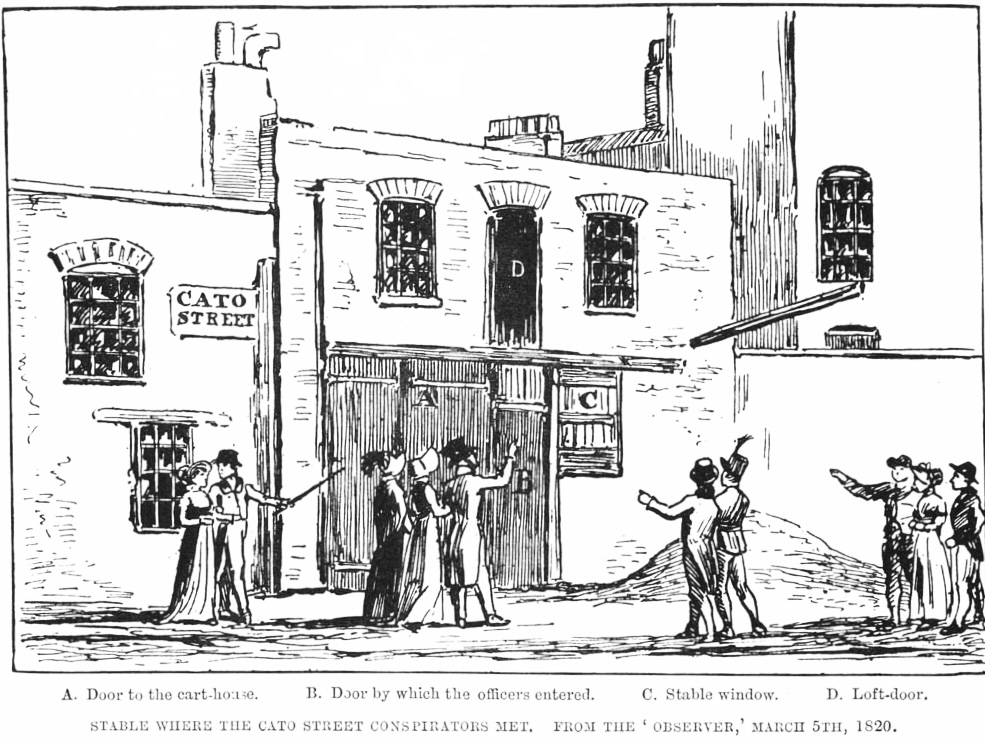

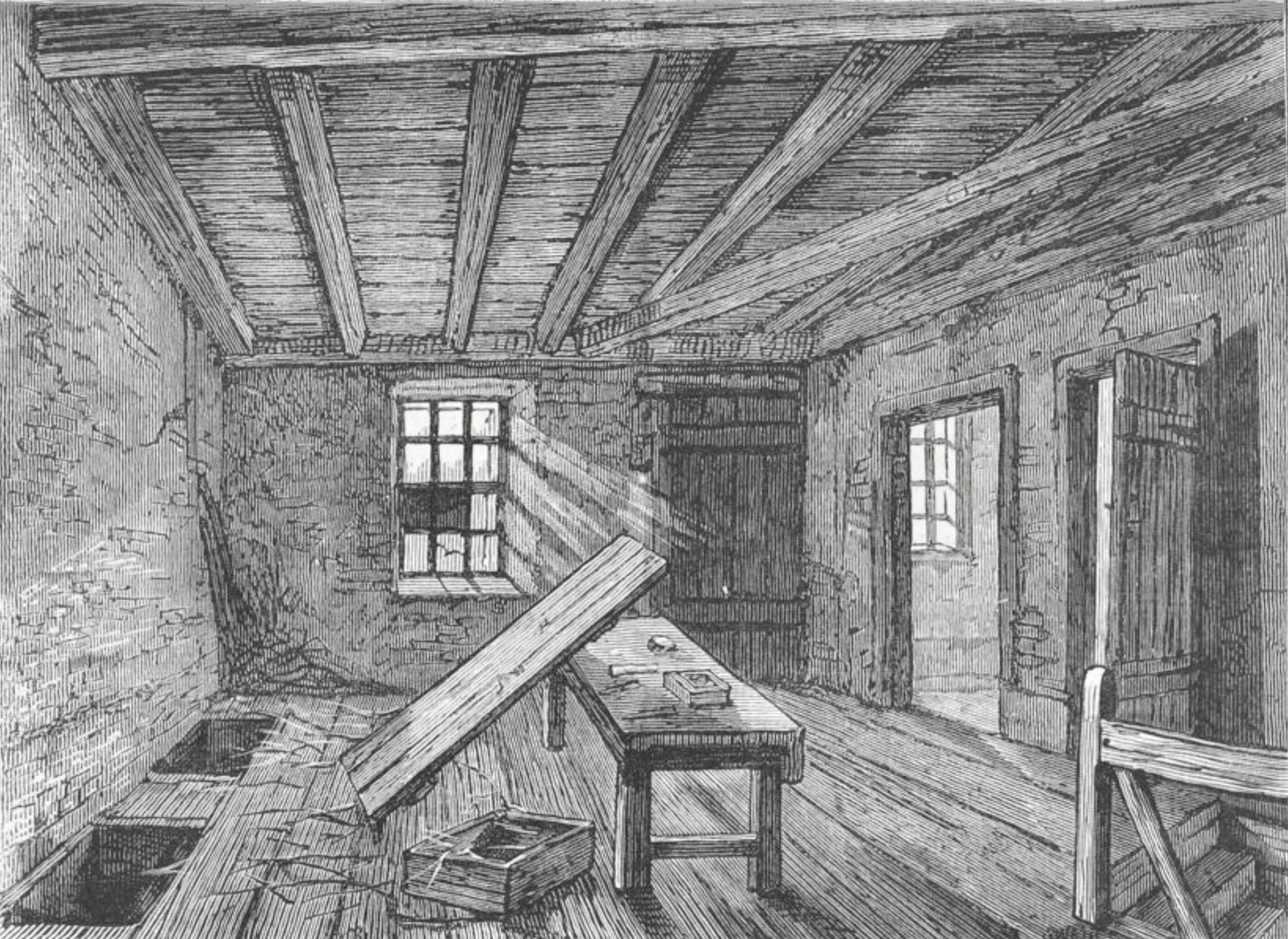

The picture above shows the former stable in which London’s ultra radicals met in 1820 to plan the murder of the Cabinet and the installation of a provisional government. From the outside, the building in Cato Street, now an expensive residential area close to the busy Edgware Road, appears much as it did two hundred years ago (see below). But behind the blue plaque on the façade, much has changed. The upper entrance to the hayloft has long since been bricked up; the double stable doors are purely for show, concealing a new wall; and where horses were kept and the impoverished insurrectionaries once met, there is now a small but highly desirable two-bedroom house.

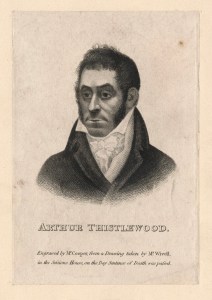

The revolutionaries of 1820 took their inspiration from Thomas Spence, a former school teacher from Newcastle who had established himself in London in 1792 as a publisher and seller of radical books, pamphlets and newspapers, including his own periodical, Pig’s Meat. Spence persisted despite regular periods of imprisonment, and came to be at the centre of a network of revolutionary ultra radicals. Following his death in 1814, his comrades formed the Society of Spencean Philanthropists to continue his ideas and work. Many of those who came to be involved in the Cato Street conspiracy, including its leading figure, Arthur Thistlewood, were part of this group.

Two years later, in 1816, the Spenceans succeeded in persuading Henry Hunt, already a well-known radical speaker, to address two meetings at Spa Fields in Islington demanding electoral reform and relief for the poor. They hoped – and planned – for the rallies to lead to rioting during which they would be able to seize the Tower of London and the Bank of England, fuelling a wider insurrection and the overthrow of the government. Although successful in fomenting disorder and managing to raid a gun store for weapons, the Spenceans failed utterly in their wider aims and alienated Hunt and others. Four leading Spenceans, including Thistlewood, were subsequently arrested and charged with the capital offence of high treason; but when the first case came to court, the evidence of a government spy was discredited, the case collapsed and all four men walked free.

Undeterred by their brush with death, the Spenceans continued to organise and agitate. Police spies reported that Robert Wedderburn, the black son of a Jamaican slave, had now emerged as the group’s leader, and that from the pulpit of his Unitarian chapel he was giving ‘violent, seditious, and bitterly anti-Christian Spencean speeches’. Outraged by news from Manchester of the Peterloo massacre, in October 1819 Wedderburn was said to have proclaimed that the revolution was about to begin and all working men ‘should learn to use the gun, the dagger, the cutlass and pistols’.

With Wedderburn in prison and waiting trial for blasphemy, however, it was Thistlewood who now took things forward. In light of later events, Wedderburn may have considered his arrest to have been a piece of good luck. Over the autumn and winter of 1819, Thistlewood became convinced that a relatively small group of committed ultra radicals could seize and kill the prime minister, Lord Liverpool, and his ministers, form a provisional government under a committee of public safety and spark a nationwide revolution. From among the ranks of the Spencean Philanthropists and others driven to revolution by poverty, hunger and outrage at the political and social injustices of the time, Thistlewood gathered a group to carry his plan into effect.

Unfortunately for Thistlewood and his supporters, their number included a government spy by the name of George Edwards, and at the behest of the authorities he would steer the Spenceans to their doom. On 22 February 1820, Edwards arrived in Cato Street with news that the entire government would be assembled the following night at the home of the Earl of Harrowby. In fact, this was a trap and no such assembly was planned; but Thistlewood was taken in, making plans to march his men the following night the short distance from Cato Street to Grosvenor Square. His closest allies were now allocated key roles in the planned assault – rushing the front door, holding back Harrowby’s servants, and killing the Cabinet as they dined. James Ings, a former butcher, volunteered himself for the grisly task of beheading the murdered prime minister in order to parade the grisly trophy through the city as the signal for a wider uprising.

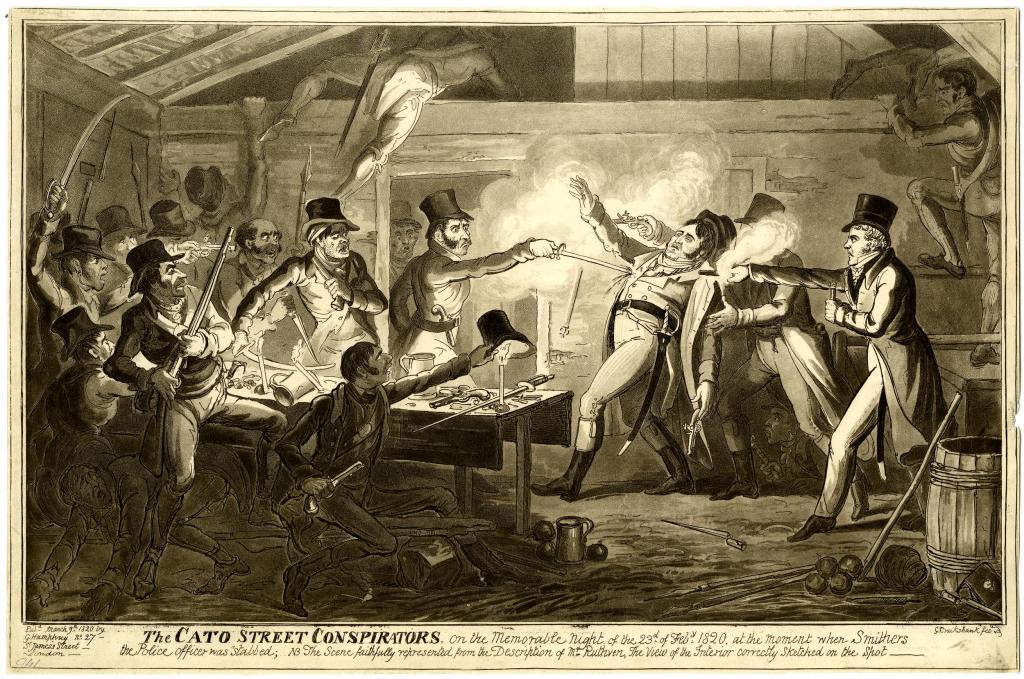

The following day, as the Spenceans readied themselves for the rising in the upstairs hayloft at Cato Street, a contingent of Bow Street Runners were waiting in a public house on the opposite side of the road. When a troop of Coldstream Guards failed to turn up to storm the building as planned, having got lost on the way, the Bow Street Runners did the job themselves, swarming through the doors and up a narrow staircase to surprise the conspirators.

In the melee that followed, Thistlewood drew his sword and killed a Bow Street Runner. Some of the conspirators were captured after a fight; others surrendered peacefully; and still others, including Thistlewood, escaped through a rear window. They were arrested within days.

Eleven men were charged for their part in the conspiracy. The cases against two more, Robert Adams and John Monument, were dropped when they agreed to give evidence.

All eleven defendants were found guilty of high treason and were condemned to the barbaric punishment of hanging, drawing and quartering. The sentences against John Harrison, James Wilson, Richard Bradburn, John Shaw Strange and Charles Copper would be commuted to transportation. James Gilchrist would have his sentence entirely remitted and he would walk away a free man, having been caught up in events of which, it transpired, he had little understanding. But the mercy shown to Arthur Thistlewood, William Davidson, James Ings, Richard Tidd, and John Brunt was to be somewhat less generous: their punishment was reduced to death by hanging followed by the beheading of their corpses. On the morning of 1 May 1820, the sentence was carried into effect in front of a huge crowd outside Newgate Prison. It was, by all accounts, an awful and bloody scene. And it spelled the end of the Spencean Philanthropists.

Back in Cato Street, number 1, where the plot was hatched, is now the only surviving building from the period. The pub where the Bow Street Runners watched and waited, and much of the remainder of that side of the street, is now modern housing. At the time of writing, individual two-bedroom flats there are on sale at £860,000, while a four-bedroom townhouse in the development has a price tag of £2.3 million.

Number 1 Cato Street itself has been a Grade II listed building since 1974 because of its association with the conspiracy; in 1977, the Greater London Council added the blue plaque.

And thanks to the modern obsession with house prices, it is possible to see photographs of the inside of number 1 as it is now, or at least, as it was when the property went up for sale in 1995. It is still easy to identify the place where Thistlewood took his final stand and where the unfortunate Bow Street Runner met his death; but it is harder to match the horrors of that day in 1820 with the cosy domesticity of the later scene.

Further reading

Conspiracy on Cato Street: A Tale of Liberty and Revolution in Regency London by Vic Gatrell, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022, is an illuminating and highly readable account of the conspiracy and the conspirators.

The Cato Street Conspiracy: Celebrating the Bicentenary of the West End Job is an excellent website created by the Westminster Community Reminiscence and Archive Group with a grant from the Heritage Fund. It includes impressive virtual reality re-creations of the insides of both the barn and the Earl of Harrowby’s house, and additional resources on William Davidson, a black Londoner and one of those executed.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.