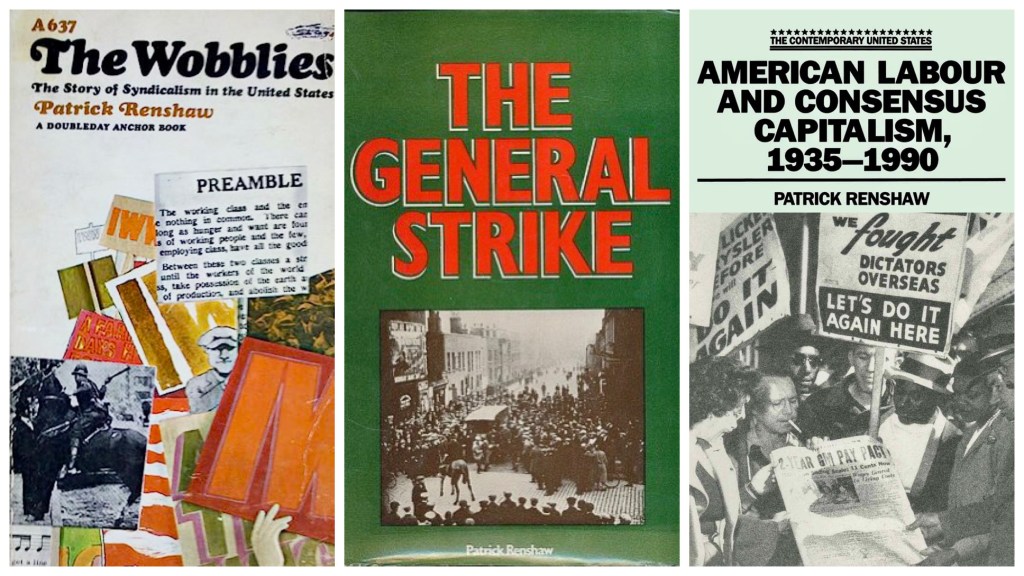

In addition to his work on the Wobblies, Renshaw was the author of the well-received The General Strike (1975). But much of his published work focused on US labour history and politics, including books on American Labour and Consensus Capitalism, 1935-90 (1991) and a critical biography of US President Franklin D. Roosevelt (2004).

Obituary in The Guardian (6 June, 2023).

Tribute

Emeritus Professor Keith Laybourn, President of the Society for the Study of Labour History, writes:

Patrick Renshaw was one of the leading labour historians of his generation. I first came across him in the late 1960s when I read his first book, The Wobblies, which led me temporarily into American history. He had a racy academic style of writing which appealed and which taught me about the activities of Daniel De Leon and Joe Hillstrom, whose execution for a murder he could not have committed led to the poem and song ‘I Dreamt I Saw Joe Hill Last Night’, which was later performed by Joan Baez on the imprisonment of her husband in the 1960s age of protest against Vietnam. His revelation of protest and suppression in America resonated with the protest movements of the 1960s.

He then again came to my attention in the 1970s when he did a series on television about the General Strike, which was presented day by day, in May 1976 I presume. About that time I read his book, The General Strike, which was a beautifully balanced analysis of the conflict between the government demand to drive wages down and the TUC defence of those wage, in which the battle lines were drawn over the move to reduce the wages of coal miners and worsen their conditions. It was brilliant and clear analysis of events, although I was alarmed when he started the book with the statement that coal was found in Britain by the Romans. I thought that this was likely to be a very long long-term origins of the General Strike, but that was not to be.

I agreed with most of his analysis – with the TUC being a reluctant organiser of the dispute, and the miners being ignored in the negotiations that led to the end of the dispute. Indeed, my father, a miner, endorsed some of his findings. When I asked him about the TUC leadership his only response was, ‘Never liked Jimmy Thomas, saw him and thought he was a traitor!’ The fact is, of course, this was part of a miners’ narrative, which he picked up in youth, since he was not born until 1924.

Whilst accepting much of Patrick’s argument, I could not accept his suggestion, along with many other writers, that the General Strike was a disastrous event which set back the trade union movement for a generation. I rather supported Hugh Clegg’s interpretation that it was also a warning shot to employers, who after 1926 slowed down their assault on wages and were quick, as was the National Government, to re-instate the trade union leaders, with Walter Citrine, Assistant General Secretary and Acting General Secretary of the TUC in 1926, being knighted. The attempt to hobble the TUC, by the Trades Dispute and Trade Unions Act 1927, which banned sympathetic strike action and stated that the trade union political levy to Labour should be one of ‘contracting in’ rather than ‘contracting out’, was a failure.

I only met Patrick Renshaw on one occasion, in the mid-1990s, before his retirement, and found him to be a most generous and thoughtful man. He was admired by his peers and loved by his research students, two of whom I had previously taught for their first degrees. His sad death adds to the growing list of historians now lost who dominated labour history from the 1960s to the 1990s.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.