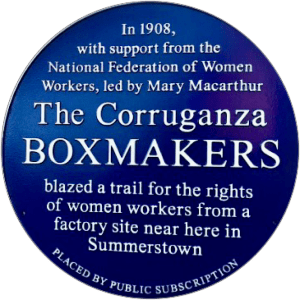

As plans come together to unveil a blue plaque marking the Corruganza boxmakers’ strike of 1908, Geoff Simmons explores a dispute that helped Mary Macarthur hone the campaigning skills she would bring to future disputes.

In the summer of 1908, 44 young women at the Corruganza box factory in Summerstown, south west London came out on strike in response to a pay cut in the firm’s tube rolling, cutting and gluing department and the dismissal of a forewoman who had raised objections. A young, largely uneducated group whose actions would have been at great personal risk, they were very quickly supported by Mary Macarthur and the recently formed National Federation of Women Workers. Within a month, the strike was over, the women were reinstated and apart from a small deduction in one area, rates returned to what they were before. And for Mary Macarthur this had been a chance to deploy the tactics which would be used to help women in future actions at Cradley Heath and Bermondsey.

This was a poor area and work at the factory on the banks of the River Wandle was irregular, so reductions of up to 50 per cent would have bitten deeply. Box making was traditionally a home-industry but recent advances had increased mechanisation, making for a dangerous environment where injury was always a possibility: mutilated hands, sickness and exhaustion caused by manipulation of heavy machinery or the stench of warm glue. Some of the workers were as young as 12 or 13.

As Mary Macarthur cranked up the publicity, details of the exchanges and discussions were covered in the local and national press. Mary’s own channel was The Woman Worker. Here she defined the pay cut as an attempt by the newly promoted owner’s son to impress his father by replacing troublesome workers with younger girls who he could pay less. Hugh Stevenson had established his first box factory in Manchester in 1859 and the Summerstown works from around 1896 on the site of the Garratt Printworks, an old calico mill. The name ‘Corruganza’ adopted in 1900 reflected the popularity of relatively new corrugated board. By 1914 the company employed 2,610 workers.

Mary’s passionate amplification of the strikers’ cause saw donations flood in, enough to provide them each with five shillings a week relief. The highlight of the campaign, plotted largely in Jerry’s Coffee Tavern on Garratt Lane, was a fundraising march to Trafalgar Square. They had a song to sing along the way:

'If you can’t do any good, don’t do any harm; Live and let live, we all know that’s a charm. Doing good for evil – it’s a saying old but true, Take my tip- it’s the finest thing to do! I know – you know, quite as well as me, It's no use bearing animosity. If you have an enemy, try his faults to smother. We’re all as good – as good as one another!'

Speakers that day included the shopworkers’ union official and later the first ever woman Cabinet Minister Margaret Bondfield, and Herbert Burrows, a key organiser in the Bryant & May match workers’ strike, as well as some of the boxmakers themselves. A set of printed postcards of the occasion helped bolster the strike fund and give an insight into some of those involved. Although the names of the great majority of the 44 are unknown, for fear of repercussions, some get a mention on the pages of The Woman Worker. There are Polly Cambridge and Annie Willock who spoke at the event; Alice Chappell who needed great physical strength to work as a roller and was crudely referred to by the Stevensons as ‘The Battersea Bruiser’; 14-year-old Mike Smith who heroically refused a management offer to replace a striking worker; and Mary Williams, the sacked forewoman who was eventually offered her job back but declined. Mary Macarthur crucially also made sure that key Corruganza clients, Cadbury and the Cooperative Wholesale Society, were notified of the dubious labour practices in Summerstown.

Discussions with the Board of Trade resolved the dispute fairly swiftly. Sophie Sanger who went on to have a distinguished career as a labour law reformer and became the first woman Section Chief of the International Labour Organization, represented the strikers. Clearly the reputation of the Corruganza had taken a knock. By 1920 the company had reverted to calling itself Hugh Stevenson & Sons and it seems there was further unrest around that time. A fire in 1924 caused extensive damage to the site and 600 workers were temporarily laid off. Despite this they remained a major employer in the area for over six decades and further changes of name. Their own publicity material includes film footage from 1937 that portrays a community-focused organisation and a contented workforce enjoying lunch-breaks on the banks of the Wandle, excursions to Brighton and lots of sport and social activities. Older local residents have memories of the firm’s boxes being used to salvage people’s belongings from bombed houses.

I came across this story when was doing a local First World War commemoration project, and in going over 1911 census records noted how many people, especially women, worked as ‘fancy box makers’ or were employed at the Corruganza Works. If they didn’t work at one of the numerous laundries in the area it was very likely they were at the box factory. I soon came across Bronwen Griffiths’ online account of what happened there, first published in the book For Love and Shillings thirty years ago.1 But there was very little else about it. I started featuring the story on my Guided Walks, particularly when Mary Macarthur made the news with a blue plaque on her home in Golders Green. We also had a visit from Macarthur’s biographer Cathy Hunt who delivered a talk at a local theatre. So many people had a relative who worked at the factory, and it was around in some form until the 1980s but no one seemed to have heard about the strike.

The story of the courageous young women who took on a powerful opponent in the summer of 1908 needs to be more widely known and we will be unveiling a commemorative plaque on Saturday 20 May. It won’t be on the site of the factory – still an industrialised area and not easily accessed. Instead it will be placed in a prominent position on a nearby housing estate, defiantly looking away from the factory towards Garratt Lane, the road along which the women marched on their way to Earlsfield Station and Trafalgar Square. Before they were irretrievably damaged by floods in 1968, this was the location of a cluster of terraced streets in which many of the factory workers lived. Thousands of people will pass the plaque every day on one of south London’s busiest roads.

Before the unveiling event I will be doing a guided walk of the area, visiting the factory location and passing the homes of many of the workers. Everyone is welcome and full details are here.

Geoff Simmons runs a community history project in south west London called Summerstown182, organising guided walks and talks, working with schools and putting up plaques that shine a light on some of the lesser-known history of the area.

Further reading

1. For Love and Shillings by Jo Stanley and Bronwen Griffiths, 1990, London History Workshop.

2. Righting the Wrong: Mary Macarthur 1880-1921. The working woman’s champion by Cathy Hunt, 2019, West Midlands History.

3. Visit the Summerstown182 blog.

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.