Did people in the eighteenth century use the word ‘fuck’ in everyday language? Quentin Outram looks at swear words in BBC Two’s The Gallows Pole: A true story of resistance, and questions their authenticity.

‘Get your fucking hands off me!’ says David Hartley as people struggle to help him and from there on the use of ‘fuck’ and ‘fucking’ rarely stops for more than a few moments. Comments under the line on BBC iPlayer have often objected to the language but others have supported it as something authentic either to ‘the North’, or to the period, or to people generally. The trouble is that it’s not authentic to the period and it transposes the language of the First World War and later to the eighteenth century.

‘Fuck’, the word itself, has been around for a long time, at least since the fourteenth century. The earliest known instance where it may refer to sex occurs in English court records of 1310-11 where a man is referred to as ‘Roger Fuckebythenavele’, which experts think was possibly a nickname used to indicate a man or boy so stupid he couldn’t see how to have sex. Possibly before this (or possibly not) it was known in the context of ‘windfucker’, a delightful name for the kestrel, possibly using ‘fuck’ to mean ‘to beat’, or ‘to strike’ [the air], and ‘fuckwind’ which the Oxford English Dictionary says is a northern regional term (there’s that insistence that Southerners don’t use such words again) for ‘a species of hawk’. As ‘hawk’ may or may not mean ‘a bird used in falconry’ and as kestrels are sometimes used in falconry ‘windfucker’ and ‘fuckwind’ may have been synonyms.

This all seems to let The Gallows Pole off the hook, but the trouble is there is no indication that ‘fuck’ was much used as a swear word before the twentieth century. Before this the ‘older profanity’, based largely on blasphemy, held sway: ‘bloody’ (possibly from ‘God’s blood’), ‘damn’, and ‘hell’. The first generally known example of ‘fucking’ in print is in J. S. Farmer and W. E. Henley’s, A Dictionary of Slang and its Analogues, published in seven volumes, for subscribers only, between 1890 and 1904. The editors defined ‘fucking’ as a ‘qualification of extreme contumely’ and ‘a more violent form of BLOODY’. Although they described it as ‘common’ they were, understandably, unable to support this claim from printed sources. The wide variety of offensive and pejorative compounds they note (eg. ‘fuckable’) may suggest that the root word had been long established but the rapid and relatively recent efflorescence of new compounds such as ‘motherfucker’, infixed terms such as ‘fanfuckingtastic’, and ‘nonce variations’ such as ‘fuckity’ or ‘fuckety’ suggest that such developments are no sure attestation of any great longevity.

Instead we can assemble two sets of evidence. One is the use of euphemisms. Richard Aldington’s, Death of a Hero, first published in 1929, but based on his experiences of the First World War, uses ‘mucking’ and variants as an unmistakable and frequent euphemism for ‘fucking’ and its variants. The language intensifies as the book progresses and towards the end one character says: “ ‘I told that muckin’ new orfficer twice that some mucker’d get hit if he muckin’ well took us up that muckin’ trench.’ ”. Climactically, two pages later, an officer is told to “ ‘Muck off!’ ”. Robert Graves, again writing of the First World War in Goodbye to All That, also first published in 1929, used ‘eff’ as his euphemism, and did not feel able to relinquish it even on his revision of the book published nearly thirty years later. One instance he recalled from 1917 concerned Boy Jones who had somehow managed to enlist though he was only 14 (and, wrote Graves, looked only 13) who was put on a charge for using obscene language; he had called a bandmaster ‘ “a double effing c—” ‘.

It is very hard to find such euphemistic references to ‘fuck’ and ‘fucking’ much before the First World War and very hard to find them before about 1890. The digitization of many local newspapers in recent years has enabled the search but the results are meagre. The first I’ve found is from 1875 and is a report of proceedings at the police court in the Nottinghamshire Guardian for 24 September 1875:

Frederick Rogers, was charged with being drunk at Lenton on the 14th September. –P.c. Dobson stated the charge.—Defendant said he saw the officer talking to a servant girl at a third storey window, and he said to him he thought it would be better if he would go about his duty instead of “mucking” about like that, and the officer immediately made a reply that he would show him what his duty was.—He called his wife to support this statement, and after hearing her the Bench discharged the defendant.

It’s only the constable’s reaction and the reporter’s use of inverted commas which reveals that ‘mucking’ is a euphemism and that the underlying language was regarded as offensive. I’ve not found another usage like that until 1905 (see ‘Diplomacy in the dock’, The Globe, 18 July 1905, p. 2).

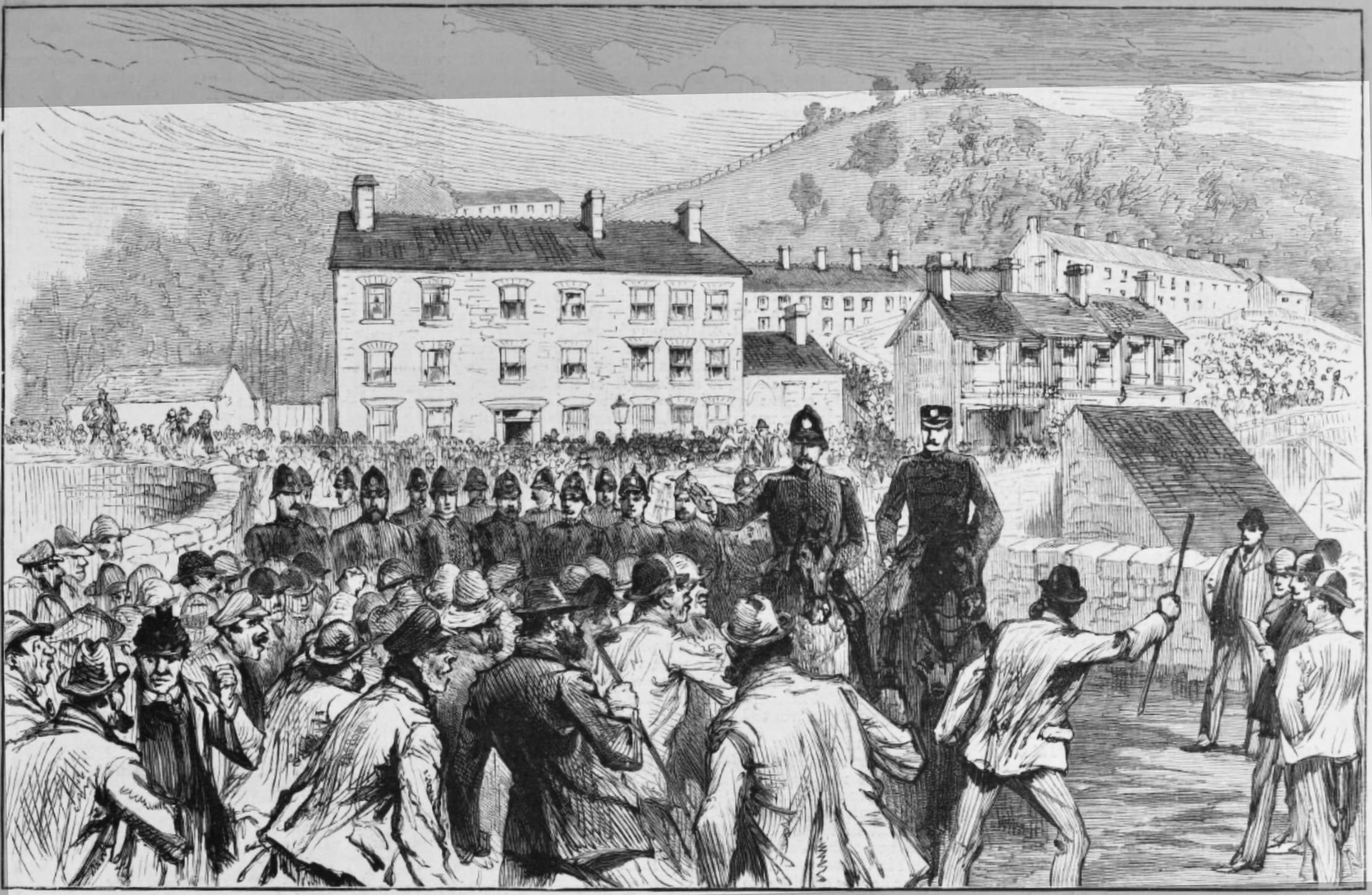

The second set of evidence consists of absences. We can look for reports of language that we would expect to contain swearing and obscenities and see what we find. In many instances reports and other texts are bowdlerized of course but the devices employed, for example the substitution of ‘b—-y’ for ‘bloody’ would defeat only the entirely innocent. However, some instances are less transparent and some, ‘*******’ for example, entirely opaque. So it would be preferable to find texts that were verbatim, perhaps because they were written for a limited (and typically strictly male) audience, for example texts written to inform legal and quasi-legal proceedings. One example I have found consists of the depositions of evidence gathered by the Treasury Solicitor’s department for the Committee of Inquiry into the ‘Featherstone Massacre’ of 1893, a disturbance which turned to anger and at which soldiers shot two miners dead. This evidence was never published.

The days before the shootings at Featherstone had been full of often tense and angry encounters between strikers, colliery managers, and working miners as renewed efforts were made to stop all work in the pits. The day of the massacre saw several hours in which police, soldiers, miners and their wives and children were at a stand-off and this period was noisy with hooting and jeering and shouting. If we were to hear ‘fucking this’ and ‘fucking that’ in the late nineteenth century we would expect to hear those words here. (Those convinced of the enduring politeness of southern speech will also be pleased to note that, except to those from the North east for whom ‘the South’ starts at the River Tees, Featherstone is indubitably in ‘the North’; it is, indeed in Yorkshire, though some way east of Cragg Vale.)

The strength of feeling was unmistakable. A couple of days before the massacre a group of men still working on the surface at Ackton Hall Colliery in Featherstone, loading coal into railway waggons, were told ‘If you don’t give over we’ll knock y[our] bloody ribs in’. The next day in another encounter, a group of strikers used ‘very strong’ language to the men’s surface foreman, William Jaques, telling him that if he went near the coal they would ‘tear him from limb to limb’. Jaques told the strikers he was not loading coal at all; they retorted ‘it was a b[loody] lie’. ‘The language used to us was awful,’ said Jaques. Early in the evening of the following day, after soldiers had arrived in Featherstone, a deputation of five men from the crowd surrounding the colliery approached A. J. Holiday, the manager, and demanded that he remove the police and soldiers at once. If he did so, they said, all would be quiet; if he did not, then he must take the consequences. When Holiday told them he had no power to do so, the crowd ‘got very menacing’. The deputation turned to the crowd and told them to wait but they shouted out their demand to remove the police and soldiers; Holiday again said he had no power to do so. Then several shouted “Kill him! Kill the bugger while you have him!” Then the magistrate, Bernard Hartley, finally arrived. Again, there were cries of ‘Take away the soldiers’. Hartley told the crowd that if they did not leave he would have to read the Riot Act. ‘Several shouted out “Read it you old bugger. If you don’t your [sic; you] daren’t.” ’ ‘ “Read your Bloody Riot Act[.] Shoot us[,] we don’t care” &c &c and hooting & yelling’, heard Holiday. The language, the awful language, as Jacques described it, is of ‘bloody’ this and ‘bloody’ that, of buggery, and murder, not of ‘fucking’ this and ‘fucking’ that.

It is absences such as this that make us confident that the fuckery of The Gallows Pole is inauthentic. It may be that the writer has to use such vocabulary to convey to the modern reader and viewer the characteristics of the language that was used at the time, to make it clear that Cragg Vale and its inhabitants were not living in the southern England of Jane Austen and her gentlemen and ladies. But this fits uneasily with what is said to be a ‘true story’.

Sources and Further Reading

The title refers to the well-known anecdote of British school teachers concerning a parent complaining to their child’s school about their child’s swearing. Its origins are in a story told by Leila Berg in Risinghill: Death of a Comprehensive School, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, 1968.

The Gallows Pole was broadcast on BBC Two on Wednesday 31 May. Watch the series now on iPlayer.

Geoffrey Hughes, Swearing: A Social History of Foul Language, Oaths and Profanity in English, Penguin, 1998, gives an excellent overview and I am indebted to him for the idea of the ‘Decay of the Old Profanity’.

For ‘Roger Fuckebythenavele’ and other early uses of ‘fuck’ see Paul Booth ‘An early fourteenth-century use of the F-word in Cheshire, 1310–11’. Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire. 164 (2015): 99–102. Further discussion and references are available from the Wikipedia article ‘Fuck’. Detailed dictionary entries are available from Wiktionary and from the Oxford English Dictionary Online.

J. S. Farmer and W. E. Henley, A Dictionary of Slang and its Analogues, 7 volumes, 1890 -1904 has been long out of print and complete sets are not often offered by antiquarian book dealers for much less than a thousand pounds. A cheap two volume edition was published by Wordsworth Editions in 1987 and second-hand copies of this are available for much less. The first edition is available online at The Internet Archive.

For the post-first world war literature and its attempt to reproduce soldiers’ language in euphemism see Richard Aldington, Death of a Hero, first ed. W. Heineman, London, 1929 (I have used the Phoenix Library edition, Chatto & Windus, London, 1930, and my quotations are from p. 364 and 366; there is a modern edition by Penguin, from 2013); Robert Graves, Goodbye to All That, Jonathan Cape, London, 1929 (a revised edition came out in 1957 published by Cassell and this is the edition that has been kept in printed by Penguin ever since.) Paul Fussell and others have mounted a sustained attack on the veracity of Graves’s book, arguing that it is best interpreted as a satire (Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1975, pp. 210-30). Fussell’s interpretation is doubtless correct but does not appear to undermine the use I have made of the book here; satire and reality are not necessarily distinct.

I have used the British Library’s British Newspaper Archive to search nineteenth century newspaper texts. Regrettably, a subscription is required.

The quotations given from the Featherstone disturbances are from (a) the official report into the disturbances, Report of the Committee Appointed to Inquire into Circumstances Connected with the Disturbances at Featherstone on the 7th September 1893 [Chairman Lord Bowen], C.7234, Parliamentary Papers, 1893-94, xvii, 381, and the Minutes of Evidence (with Appendices) taken before the Committee appointed to Inquire into the Circumstances connected with the Disturbances at Featherstone on 7th September 1893, C.7234-I, Parliamentary Papers, 1893-94, xvii, 399, and (b) the depositions gathered in Featherstone and the surrounding area for the Treasury Solicitor’s Department, now preserved at the National Archives (TNA TS18/1407).

The most recent scholarly published account of the Featherstone Massacre is by Carolyn Baylies in her History of the Yorkshire Miners 1881-1918, Routledge, London, 1993, pp. 95-130.

Quentin Outram is Secretary of the Society for the Study of Labour History.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.