In 1839, the radical London Chartist George Julian Harney was out on bail awaiting trial for sedition. Two letters to his lawyer reveal his anxiety about the case and his desperate lack of cash. Mark Crail tells the story of Harney’s anxious summer.

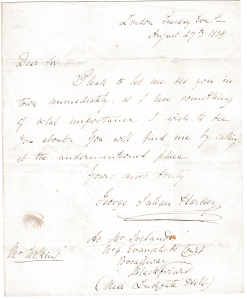

The letter shown here is filled with the angst of a man facing a possible gaol sentence and badly in need of his lawyer’s advice. Written by the Chartist George Julian Harney in August 1839, and addressed to a Mr Wilkins, the letter provides little detail of the topic Harney wanted to discuss, but its sense of urgency is clear in every word.

At the time it was written, Harney was on bail. The first of the great Chartist petitions had been put before Parliament on 14 June that year, and on 12 July, Thomas Attwood’s proposal that the petition be considered by the Commons was defeated by 235 votes to 46. The Chartist convention, sitting first in London and then in Birmingham, now moved to consider what ‘ulterior measures’ should be put into effect. The most contentious of these was the call for a Grand National Holiday – in effect a general strike. Proposed by the long-time ultra radical William Benbow and backed by Harney, this measure won the support of the convention despite warnings from Feargus O’Connor and others that it lacked backing in the country.

At this point, Harney set off for the North of England on a speaking tour, where he hoped to win the support of industrial workers for the strike. But after addressing a meeting at Bedlington in Northumberland, he was arrested for sedition.

Harney was still just twenty-two years old in 1839, but his was already a significant radical voice. The historian Dorothy Thompson has described his life as ‘central to the study of Chartism’.1 Born in 1817 at Deptford in Kent, he had been destined for the merchant navy, but instead found himself before the age of twenty working for Henry Hetherington, publisher of the Poor Man’s Guardian and a leading figure in the campaign against the ‘taxes on knowledge’. His political commitment had earned him three short prison sentences in the 1830s, but these had done little to temper his radicalism, and from the early days of Chartism, influenced by his Spencean allies in the London Democratic Association, he argued the need to arm and prepare to take power by force if necessary.

After his arrest in Bedlington, Harney was taken first to Carlisle, where a large crowd assembled in front of the inn where he was being held to demand his release. Harney himself urged them not to interfere, but eventually he had to be smuggled through the backdoor and into a waiting chaise to be taken to Birmingham. Robert Gammage noted: ‘His offence was the delivery of a seditious speech; that speech being one of the mildest he ever delivered.’2

At Birmingham, a grand jury found a true bill against Harney for ‘uttering seditious language’, and he was committed for trial at Warwick Assizes. At his first appearance before a judge on 7 August, he was released on bail, for which he was expected to put up £80, and two others £40 each (Northern Liberator, 10 August 1839, p5). Somehow, he managed to scrape the money together, and was released pending his trial. It is shortly after this that Harney writes to Wilkins.

Sent from an address at Blackfriars in London, the letter, dated 27 August 1839, urges Wilkins: ‘Please to let me see you in / town immediately, as I have something / of vital importance I wish to see / you about. You will find me by calling / at the undermentioned place.’ [/ indicates a line break in the original].

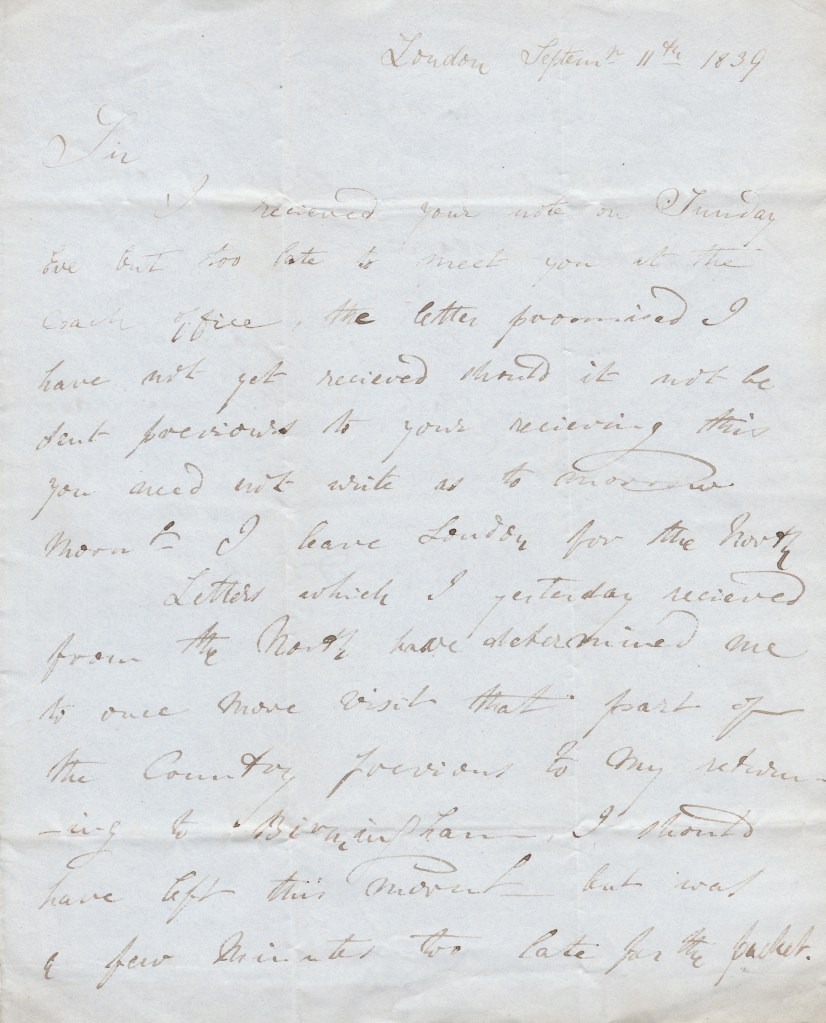

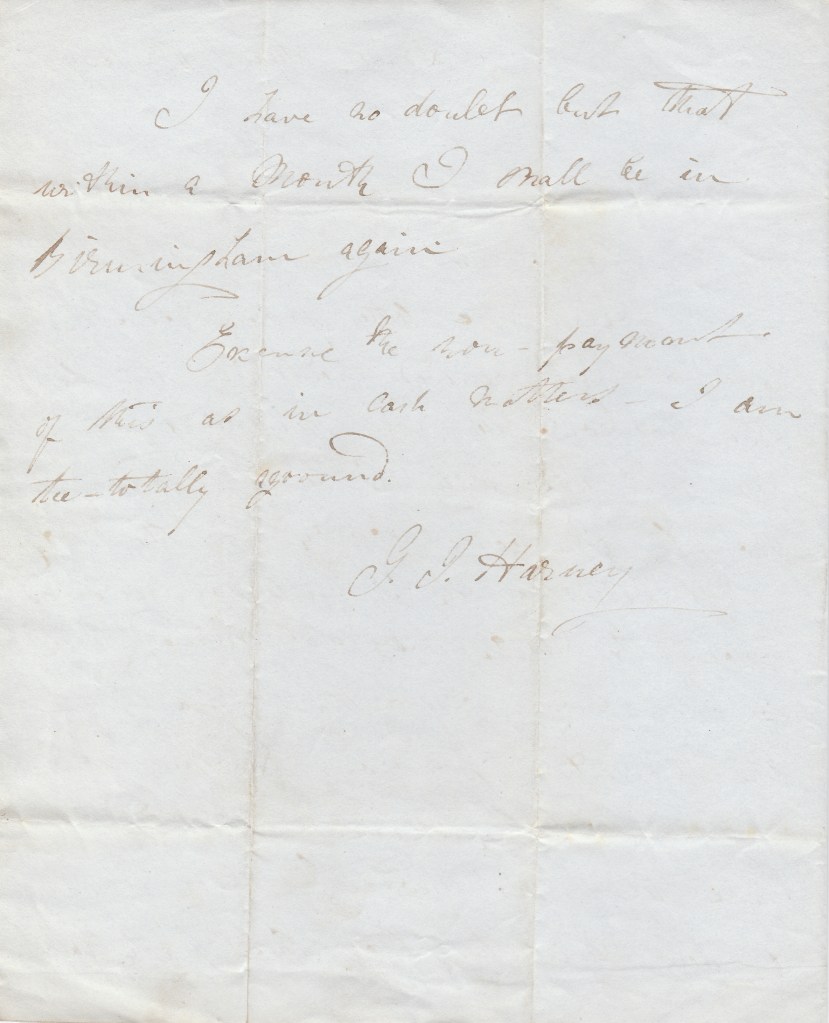

Whatever Harney’s desperation was at this point, it appears that no meeting took place. A second letter, shown in the image gallery below, and similarly addressed by Harney to Wilkins at his lodgings in the ‘Black Boy and Woolpack Inn, St Martin’s Lane, Near the Old Church, Birmingham’ is dated 11 September 1839. It opens: ‘I received your note on Tuesday eve too late to meet you at the coach office…’ He says Wilkins need not write to him in London as letters he had received from the North of England that morning ‘have determined me to visit that part of the country previous to my return to Birmingham.’ He adds: ‘I should have left this morning but was a few minutes too late for the packet.’ He concludes with a jokey apology for having failed to pay the postage on his letter: ‘Excuse the non-payment of this as in cash matters I am tee-totally aground.’

Whatever his reasons for heading back north, Harney managed to return to Birmingham in time for the next court hearing, and when the case eventually came up for trial in March 1840, the prosecution offered no evidence against him or his co-accused, Henry Wilkes, ‘it having been agreed that if, in the interim, they conducted themselves properly they should be acquitted’ (Globe, 3 April 1840, p2). Others were not so lucky. Many of those accused of offences relating to the convention had already been sent to prison, and while Harney and Wilkes were able to walk free, Edward Brown, who had been a Birmingham delegate and was in court alongside them, was convicted of sedition and imprisoned for eighteen months.

After his legal ordeal, Harney went to Scotland where he married, before returning to Yorkshire the following year to work first as a local correspondent for O’Connor’s Northern Star and then, from 1843, as sub-editor. He would go on to edit the Star from 1845 until he again fell out with O’Connor and launched his own Red Republican newspaper at the end of the decade. When the Star had moved to London in 1844, Harney also established the Fraternal Democrats, an organisation in which, in two iterations, he built links with European radicals, including the French socialist Louis Blanc and the Germans Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, and created a Left faction within Chartism, arguing for a socialist position, ‘the Charter and something more’.

Although Harney’s internationalism later evolved into a less attractive and somewhat jingoistic patriotism, he and Engels would remain on friendly terms and continued to correspond until the latter’s death in 1895. Harney himself died in 1897.3

The identification of Wilkins, the recipient of the letters, as Harney’s lawyer is by no means certain. However, a barrister by that name featured in a number of reports of Chartist trials in the Northern Star. On 30 March 1839, when Joseph Rayner Stephens was on bail awaiting trial, a barrister named Wilkins appeared at South Lancashire spring assizes on his behalf (NS, 6 April 1839, p8). Later that same year at Lancashire County Sessions, Wilkins represented four men accused of being part of a group of more than thirty Chartists accused of attempting to enforce a general strike for the Charter at Wigan (NS, 16 November 1839). And early the following Spring, a Mr Wilkins represented five Bradford Chartists charged with conspiracy to riot (NS, 21 March 1840, p8). In the absence of better candidates, this would seem to be Harney’s most likely correspondent.

Sources and further reading

1. The Dignity of Chartism: Essays by Dorothy Thompson, edited by Stephen Roberts London: Verso, 2015

2. History of the Chartist Movement 1837-1854 by Robert Gammage, second edition 1894; reprinted by Augustus M Kelley, New York, 1969.

3. ‘Harney and Engels’, by Peter Cadogan, in International Review of Social History, vol. 10, issue 1, April 1965 , pp. 66 – 104. Available online.

All newspaper reports cited above are taken from the issues in the British Newspaper Archive.

Both letters are in the possession of the author.

Mark Crail is web and social media editor for the Society for the Study of Labour History. He also runs the Chartist Ancestors website.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.