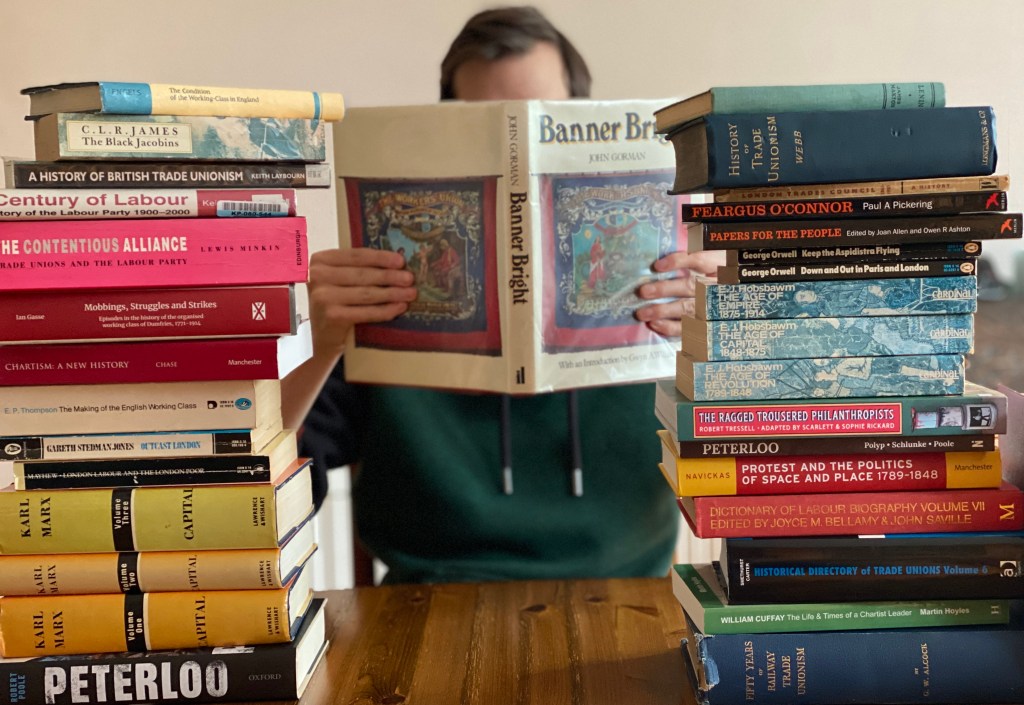

Newspapers and magazines always like to list their ‘best books of the year’ as Christmas approaches. But what if the best books weren’t published this year? Preferring to take a longer perspective, we asked labour historians to tell us about a work relevant to labour history that they felt was overlooked, should be better known – or which simply meant something to them. Here’s what they had to say…

- Mike Mecham on A.L. Morton’s A People’s History of England

- Keith Laybourn on Henry Pelling’s The Origins of the Labour Party 1880-1900

- Vic Clarke on Dorothy Thompson’s Outsiders: Class, Gender and Nation

- Angela V. John on Menna Gallie’s Strike for a Kingdom

- Quentin Outram on Karl Marx’s Capital: A Critique of Political Economy: Volume I: Capitalist Production

- Joe Stanley on John Rule’s The Experience of Labour in Eighteenth-Century Industry

- Peter Gurney on George Orwell’s Keep the Aspidistra Flying

- Keith Flett on Royden Harrison’s Before the Socialists

- Alan Campbell on Carter Goodrich’s The Miner’s Freedom

- Edda Nicolson on the Dictionary of Labour Biography

- Ralph Darlington on J.T. Murphy’s The Workers’ Committee: An Outline of Its Principles and Structure

- John McIlroy on Walter Kendall’s The Revolutionary Movement in Britain, 1900–1921

- Gregory Billam on Christopher Hill’s The World Turned Upside Down

- Mark Crail on British Labour Statistics: Historical Abstract 1886-1968

A People’s History of England, by A. L. Morton (1938 and 1965)

In his celebrated Labour in Irish History (1910) James Connolly challenged the notion that ‘…history has ever been written in the interests of the master class’. Nearly thirty years later (1938), another Marxist historian, A. L. Morton, picked up the mantle with his People’s History of England. While all Ireland recognises Connolly, few in England are aware of Morton; his History has received little critical attention from most other historians. Yet, It remains in print to this day, has been widely translated, and has spoken to and influenced many at home and abroad eg Zinn’s People’s History of the United States. Morton recounts English history through the lens of the masses who helped make and shape it. He emphasised that it was intended for the general reader and, with characteristic modesty, claimed ‘no pretence of being the result of original research’. Any value, he suggested, rested on his interpretation of the facts. Even today, his ‘general readers’ praise the clarity of its narrative and purpose, its ‘partisan flair’ as one put it, in exploring how economic relationships, particularly land ownership and property, and the relationship between classes, clash and bring about change. Dorothy Thompson said she cut her historical teeth on the book. While other prominent historians, such as Eric Hobsbawm and Christopher Hill, considered it the best general history available. It helped many of us to view history through those we came from.

Dr Mike Mecham is a Visiting Research Fellow at St Mary’s University, London, and is the author of William Walker: Belfast Labourist and Social Activist, 1870-1918

The Origins of the Labour Party 1880-1900, by Henry Pelling

Macmillan (1954)

This is one of those influential books which has sunk from sight in the study of the history of the Labour Party but which greatly influenced me. As a student of Jack Reynolds (a medieval and local historian) at the University of Bradford in the mid-1960s, I was taught about the emergence of the Labour Party and its origins. Although I was a member of the Labour Party at that time, I had never heard of the Social Democratic Federation, the Fabians, or the far more influential, Independent Labour Party. Jack suggested that I should read Henry Pelling’s book, which had just been reissued, and it became a revelation to me. It added flesh to the more buccaneering book by George Dangerfield, The Strange Death of Liberal England, written from the foothills of California, in the 1930s. Whist Dangerfield offered wringing phrases, referring to the 1906 General Election and establishing that the Liberal Party was ‘no longer the Left in British politics’, Pelling, in his best acerbic style, provided the evidence of trade union support for the early ILP and Labour Party. Indeed, he endorsed the idea that the Labour Party emerged because of the development of class politics, at a time when Trevor Wilson, The Downfall of the Liberal Party (1966), and others were suggesting that the emergence of the Labour Party was more to do with the Liberal Party being destroyed by the ‘accident of war’, the Great War. He established the importance of the Manningham Mills strike (1890-1891) in the formation of the ILP, the fact that St George’s Hall in Bradford, about three hundred yards away from where I was being taught, was effectively the birthplace of the ILP in January 1893, the body which became the intellectual godparent of the Labour Party. This all linked up with my reading on the 21st Conference of the ILP at St. George’s Hall, where J.H. Palin (a leader of the Amalgamated Railway Servants at the time of Taff Vale), I think, stated that of Bradford that,‘ Of ordinary historical association Bradford has none. In Domesday book it was described as a waste and successive periods of capitalist exploitation have done little to improve it. The history of Bradford will be very much the history of the ILP.’ Pelling’s work was later galvanised by Ross McKibbin’s book on The Evolution of the Labour Party (1974) and, indeed, David Howell, many others, and I have written on the ILP and the early Labour movement. Some of these texts are richer, more nuanced, and less matter of fact and acerbic than Pelling’s book. Nevertheless, in the 1960s it was a book which provided the necessary evidence for the debate on the rise of Labour and it certainly helped shape some of my later thinking and research.

Keith Laybourn is Diamond Jubilee Professor Emeritus at the University of Huddersfield and President of the Society for the Study of Labour History

Dorothy Thompson, Outsiders: Class, Gender and Nation

Verso (1993)

When I first fell into the rabbit hole of Chartist history, it was Dorothy Thompson’s historical essays which became foundational to my burgeoning understanding of the movement, its significance in the north of England, and its political legacies in the twentieth century and beyond. Thompson showed that class, gender, and personality were inextricably linked forces which drove both the successes and failures of the movement. Outsiders is an odd collection of essays, spanning Chartist historiography to Irish nationalism to, somewhat surprisingly for a communist, ‘Queen Victoria, the Monarchy, and Gender’. Reassuringly, Thompson compares (male) Chartist leaders and radical politicians with the Queen, whose gender was manipulated through the press to evoke a nurturing, domestic figure at the same time that Chartist women were portrayed as such.

‘Women and Nineteenth-Century Radical Politics’ offers an accessible yet detailed analysis of women’s public participation in the Chartist movement, but barely touches on its apparently sudden decline through the 1840s. Thompson merely notes that ‘Victorian sentimentalisation of the home and the family […] accepted with docility and obedience by the inferior members [of the family] became all-pervasive, and affected all classes.’ The ‘ending’ of this wave of politically active women seemed too sudden, too suspicious for me. It had to be a question of visibility, of working behind the scenes instead. My PhD supervisor, the late Malcolm Chase, reminded me to look at the original publication date of 1976; peak Women’s Liberation agitation. Remembering the context of historiography is a lesson I now pass onto my own students regularly.

Dr Vic Clarke is a Lecturer in Modern British Social History at Durham University, where she writes on the Chartist movement and nineteeenth century political activism

Strike for a Kingdom, by Menna Gallie

First published by Victor Gollancz (1959); Honno Press reprint, (2019) (Welsh Women’s Classics Series)

Set during the protracted miners’ lockout following the General Strike of May 1926, this is a gem of a novel by Menna Gallie (1919-90). Her grandfather had helped to found the Labour Representation Committee in South Wales and it’s a must for modern labour historians, historians of gender (it was praised by Eleanor Roosevelt), lovers of crime fiction (it was a runner-up for the Crime Writers’ Association’s Gold Dagger Award) and those who appreciate a witty and wise story-teller who draws upon her own experience of growing up in a Welsh mining community.

Angela V. John is a historian, biographer, a vice-president of SSLH and president of Llafur, the Welsh People’s History Society. She wrote the Introduction to the Honno reprint and knew Menna Gallie well

Capital: A Critique of Political Economy: Volume I: Capitalist Production, by Karl Marx

First German edition 1867, English translation by Ben Fowkes, Penguin Books (1976), reissued as a Penguin Classic (1990).

Marx has been given the reputation of a turgid writer and it’s true that the opening chapters of Capital are a bit dull. But they are also largely unnecessary. So skim rapidly through Parts I and II and go quickly to Part III. From here on in the plot develops slowly but the mood begins to vary from bright scorn to deep anger as Marx tells the story of the conflicts over the length of the working day in the first half of the nineteenth century. The story becomes gripping and Capital hard to put down. But this is not the only, or even the main, reason for reading Capital. Many historians, not least E. P. Thompson, have known how to move the reader with sympathy for the workers and disgust at the capitalists of the English industrial revolution. But in Part VII of Capital we start to see why capitalists behave the way they do. Capitalists must accumulate. ‘That is Moses and the Prophets!’ That means they must exploit their workers and workers and capitalists are set to fight each other. Marx understood what is often forgotten in labour history: that class conflict involves two classes (at least) and to understand the conflict we need to study both.

Quentin Outram is the Secretary of the Society for the Study of Labour History

The Experience of Labour in Eighteenth-Century Industry, by John Rule (1981)

This book is one of the most important contributions to labour history in the past fifty years because of Rule’s holistic approach to understanding how work, culture and protest were intimately connected throughout the eighteenth century. There are eight chapters in total. The first four cover the location of manufacturing and mining, the uncertainty and irregularity of work, the hours and wages of workers, the work and health of the labouring classes, and apprenticeship – including the use of parish apprentices. The final four chapters examine exploitation and embezzlement, the nature and extent of trade unionism, the effectiveness of trade unionism and industrial action, and, lastly, an analysis of the custom, culture and class-consciousness of the eighteenth-century worker. Rule uses a range of sources to investigate these themes, including government reports on the petitions of various trades such as journeymen calico printers, local and national newspapers, and early printed pamphlets such as Maton’s Observations on the Western Counties of England (1794-96) to demonstrate the continuity of the experience of labour. Rule argues that historians have overemphasised the significance of change in the eighteenth century and that ‘in the area of labour history much remained unchanged through the Industrial Revolution, and much even persisted long after it’. ‘The typical labour experience and response of the eighteenth century’, he added, ‘was not that of the factory proletariat’ because the factory system remained ‘in its infancy’ at the end of the century. Rule concludes that handworkers and artisans had ‘a formative role to play in the development of working-class consciousness’.

Joe Stanley is the Northern Schools Liaison Officer at Selwyn College, Cambridge and has published on eighteenth century protest in Yorkshire

Keep the Aspidistra Flying, by George Orwell (1936)

My choice for a Christmas read would be Orwell’s cynical, hard-headed novel about lower middle-class life in the thirties. While not a great novel, the work had a major impact on me when I started to read properly after I quit school, illustrating the point that a book does not have to be a classic in order to have influence. It tells the story of Gordon Comstock, who gives up a relatively well paid job as an advertising copywriter in order to become a ‘proper’ writer. He fails of course, eventually settling for respectable married life and an aspidistra in the window, like the rest of his class. What appealed to me as a teenager I think was not the thin plot but the main character’s denunciations of what he calls the ‘money god’. Every action, every relationship, every belief in the book is perceived by Comstock to be reducible to a monetary calculation, which appealed to an angry teenager. Orwell typically demonstrates a wilful refusal to think things through and his critique is limited. Nevertheless, the work is still well worth reading for its attack on the corrosive materialism of the ‘new consumerism’ of the time, especially at Christmas.

Peter Gurney is Professor of British Social History at the University of Essex and Editor of Labour History Review

Before the Socialists, by Royden Harrison (1965)

Royden Harrison’s book looks at what some might regard as one of the ‘unheroic’ periods of English labour history, between the final demise of Chartism and the rise of the new unions and independent labour political organisation.

It confines itself largely to the first of what might be seen as a two decade period – 1860 to 1880 –and looks at various aspects of working-class and radical activity and ideas in that period rather than trying to provide a comprehensive narrative.

Harrison’s analysis of working class attitudes to the US Civil War was ground breaking but remains a live issue almost 50 years on. His examination of the rise of organised labour – with the TUC founded in 1868 and the development of the Reform League, where working class and middle class radicals worked together for the vote – also broke new ground as did his emphasis on the Land and Labour League a proto-working class party.

There is heroism too though. While the Chartists protest for the vote on 10 April 1848 failed, the Reform League’s Hyde Park demonstration on 5 May 1867 succeeded. Many of the same activists were involved.

Keith Flett is Convenor of the London Socialist Historians Group

The Miner’s Freedom, by Carter Goodrich

Marshall Jones, Boston (1925); reprinted Arno Press, New York (1977)

Carter Lyman Goodrich (1897–1971), was an American labour economist best known for The Frontier of Control: A Study of British Workshop Politics (1920, republished 1975 by Pluto Press with a new Foreword by Richard Hyman), his classic study of demands for workers’ control based on research in Britain during a postgraduate fellowship in 1918. On his return to the United States, through his association with the Bureau of Industrial Research, he worked closely with the United Mine Workers. His analysis of working practices in US mines, based on extensive interviews with mine bosses, underground workers and union activists, is a more obscure publication than Frontier of Control but no less significant. Part 1 outlines the autonomy the faceworker enjoyed under traditional methods of mining: ‘The miner is an isolated piece worker, on a rough sort of craft work, who sees his boss less often than once a day’ (p. 41). Part 2 describes the threat to this freedom posed by ‘the new discipline’ associated with the spread of mechanised coal cutting. Part 3 concludes the analysis by noting that the new technology was still largely confined to weakly unionised coalfields, the threats to union organisation it posed, and the aspiration that ‘the older freedom’ be replaced by ‘the collective freedom of workers’ control’ (p.181).

I was alerted to Goodrich’s work when I commenced my doctoral research at the Centre for the Study of Social History at the University of Warwick (then a central hub in the newly burgeoning field of labour history) by my supervisor, Fred Reid. It proved seminal for our essay, ‘The Independent Collier in Scotland’ (in Royden Harrison, ed., Independent Collier: The Archetypal Proletarian Reconsidered, 1978). Goodrich’s statement, ‘The miner is his own boss’ (p. 15), echoed the observation of a Scottish miner in 1842: ‘The collier is his own master’. Central arguments of my monographs, The Lanarkshire Miners, 1775–1874 (1979) and The Scottish Miners, 1874–1939 (2000) were similarly indebted to the insights offered in The Miner’s Freedom. Goodrich went on to a distinguished academic career as a professor of economics at Colombia University. He maintained a lifelong sympathy for the labour movement as a consultant to the Department of Labor and chair of the governors of the ILO. After almost a century, his pioneering text remains an essential starting point for any historical analysis of the mining labour process.

Alan Campbell is a former editor of Labour History Review and was SSLH Chair, 2009–2011

Dictionary of Labour Biography

Volume I, Macmillan Press (1972), through to Volume XV (2019)

Okay, I’ll admit it. I know that I am cheating. I knew it would be too difficult to choose one book for this list, so I opted for a dictionary series instead. In my defence, I’m breaking the rules for good reason: the Dictionary of Labour Biography has been a constant friend for labour historians since the first 1972 edition, but is simply not given the credit it deserves.

Labour history is full of personality. The sheer grit and tenacity of the earliest activists from Tolpuddle and beyond has embedded what Malcolm Chase called ‘a thirst for life stories’ that has lasted for hundreds of years. Labour leaders continue to fascinate us; today, you’d struggle to find anyone that hasn’t heard of Mick Lynch and Sharon Graham. The DLB is a monument to this thirst for knowledge that labour historians have regarding the lives of trade unionists, politicians, and social reformers. True, the heavy lean towards white male figures in the earlier volumes is glaring, but the more recent editorial decisions show the DLB is now headed in the right direction.

The 15 volumes help us understand how the movement has been shaped by its leaders. It is always a pity that some entries can offer only scant details, but such is the constant frustration with searching for details on people from humble backgrounds. Nevertheless, politics and policies inevitably come from people, and knowing more about the everyday and formative experiences that shaped these people adds a simply beautiful richness to our understanding of the labour movement’s past and future.

Edda Nicolson is a Lecturer at the University of Wolverhampton, and researches twentieth century trade unionism

The Workers’ Committee: An Outline of Its Principles and Structure, by J.T. Murphy

London: Pluto Press (1972) [1917]

Since writing 25 years ago a political biography of J.T. Murphy, one of the remarkable leaders of the First World War National Shop Stewards’ and Workers’ Committee Movement, I’ve found myself repeatedly returning to his wonderful 1917 pamphlet.

Grounded on the practical experience of wartime engineering struggles and rise of the stewards’ movement, Murphy’s pamphlet went beyond the critique of trade union bureaucracy that had been made in the pre-war syndicalist-influenced The Miners’ Next Step to advance the theory of workplace-based independent rank-and-file organisation that operated both within and outside official union structures to counteract full-time officials’ influence. In the process it advocated the establishment of workshop committees (composed of shop stewards delegates) that represented all workers (irrespective of craft, grade or union) and linked to local Workers’ Committees (with aspirations to extend from engineering to the rest of industry) to create an all-encompassing class organisation on a national scale that would be capable of organising action independently of bureaucratic union officials if necessary when they were unresponsive to their members’ discontents.

The pamphlet represented a decisive advance on the strategies of pre-war syndicalism – which had either sought to replace existing unions with entirely new revolutionary industrial ones, or reconstruct them through their amalgamation into industrial unions with revolutionary objectives. By fusing both elements into a novel synthesis it encouraged a rank-and-file movement that could walk on two legs, official and unofficial. And influenced by the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, it pointed to how the Workers’ Committees (rather than either industrial unions or a parliamentary political party) could ultimately become a revolutionary weapon for the overthrow of capitalism and its replacement by workers’ control of society.

It’s true there were important disparities between the principles outlined and the actual practice of the Shop Stewards’ and Workers’ Committee Movement, and the pamphlet completely failed to link workers’ economic struggles to the war and the important political issues that were raised. Nonetheless, arguably its pioneering attempt to devise means of counteracting the influence of union officialdom, as well as its identification of the chief agency of working-class power and socialism, remain of enduring historical significance and contemporary relevance.

Ralph Darlington is Emeritus Professor of Employment Relations at the University of Salford and author of The Political Trajectory of J.T. Murphy (1998), Radical Unionism (2013) and the forthcoming Labour Revolt in Britain 1910-14 (2023)

The Revolutionary Movement in Britain, 1900–1921, by Walter Kendall

Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London (1969)

Walter Kendall (1926–2003) was a libertarian Marxist, active in the Shopworkers’ Union and the Labour Party left. A leading light in the Institute for Workers’ Control, founding editor of Voice of the Unions, and prominent in the Polish Solidarity Campaign, he was a socialist scholar who succeeded Eric Hobsbawm as chair of this Society. Kendall was a tireless crusader against what he held to be the mutually reinforcing evils of capitalist exploitation and Stalinist oppression. His best-known work, The Revolutionary Movement in Britain was animated by an abiding preoccupation with the debilitating division between Social Democracy and Communism engendered by the creation of the Comintern and sealed domestically by the formation of the British Communist Party (CPGB). Understanding its roots was, he believed, necessary to remedying it and replacing two ideologies antagonistic to the interests of the working class with a transformative and democratic socialism.

Part 1 of the book explores the forces, actors and contexts which combined to accomplish the historic split. It focusses on the CPGB’s main precursors, the Social Democratic Federation/ Social Democratic Party/British Socialist Party and the smaller Socialist Labour Party – although developments in the ILP, the Labour Party and the trade unions are not neglected. Kendall traces the evolution of the revolutionary organisations away from the sectarian nationalism of H.M. Hyndman and the dogmatic, industrial unionist ideas of Daniel DeLeon under the impact of the industrial militancy of ‘the Great Unrest’, ‘the Great War’, and the Bolshevik revolution. Innovative essays examine then under-researched topics, the emergence of the shop stewards’ movement and the global circulation of revolutionary ideas and cadres embodied in the Russian diaspora. Teleology rarely intrudes on histories anchored in the contemporary and the contingent which are always alert to international developments.

The spotlight turns in Part 2 to the post-war conjuncture across Europe and the processes which culminated in the creation of British Communism. The canvas is extended to address the ILP left, the Guild Socialists, the Labour Research Department, movements around John Maclean in Scotland and other bodies which contributed to the making of the CPGB. Kendall crowned a work brimming with fresh insights with a tour de force of pioneering research detailing the part played by the Comintern backed by the financial resources of the Soviet state. Integrating and going beyond earlier work such as Pribićević (on the shop stewards), Tsuzuki (on Hyndman) and Pelling and Macfarlane (on Communism), his monograph stands in the best traditions of analytical-narrative political history. As A.J.P. Taylor concluded, reviewing the book in the Observer, ‘it makes a wonderful story’.

Kendall’s arguments and counterfactuals proved more controversial. The view that without Comintern intervention the CPGB would not have taken the form it did is compelling; it is putting things too strongly to characterise the party as ‘an artificial creation’. Despite its significance, Russian agency would not have proved decisive without the support of most British revolutionaries: they identified with 1917 and voluntarily willed a united Communist Party on Bolshevik lines as the best available answer to their problems. The suggestion that a ‘continuation BSP’ in the throes of regeneration constituted a viable alternative to the CPGB is imprecise and under-evidenced. If we consider its inability to register substantial progress in its goals of eroding the hegemony of reformism and implanting a significant revolutionary current in the working class, then Kendall’s judgment, looking back from 1969, that the CPGB was a failure is convincing. Hindsight is helpful in understanding what went wrong in the past. But the party was not doomed at birth. The manner of its nativity influenced its later life; it did not determine it. The course it took depended on the choices Communists made in succeeding years.

Since 1969, an ever-expanding volume of research has enriched our knowledge of labour and the left in the early twentieth century. The Revolutionary Movement remains an indispensable part of the historiography. I would recommend it to all those seeking to understand this important and exciting period.

John McIlroy is a former secretary of the Society for the Study of Labour History

The World Turned Upside Down, by Christopher Hill (1972)

My choice for a Christmas read would be Christopher Hill’s ground-breaking study of the radical ideas and movements which underpinned the English Revolution – or at least the revolution that ‘at times threatened, but never was’. The World Turned Upside Down was first published fifty years ago and remains a key text in the area twenty years after Hill’s death. Hill brings to light the submerged and often highly ridiculed groups whom society has tended to regard as extremists and cultists. The Levellers, Diggers, Ranters, as well as other religious groups are placed at the forefront of a period, which in Hill’s words, ‘literally anything seemed possible’.

Bryan Palmer wrote, at the turn of the century, regarding the Communist Party Historians Group – of which Hill was a member – that ‘we do not so much as stand on the shoulders of these historians…as we occupy their shadows’. Re-reading this book has reiterated to me how much we owe to this group of historians. The study of everyday common people, not of the affairs of Kings and Queens, aided the movement towards ‘histories from below’, which Hill exemplified, prompting a sea-change in how everyday people were understood. ‘It is no longer necessary’, he noted, ‘to apologise too profusely for taking the common people of the past on their own terms and trying to understand them’. There is little doubt that the book holds up well fifty years later. Its prose and command of argument is delivered with Hill’s characteristic flair. The World Turned Upside Down is probably the most exciting of Hill’s works, and one I will return to again and again. It is a true classic in labour history.

Gregory Billam is a PhD candidate and Graduate Teaching Assistant in History at Edge Hill University

British Labour Statistics: Historical Abstract 1886-1968

Department of Employment and Productivity (1971)

The British government first began to collect and publish labour statistics in any organised way in the mid-1880s, when at the urging of the Liberal MP Charles Bradlaugh the Board of Trade recruited the engineering union leader John Burnett as labour correspondent. After which time a steady stream of raw data began to flow into Whitehall, enabling the prolific Burnett and his successors to create actionable information on everything from trade union organisation to the number of hours worked and rates of pay in various trades, the numbers killed in industrial accidents, and the number of stoppages and strike days. In British Labour Statistics, the then Department of Employment and Productivity brought together an abstract of the most important data collected over the best part of a century, as a precursor and planned starting point for a future planned yearbook, publication of which was set to begin in 1969. This might seem an odd choice of book to include in a selection of this sort – a volume suffering, as the old joke about the Telephone Directory has it, from a definite lack of character development or plot. But the statistics as they pile up year by year, showing the rise and fall of industries, fluctuations in wages, and the century-long fall in workplace deaths, tell a million stories populated by the tens of millions of men and women whose experiences are captured in these data tables.

Mark Crail is web editor for the Society for the Study of Labour History

Discover more from Society for the Study of Labour History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.