At any other time, a few hundred manufacturing workers calling a strike over pay would hardly merit much more than a footnote in the history books. But the dispute at Silentnight’s bed factories in the mid 1980s was a pivotal moment in industrial relations – and, for trade unions and their members at least, this was a clear warning of the difficult times to come.

The dispute began when members of the Furniture, Timber and Allied Trades union agreed to forego a wage rise in return for the promise that there would be no job losses. Soon after, in June 1985, Silentnight founder and boss Tom Clarke reneged on the deal and sacked 52 employees. Workers at the company’s Barnoldswick (Lancashire) and Sutton-in-Craven (West Yorkshire) factories walked out – and a further 346 were sacked for taking part in the strike.

The strike was significant for three reasons. First, because the National Union of Mineworkers’ defeat just a few months earlier at the end of the 1984-85 dispute appeared to signal a new era of industrial relations in which employers were to be in the ascendent and trade unions’ ability to defend their members was weakened. What happened at Silentnight provided bitter confirmation of this.

Second, because Clarke was no run-of-the-mill factory owner. Reputed at the time to be the UK’s highest paid executive, he was also a committed Conservative, dubbed ‘Mr Wonderful’ by prime minister Margaret Thatcher for his support. For those at the top of government, this was personal as well as political.

And third, because of the sheer length of time that the Silentnight workers maintained their defiance. Said to have been Britain’s longest ever strike (though this is contested), it was only in April 1987, after 616 days on the picket line, during which their caravan headquarters had been firebombed, that FTAT members recognised that their cause was lost and called an end to the strike.

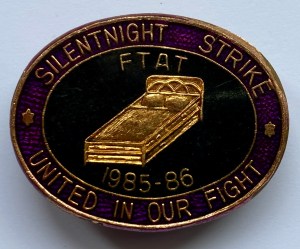

Over that two years, the labour movement had rallied behind the strikers. Labour MPs visited the picket lines, and the local party provided office space after the arson attack. Badges, including the one shown here, were sold to raise funds and commemorate the events of 1985-1987. But in the end it was not enough.

Today, Tom Clarke is long dead and the company he founded has moved out of family ownership. The company continues to make beds in Barnoldswick, but its Sutton factory closed in 1994. FTAT merged with the GMB in 1993. The stories of some of those involved in the strike have been told in both newspaper and academic accounts.

Further reading

What came after the longest strike in history was finally put to bed is a retrospective account of the dispute in the local Craven Herald newspaper which a number of those who went on strike are interviewed.

‘Dismissal of strikers and industrial disputes: the 1985–1987 strike and mass sackings at Silentnight’ by Stephen Mustchin, published in Labor History, 55:4, 2014 analyses how the dispute was sustained, its legal context, and the networks that arose around the strike.

The last battle for Barnoldswick, by Sam Stroud appeared in Tribune in February 2021 following a later successful strike by Rolls-Royce workers in the town

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.